Alcázar de Segovia

( Alcázar of Segovia )

The Alcazar of Segovia is a medieval castle located in the city of Segovia, in Castile and León, Spain. It has existed since at least the 12th century, and is one of the most renowned medieval castles globally and one of the most visited landmarks in Spain. It has been the backdrop for significant historical events and has been home to twenty-two kings, along with notable historical figures.

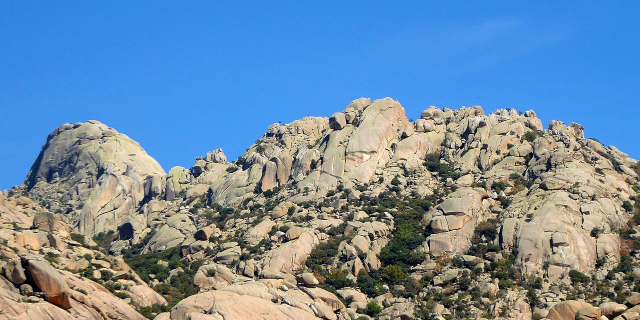

The fortress stands on a rocky crag at the western end of Segovia's Old City, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, above the confluence of rivers Eresma and Clamores. Today, it is used as a museum and a military archives building since its declaration as a National Archive by a Royal Decree in 1998. It has also worked at times as a state prison, a Royal Artillery College, and a military academy.

The Alcazar served both as a royal palace and a fortress for the Castilian monarchs, and its architecture reflects the grandeur and...Read more

The Alcazar of Segovia is a medieval castle located in the city of Segovia, in Castile and León, Spain. It has existed since at least the 12th century, and is one of the most renowned medieval castles globally and one of the most visited landmarks in Spain. It has been the backdrop for significant historical events and has been home to twenty-two kings, along with notable historical figures.

The fortress stands on a rocky crag at the western end of Segovia's Old City, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, above the confluence of rivers Eresma and Clamores. Today, it is used as a museum and a military archives building since its declaration as a National Archive by a Royal Decree in 1998. It has also worked at times as a state prison, a Royal Artillery College, and a military academy.

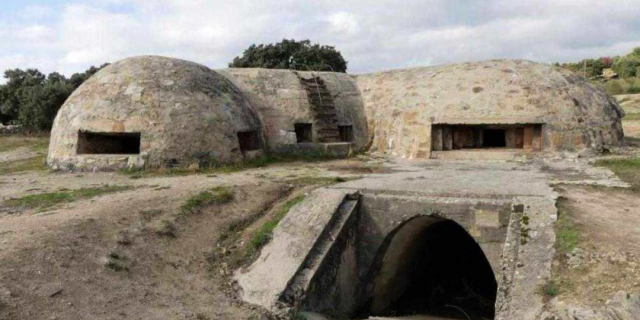

The Alcazar served both as a royal palace and a fortress for the Castilian monarchs, and its architecture reflects the grandeur and is a notable example of "power architecture": the impenetrable walls, the deep moat, its impressive towers like the Homage or Juan II's, and the strategic location symbolize power and authority. Furthermore, the luxury and opulence of its interior, with lavishly decorated rooms and coffered ceilings, were designed to awe and subdue visitors, reinforcing the authority of the Kings of Castile. Similarly, the legends and rumors surrounding the Alcazar of Segovia have played a significant role in its history.

Despite its stern and fortified appearance, the Alcazar of Segovia has also been a place of daily life. Many princes, nobles, and infants have grown up within its halls, and their presence has helped soften the palace's appearance, making the castle a home for many.

Its history begins in the 12th or early 13th century when the royal family of Castile had quarters in the Alcazar, known as the "major palace". In the Homage tower, the treasure of the Crown of Castile was stored, from which funds were secured to finance Christopher Columbus's first voyage. In 1437, the books of the royal administration were moved to the Alcazar, establishing one of the first royal archives of Castile and laying one of the foundations for the current General Archive of Simancas. Additionally, the Alcazar housed the royal armory, which served as the basis for the one now exhibited in the Royal Armory of Madrid.

The Alcazar has been the stage for crucial events in Spain's history, such as the Cortes of Castile, held there on multiple occasions; the signing of the Concord of Segovia, which laid the groundwork for the formation of the Spanish nation, took place there; Isabel the Catholic, one of the most significant and influential women in history, left the Alcazar to proclaim herself queen of Castile. It was also the site of the last meeting between Christopher Columbus and King Ferdinand the Catholic before the explorer's death. The marriage of Philip II to Ana of Austria strengthened the alliance between the House of Habsburg and the Hispanic Monarchy. As the headquarters of the royal college of artillery, in the 18th century, the first military flight for military purposes was carried out, marking the beginning of military aviation, and the chemist Louis Proust, a professor at the Royal College, formulated the Law of Definite Proportions, a fundamental advance in modern chemistry.

