Context of Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called Tawantinsuyu by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts") was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilization arose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. The Spanish began the conquest of the Inca Empire in 1532 and by 1572, the last Inca state was fully conquered.

From 1438 to 1533, the Incas incorporated a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean Mountains, using conquest and peaceful assimilation, among other methods. At its largest, the empire joined modern-day Peru, what are now western Ecuador, western and south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, the southwesternmost tip of Colombia and a large portion of mod...Read more

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called Tawantinsuyu by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts") was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilization arose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. The Spanish began the conquest of the Inca Empire in 1532 and by 1572, the last Inca state was fully conquered.

From 1438 to 1533, the Incas incorporated a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean Mountains, using conquest and peaceful assimilation, among other methods. At its largest, the empire joined modern-day Peru, what are now western Ecuador, western and south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, the southwesternmost tip of Colombia and a large portion of modern-day Chile into a state comparable to the historical empires of Eurasia. Its official language was Quechua.

The Inca Empire was unique in that it lacked many of the features associated with civilization in the Old World. Anthropologist Gordon McEwan wrote that the Incas were able to construct "one of the greatest imperial states in human history" without the use of the wheel, draft animals, knowledge of iron or steel, or even a system of writing. Notable features of the Inca Empire included its monumental architecture, especially stonework, extensive road network reaching all corners of the empire, finely-woven textiles, use of knotted strings (quipu) for record keeping and communication, agricultural innovations and production in a difficult environment, and the organization and management fostered or imposed on its people and their labor.

The Inca Empire functioned largely without money and without markets. Instead, exchange of goods and services was based on reciprocity between individuals and among individuals, groups, and Inca rulers. "Taxes" consisted of a labour obligation of a person to the Empire. The Inca rulers (who theoretically owned all the means of production) reciprocated by granting access to land and goods and providing food and drink in celebratory feasts for their subjects.

Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred Huacas, but the Inca leadership encouraged the sun worship of Inti – their sun god – and imposed its sovereignty above other cults such as that of Pachamama. The Incas considered their king, the Sapa Inca, to be the "son of the sun".

The Incan economy is a subject of scholarly debate. Darrell E. La Lone, in his work The Inca as a Nonmarket Economy, noted that scholars have described it as "feudal, slave, [or] socialist," as well as "a system based on reciprocity and redistribution; a system with markets and commerce; or an Asiatic mode of production."

More about Inca Empire

- Antecedents

The Inca Empire was the last chapter of thousands of years of Andean civilizations. The Andean civilization is one of at least five civilizations in the world deemed by scholars to be "pristine." The concept of a "pristine" civilization refers to a civilization that has developed independently from external influences and is not a derivative of other civilizations.[1]

The Inca Empire was preceded by two large-scale empires in the Andes: the Tiwanaku (c. 300–1100 AD), based around Lake Titicaca, and the Wari or Huari (c. 600–1100 AD), centered near the city of Ayacucho. The Wari occupied the Cuzco area for about 400 years. Thus, many of the characteristics of the Inca Empire derived from earlier multi-ethnic and expansive Andean cultures.[2] To those earlier civilizations may be owed some of the accomplishments cited for the Inca Empire: "thousands of miles of roads and dozens of large administrative centers with elaborate stone construction...terraced mountainsides and filled in valleys", and the production of "vast quantities of goods".[3]

...Read moreAntecedentsRead lessThe Inca Empire was the last chapter of thousands of years of Andean civilizations. The Andean civilization is one of at least five civilizations in the world deemed by scholars to be "pristine." The concept of a "pristine" civilization refers to a civilization that has developed independently from external influences and is not a derivative of other civilizations.[1]

The Inca Empire was preceded by two large-scale empires in the Andes: the Tiwanaku (c. 300–1100 AD), based around Lake Titicaca, and the Wari or Huari (c. 600–1100 AD), centered near the city of Ayacucho. The Wari occupied the Cuzco area for about 400 years. Thus, many of the characteristics of the Inca Empire derived from earlier multi-ethnic and expansive Andean cultures.[2] To those earlier civilizations may be owed some of the accomplishments cited for the Inca Empire: "thousands of miles of roads and dozens of large administrative centers with elaborate stone construction...terraced mountainsides and filled in valleys", and the production of "vast quantities of goods".[3]

