أبو سمبل

( Abu Simbel )

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel (Arabic: أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is located on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about 230 km (140 mi) southwest of Aswan (about 300 km (190 mi) by road). The twin temples were originally carved out of the mountainside in the 13th century BC, during the 19th Dynasty reign of the Pharaoh Ramesses II. Their huge external rock relief figures of Ramesses II have become iconic. His wife, Nefertari, and children can be seen in smaller figures by his feet. Sculptures inside the Great Temple commemorate Ramesses II's heroic leadership at the Battle of Kadesh.

The complex was relocated in its entirety in 1968 to higher ground to avoid it being submerged by Lake Nasser, the Aswan Dam reservoir. As part of International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, an artifici...Read more

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel (Arabic: أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is located on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about 230 km (140 mi) southwest of Aswan (about 300 km (190 mi) by road). The twin temples were originally carved out of the mountainside in the 13th century BC, during the 19th Dynasty reign of the Pharaoh Ramesses II. Their huge external rock relief figures of Ramesses II have become iconic. His wife, Nefertari, and children can be seen in smaller figures by his feet. Sculptures inside the Great Temple commemorate Ramesses II's heroic leadership at the Battle of Kadesh.

The complex was relocated in its entirety in 1968 to higher ground to avoid it being submerged by Lake Nasser, the Aswan Dam reservoir. As part of International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, an artificial hill was made from a domed structure to house the Abu Simbel Temples, under the supervision of a Polish archaeologist, Kazimierz Michałowski, from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw.

The Abu Simbel complex, and other relocated temples from Nubian sites such as Philae, Amada, Wadi es-Sebua, are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the Nubian Monuments.

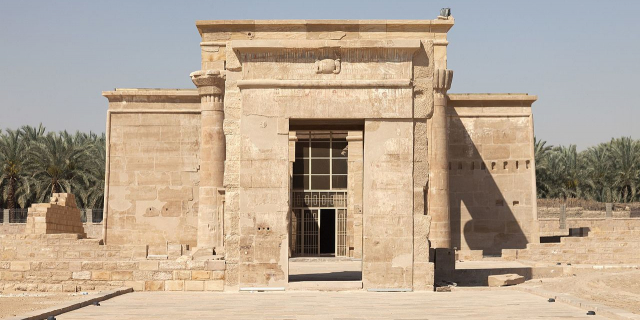

During his reign, Ramesses II embarked on an extensive building program throughout Egypt and Nubia, which Egypt controlled. Nubia was very important to the Egyptians because it was a source of gold and many other precious trade goods. He, therefore, built several grand temples there in order to impress upon the Nubians Egypt's might and Egyptianize the people of Nubia.[1][2] The most prominent temples are the rock-cut temples near the modern village of Abu Simbel, at the Second Nile Cataract, the border between Lower Nubia and Upper Nubia.[2] There are two temples, the Great Temple, dedicated to Ramesses II himself, and the Small Temple, dedicated to his chief wife Queen Nefertari.

Construction of the temple complex started in c. 1264 BC and lasted for about 20 years, until 1244 BC.[citation needed] It was known as the Temple of Ramesses, Beloved by Amun.

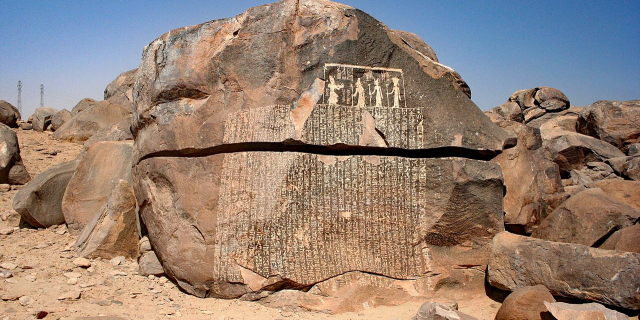

Rediscovery 1840s sketch from The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia showing how the sand had partially covered the great temple. Note this was approximately two decades after Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni had removed some of the sand in order to create an entrance to the Great Temple

1840s sketch from The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia showing how the sand had partially covered the great temple. Note this was approximately two decades after Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni had removed some of the sand in order to create an entrance to the Great TempleWith the passage of time, the temples fell into disuse and the Great Temple eventually became mostly covered by a sand dune. By the 6th century BC, the sand already covered the statues of the main temple up to their knees.[citation needed] The temple was forgotten by Europeans until March 1813, when the Swiss researcher Johann Ludwig Burckhardt found the small temple and top frieze of the main temple.

