Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park is an American national park located in western Colorado and managed by the National Park Service. There are two primary entrances to the park: the south rim entrance is located 15 miles (24 km) east of Montrose, while the north rim entrance is 11 miles (18 km) south of Crawford and is closed in the winter. The park contains 12 miles (19 km) of the 48-mile-long (77 km) Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. The national park itself contains the deepest and most dramatic section of the canyon, but the canyon continues upstream into Curecanti National Recreation Area and downstream into Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area. The canyon's name owes itself to the fact that parts of the gorge only receive 33 minutes of sunlight a day, according to Images of America: The Black Canyon of the Gunnison. In the book, author Duane Vandenbusche states, "Several canyons of the American West are longer and some are deeper, but none combine...Read more

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park is an American national park located in western Colorado and managed by the National Park Service. There are two primary entrances to the park: the south rim entrance is located 15 miles (24 km) east of Montrose, while the north rim entrance is 11 miles (18 km) south of Crawford and is closed in the winter. The park contains 12 miles (19 km) of the 48-mile-long (77 km) Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. The national park itself contains the deepest and most dramatic section of the canyon, but the canyon continues upstream into Curecanti National Recreation Area and downstream into Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area. The canyon's name owes itself to the fact that parts of the gorge only receive 33 minutes of sunlight a day, according to Images of America: The Black Canyon of the Gunnison. In the book, author Duane Vandenbusche states, "Several canyons of the American West are longer and some are deeper, but none combines the depth, sheerness, narrowness, darkness, and dread of the Black Canyon."

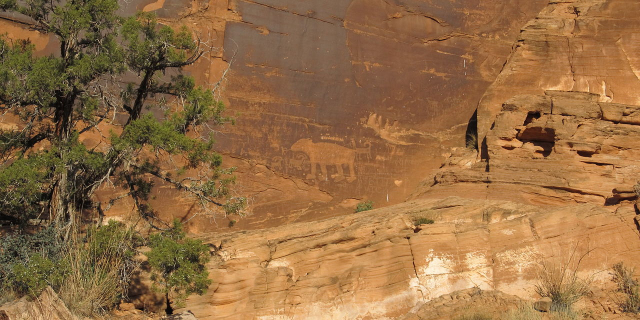

The Ute had known the canyon to exist for a long time before the first Europeans saw it. They referred to the river as "much rocks, big water," and are known to have avoided the canyon out of superstition.[1] By the time the United States declared independence in 1776, two Spanish expeditions had passed by the canyons. In the 1800s, the numerous fur trappers searching for beaver pelts would have known of the canyon's existence but they left no written record. The first official account of the Black Canyon was provided by Captain John Williams Gunnison in 1853, who was leading an expedition to survey a route from Saint Louis and San Francisco. He described the country to be "the roughest, most hilly and most cut up," he had ever seen, and skirted the canyon south towards present-day Montrose. Following his death at the hands of the Ute later that year, the river that Captain Gunnison had called the Grand was renamed in his honor.[2]

The Denver & Rio GrandeIn 1881, William Jackson Palmer's Denver and Rio Grande Railroad had reached Gunnison from Denver. The line was built to provide a link to the burgeoning gold and silver mines of the San Juan mountains. The rugged terrain precluded using 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1.435 m) standard rail; Palmer decided to go with the narrower 3 ft (0.91 m) gauge. It took over a year for Irish and Italian laborers to carve out a 15-mile (24 km) roadbed from Sapinero to Cimarron, costing a staggering $165,000 per mile. The last mile is said to have cost more than the entire Royal Gorge project.[3]

On August 13, 1882, the first passenger train passed through the Black Canyon. The editor of the Gunnison Review-Press rode in one of the observation cars; he remarked that the canyon was "undoubtedly the largest and most rugged canyon in the world traversed by the iron horse. We had often heard of the scenery of this canyon, but no one can have the faintest conception of its grandeur and magnificence until they have made a trip through it. It is a narrow gorge with walls of granite rising in some places to a height of thousands of feet ... Throughout its entire length there is probably not a quarter of a mile of straight track on it. It is a serpentine road in every respect and the curves are frequent and sharp. In hundreds of places the walls of granite are perpendicular and in many places the road bed is blasted out in the side of the walls of rock which overhang the track." He went on to proclaim, "Another such a feat of railroad engineering probably can not be found in the world, and there is probably no section of Colorado or of the whole country where such a varied and interesting lot of scenery can be found."[4]