Carl Troll has argued that the development of the Inca state in the central Andes was aided by conditions that allow for the elaboration of the staple food chuño. Chuño, which can be stored for long periods, is made of potato dried at the freezing temperatures that are common at nighttime in the southern Peruvian highlands. Such a link between the Inca state and chuño has been questioned, as other crops such as maize can also be dried with only sunlight.[4]

Troll also argued that llamas, the Incas' pack animal, can be found in their largest numbers in this very same region.[4] The maximum extent of the Inca Empire roughly coincided with the distribution of llamas and alpacas, the only large domesticated animals in Pre-Hispanic America.[5]

As a third point Troll pointed out irrigation technology as advantageous to Inca state-building.[6] While Troll theorized concerning environmental influences on the Inca Empire, he opposed environmental determinism, arguing that culture lay at the core of the Inca civilization.[6]

Origin Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, children of the Inti, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, circa 1615

Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, children of the Inti, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, circa 1615The Inca people were a pastoral tribe in the Cusco area around the 12th century. Indigenous Peruvian oral history tells an origin story of three caves. The center cave at Tampu T'uqu (Tambo Tocco) was named Qhapaq T'uqu ("principal niche", also spelled Capac Tocco). The other caves were Maras T'uqu (Maras Tocco) and Sutiq T'uqu (Sutic Tocco).[7] Four brothers and four sisters stepped out of the middle cave. They were: Ayar Manco, Ayar Cachi, Ayar Awqa (Ayar Auca) and Ayar Uchu; and Mama Ocllo, Mama Raua, Mama Huaco and Mama Qura (Mama Cora). Out of the side caves came the people who were to be the ancestors of all the Inca clans.

Manco Cápac, First Inca, 1 of 14 Portraits of Inca Kings, Probably mid-18th century. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum

Manco Cápac, First Inca, 1 of 14 Portraits of Inca Kings, Probably mid-18th century. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn MuseumAyar Manco carried a magic staff made of the finest gold. Where this staff landed, the people would live. They traveled for a long time. On the way, Ayar Cachi boasted about his strength and power. His siblings tricked him into returning to the cave to get a sacred llama. When he went into the cave, they trapped him inside to get rid of him.

Ayar Uchu decided to stay on the top of the cave to look over the Inca people. The minute he proclaimed that, he turned to stone. They built a shrine around the stone and it became a sacred object. Ayar Auca grew tired of all this and decided to travel alone. Only Ayar Manco and his four sisters remained.

Finally, they reached Cusco. The staff sank into the ground. Before they arrived, Mama Ocllo had already borne Ayar Manco a child, Sinchi Roca. The people who were already living in Cusco fought hard to keep their land, but Mama Huaca was a good fighter. When the enemy attacked, she threw her bolas (several stones tied together that spun through the air when thrown) at a soldier (gualla) and killed him instantly. The other people became afraid and ran away.

After that, Ayar Manco became known as Manco Cápac, the founder of the Inca. It is said that he and his sisters built the first Inca homes in the valley with their own hands. When the time came, Manco Cápac turned to stone like his brothers before him. His son, Sinchi Roca, became the second emperor of the Inca.[8]

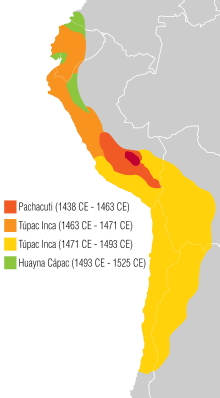

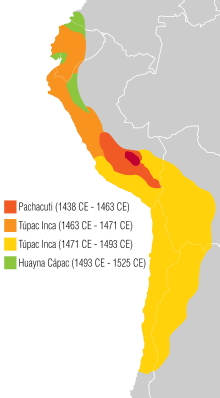

Kingdom of Cusco Inca expansion (1438–1533)

Inca expansion (1438–1533)Under the leadership of Manco Cápac, the Inca formed the small city-state Kingdom of Cusco (Quechua Qusqu', Qosqo). In 1438, they began a far-reaching expansion under the command of Sapa Inca (paramount leader) Pachacuti-Cusi Yupanqui, whose name meant "earth-shaker". The name of Pachacuti was given to him after he conquered the Tribe of Chancas (modern Apurímac). During his reign, he and his son Tupac Yupanqui brought much of the modern-day territory of Peru under Inca control.[9]

Reorganization and formationPachacuti reorganized the kingdom of Cusco into the Tahuantinsuyu, which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provincial governments with strong leaders: Chinchasuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Kuntisuyu (SW) and Qullasuyu (SE).[10] Pachacuti is thought to have built Machu Picchu, either as a family home or summer retreat, although it may have been an agricultural station.[11]

Pachacuti sent spies to regions he wanted in his empire and they brought to him reports on political organization, military strength and wealth. He then sent messages to their leaders extolling the benefits of joining his empire, offering them presents of luxury goods such as high quality textiles and promising that they would be materially richer as his subjects.