When we reached the top of the mountain, I left my guide, with the camels, and descended an almost perpendicular cleft, choaked with sand, to view the temple of Ebsambal, of which I had heard many magnificent descriptions. There is no road at present to this temple... It stands about twenty feet above the surface of the water, entirely cut out of the almost perpendicular rocky side of the mountain, and in complete preservation. In front of the entrance are six erect colossal figures, representing juvenile persons, three on each side, placed in narrow recesses, and looking towards the river; they are all of the same size, stand with one foot before the other, and are accompanied by smaller figures... Having, as I supposed, seen all the antiquities of Ebsambal, I was about to ascend the sandy side of the mountain by the same way I had descended; when having luckily turned more to the southward, I fell in with what is yet visible of four immense colossal statues cut out of the rock, at a distance of about two hundred yards from the temple; they stand in a deep recess, excavated in the mountain; but it is greatly to be regretted, that they are now almost entirely buried beneath the sands, which are blown down here in torrents. The entire head, and part of the breast and arms of one of the statues are yet above the surface; of the one next to it scarcely any part is visible, the head being broken off, and the body covered with sand to above the shoulders; of the other two, the bonnets only appear. It is difficult to determine, whether these statues are in a sitting or standing posture; their backs adhere to a portion of rock, which projects from the main body, and which may represent a part of a chair, or may be merely a column for support.[3]

Burckhardt talked about his discovery with the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni, who travelled to the site, but was unable to dig out an entry to the temple. Belzoni returned in 1817, this time succeeding in his attempt to enter the complex. A detailed early description of the temples, together with contemporaneous line drawings, can be found in Edward William Lane's Description of Egypt (1825–1828).[4]

Relocation The statue of Ramses the Great at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel is reassembled after having been moved in 1967 to save it from flooding.

The statue of Ramses the Great at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel is reassembled after having been moved in 1967 to save it from flooding.In 1959, an international donations campaign to save the monuments of Nubia began: the southernmost relics of this ancient civilization were under threat from the rising waters of the Nile that were about to result from the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

A scale model showing the original and current location of the temple (with respect to the water level) at the Nubian Museum, in Aswan.

A scale model showing the original and current location of the temple (with respect to the water level) at the Nubian Museum, in Aswan.One scheme to save the temples was based on an idea by William MacQuitty to build a clear freshwater dam around the temples, with the water inside kept at the same height as the Nile. There were to be underwater viewing chambers. In 1962 the idea was made into a proposal by architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry and civil engineer Ove Arup.[5] They considered that raising the temples ignored the effect of erosion of the sandstone by desert winds. However, the proposal, though acknowledged to be extremely elegant, was rejected.[citation needed]

The salvage of the Abu Simbel temples began in 1964 by a multinational team of archeologists, engineers and skilled heavy equipment operators working together under the UNESCO banner; it cost some $40 million (equivalent to $377.42 million in 2022). Between 1964 and 1968, the entire site was carefully cut into large blocks (up to 30 tons, averaging 20 tons), dismantled, lifted and reassembled in a new location 65 metres higher and 200 metres back from the river, in one of the greatest challenges of archaeological engineering in history.[6] Some structures were even saved from under the waters of Lake Nasser. Today, a few hundred tourists visit the temples daily. Most visitors arrive by road from Aswan, the nearest city. Others arrive by plane at Abu Simbel Airport, an airfield specially constructed for the temple complex whose sole destination is Aswan International Airport.

The complex consists of two temples. The larger one is dedicated to Ra-Horakhty, Ptah and Amun, Egypt's three state deities of the time, and features four large statues of Ramesses II in the facade. The smaller temple is dedicated to the goddess Hathor, personified by Nefertari, Ramesses's most beloved of his many wives.[7] The temple is now open to the public.

Add new comment