Preserved rail bridge over Cimarron Creek

Preserved rail bridge over Cimarron CreekIn the hopes of running the railroad through the rest of the Black Canyon, Palmer sent his top engineer Bryan Bryant on an inner canyon exploration. Bryant set off with a 12-man crew in December 1882 expecting to complete the survey in 20 days; he returned in 68. "Eight of the twelve-man crew left after a few days, terrified of the task in front of them. What the rest of the men saw was spectacular and had never been seen by another human." Bryant reported that the Black Canyon was impenetrable, and that it was impossible to build anything in its depths.[5]

Heeding Bryant's advice, Palmer decided to route the railroad south of the canyon and in March 1883, it completed its connection to Salt Lake City and for a brief period the canyon was on the main line of a transcontinental railroad system. While the railroad and early visitors used the canyon as a path to Utah and mines to the southwest, later visitors came to see the canyon as an opportunity for recreation and personal enjoyment.[6]Rudyard Kipling described his 1889 ride through the canyon in the following words: "We entered a gorge, remote from the sun, where the rocks were two thousand feet sheer, and where a rock splintered river roared and howled ten feet below a track which seemed to have been built on the simple principle of dropping miscellaneous dirt into the river and pinning a few rails a-top. There was a glory and a wonder and a mystery about the mad ride..."[7]

By 1890, an alternate route through Glenwood Springs had been completed and the route through the Black Canyon, being more difficult to operate, lost importance for through trains. However, local rail traffic continued over the "Black Canyon Line" until the route was finally abandoned in the early 1950s.[8][9] Today, various elements of the railroad have been preserved in the Cimarron area including a steel bridge in Cimarron Canyon.[10]

The Gunnison TunnelIn 1901, the U.S. Geological Survey sent Abraham Lincoln Fellows and William Torrence into the canyon to look for a site to build a diversion tunnel bringing water to the Uncompahgre Valley, which was suffering from water shortages due to an influx of settlers into the area.[11] Torrence, a Montrose native and an expert mountaineer, joined four other men in a failed expedition to explore the canyon in September 1900 using two wooden boats. His experience proved invaluable on the second attempt in August 1901. Torrence and Fellows opted to bring a small specially made multi-chambered rubber raft with a lifeline all the way around it instead of the wooden boats that had doomed the previous journey. The two men entered the canyon on August 12 equipped with "hunting knives, two silk lifeline ropes, and rubber bags to encase their instruments." Torrence and Fellows each had backpacks weighing 35 pounds and the rubber raft turned out to be a great way to float their gear on the narrow river. After 10 days of climbing over rock falls, descending waterfalls, and swimming over 70 sections of the river, they emerged from their 30 mile run with a first recorded descent as well as a suitable tunnel site.[12][13][14][15][16]

Construction on the tunnel began 4 years later, and was fraught with difficulties right from the onset. "Working conditions at the tunnel were difficult due to the high levels of carbon dioxide, excessive temperatures, humidity, water, mud, shale, sand, and a fractured fault zone...It took the tunneling crew almost one year to bore through 2000 feet of water-filled rock. The tunnel was driven through granite, quartzite, gneiss, and shale as well as layers of sandstone, coal, and limestone. Work on the Gunnison Tunnel was first done manually and by candlelight. One miner would hold the drill and rotate it while the second miner would use a sledgehammer to drive the drill into the rock. This work required strong, hard-working men. In spite of good pay and fringe benefits, most disliked the dangerous underground conditions and stayed an average of only 2 weeks." 26 men were killed during the 4 year undertaking. The tunnel was finally completed in 1909, stretching a distance of 5.8 miles and costing nearly 3 million dollars. At the time, the Gunnison Tunnel held the honor of being the world's longest irrigation tunnel. On September 23, President William Howard Taft dedicated the tunnel in Montrose.[17] The East Portal of the Gunnison Tunnel is accessible via East Portal Road which is on the South Rim of the canyon. Although the tunnel itself is not visible, the diversion dam can be seen from the campground.[18]

Creation of the park Park Headquarters, South Rim

Park Headquarters, South RimThe Black Canyon of the Gunnison was established as a national monument on March 2, 1933, and was redesignated a national park on October 21, 1999.[19] During 1933-35, the Civilian Conservation Corps built the North Rim Road to design by the National Park Service. This includes five miles of roadway and five overlooks; it is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as a historic district.[20]

About half of the park, 15,599 acres (63.13 km2), was designated a wilderness area in 1976.[21]

Add new comment