The Alcazar of Segovia has made its mark on cinema and popular culture. It was used by Orson Welles in the film "Chimes at Midnight" and served as inspiration for Cinderella castle in the Walt Disney movie.

Tower of John II of Castile

Tower of John II of Castile Painting of the Alcázar of Segovia, circa 1838 by David Roberts

Painting of the Alcázar of Segovia, circa 1838 by David RobertsThe Alcázar of Segovia, like many fortifications in Spain, started off as a Roman castrum,[1] but apart from the foundations, little of the original structure remains.[2] The alcázar was built by the Berber Almoravid dynasty. Almoravid art and architecture is scarcely talked about in scholarship in part because so little of the physical work has survived in Spain.[3] Furthermore, the Almoravid dynasty was short-lived and therefore much of the art and architecture of that period was subsequently destroyed or converted by their successors.

The first reference to this castle was in 1120, around 32 years after the city of Segovia was conquered by the Christians (during the Reconquista when King Alfonso VI reconquered lands to the south of the Duero river, down to Toledo and beyond).[4] In 1258, during the reign of King Alfonso X of Castile (r. 1252–1284), an intense thunderstorm caused a fire that destroyed several rooms, leading to centuries-long reconstruction during the reigns of various kings.[4]

It is not known what the shape and form of the Alcázar was before the reign of King Alfonso VIII (1155–1214), however early documentation mentioned a wooden stockade fence.[citation needed] It can be concluded[by whom?] that prior to Alfonso VIII's reign, the Muslim era structure was no more than a wooden fort built over the old Roman foundations. Alfonso VIII and his wife, Eleanor of England (sister of Richard the Lionheart), made this alcázar their principal residence and much work was carried out to erect the beginnings of the stone fortification we see today.[citation needed]

The Alcázar of Segovia was one of the favorite royal residences starting in the 13th century that in turn, led to secular patronage to the city of Segovia.[5] It was during this period that most of the current building was constructed by the House of Trastámara.[4]

In 1258, parts of the Alcázar had to be rebuilt by King Alfonso X after a cave-in and the Hall of Kings was built to house Parliament soon after.[citation needed] However, the single largest contributor to the continuing construction of the Alcázar was King John II of Castile who built the "New Tower" (John II tower as it is known today).[citation needed]

In 1474, the Alcázar played a major role in the rise of Queen Isabella I. On 12 December news of King Henry IV's death in Madrid reached Segovia and Isabella immediately took refuge within the walls of the Alcázar where she received the support of Andres Cabrera and Segovia's council.[citation needed] She was enthroned the next day as Queen of Castile and León.

The next major renovation at the Alcázar was conducted by King Philip II after his marriage to Anna of Austria.[citation needed] He added the sharp slate spires to reflect the castles of central Europe.[citation needed] In 1587, architect Francisco de Mora completed the main garden and the School of Honor areas of the castle.[citation needed]

During his visit to Spain known as the "Spanish match", Prince Charles of England visited the Alcázar in 1623, after dining at Valsain.[6] He was entertained by Luis Jerónimo de Cabrera, 4th Count of Chinchón, who was then keeper of the Alcázar. Prince Charles was shown the Galley Room or "second great hall" with the heraldry of Catherine of Lancaster. In the evening there was a torchlit masque involving 32 mounted knights. Prince Charles gave the Count of Chinchón a jewel and rewarded the poet Don Juan de Torres for his verses. He left early in the morning for Santa María la Real de Nieva.[7]

The restoration of the Royal College of Artillery was among the many reforms conducted under the reign of King Charles III of Spain (r. 1759–1788). He appointed Count Félix Gazzola as the director of the artillery corps, who made the executive decision to install the academy in the Segovian fortress in the Alcázar. At its opening in 1764, the military college stood as a symbol of the city's new age of progress in political and military education.[4]

On 6 March 1862, another fire occurred at the castle, destroying the sumptuous ceilings of the private rooms that were reserved exclusively for the nobility. As demonstrated in the engravings by José María Avrial and Flores in 1839, the structures were restored to their previous appearances.[8][9][10]

Etching of the Alcázar of Segovia ( c. 1842) by José María Avrial y Flores

Etching of the Alcázar of Segovia ( c. 1842) by José María Avrial y FloresIn 1896, King Alfonso XIII ordered the Alcázar to be handed over to the Ministry of War as a military college.[citation needed]

The Board of Trustees of the Alcázar of Segovia was created by the Decree of the Presidency of the Government, on 18 January 1951. The purpose of this was to ensure cultural, artistic, and historical preservation of the Alcázar's triple function as a royal castle, military precinct, and military academy.[4]

The Belt Room

The Belt Room

Add new comment