Most accepted the rule of the Inca as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully. Refusal to accept Inca rule resulted in military conquest. Following conquest the local rulers were executed. The ruler's children were brought to Cusco to learn about Inca administration systems, then return to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate them into the Inca nobility and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

Expansion and consolidationTraditionally the son of the Inca ruler led the army. Pachacuti's son Túpac Inca Yupanqui began conquests to the north in 1463 and continued them as Inca ruler after Pachacuti's death in 1471. Túpac Inca's most important conquest was the Kingdom of Chimor, the Inca's only serious rival for the Peruvian coast. Túpac Inca's empire then stretched north into what are today Ecuador and Colombia.

Túpac Inca's son Huayna Cápac added a small portion of land to the north in what is today Ecuador. At its height, the Inca Empire included modern-day Peru, what are today western and south central Bolivia, southwest Ecuador and Colombia and a large portion of modern-day Chile, at the north of the Maule River. Traditional historiography claims the advance south halted after the Battle of the Maule where they met determined resistance from the Mapuche.[12]

This view is challenged by historian Osvaldo Silva who argues instead that it was the social and political framework of the Mapuche that posed the main difficulty in imposing imperial rule.[12] Silva does accept that the battle of the Maule was a stalemate, but argues the Incas lacked incentives for conquest they had had when fighting more complex societies such as the Chimú Empire.[12]

Silva also disputes the date given by traditional historiography for the battle: the late 15th century during the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui (1471–93).[12] Instead, he places it in 1532 during the Inca Civil War.[12] Nevertheless, Silva agrees on the claim that the bulk of the Incan conquests were made during the late 15th century.[12] At the time of the Incan Civil War an Inca army was, according to Diego de Rosales, subduing a revolt among the Diaguitas of Copiapó and Coquimbo.[12]

The empire's push into the Amazon Basin near the Chinchipe River was stopped by the Shuar in 1527.[13] The empire extended into corners of what are today the north of Argentina and part of the southern Colombia. However, most of the southern portion of the Inca empire, the portion denominated as Qullasuyu, was located in the Altiplano.

The Inca Empire was an amalgamation of languages, cultures and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. The Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labour. The following quote describes a method of taxation:

For as is well known to all, not a single village of the highlands or the plains failed to pay the tribute levied on it by those who were in charge of these matters. There were even provinces where, when the natives alleged that they were unable to pay their tribute, the Inca ordered that each inhabitant should be obliged to turn in every four months a large quill full of live lice, which was the Inca's way of teaching and accustoming them to pay tribute.[14]

Inca Civil War and Spanish conquest The first image of the Inca in Europe, Pedro Cieza de León, Crónica del Perú, 1553

The first image of the Inca in Europe, Pedro Cieza de León, Crónica del Perú, 1553Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro and his brothers explored south from what is today Panama, reaching Inca territory by 1526.[15] It was clear that they had reached a wealthy land with prospects of great treasure, and after another expedition in 1529 Pizarro traveled to Spain and received royal approval to conquer the region and be its viceroy. This approval was received as detailed in the following quote: "In July 1529 the Queen of Spain signed a charter allowing Pizarro to conquer the Incas. Pizarro was named governor and captain of all conquests in Peru, or New Castile, as the Spanish now called the land".[16]

When the conquistadors returned to Peru in 1532, a war of succession between the sons of Sapa Inca Huayna Capac, Huáscar and Atahualpa, and unrest among newly conquered territories weakened the empire. Perhaps more importantly, smallpox, influenza, typhus and measles had spread from Central America. The first epidemic of European disease in the Inca Empire was probably in the 1520s, killing Huayna Capac, his designated heir, and an unknown, probably large, number of other Incan subjects.[17]

The forces led by Pizarro consisted of 168 men, along with one cannon and 27 horses. The conquistadors were armed with lances, arquebuses, steel armor and long swords. In contrast, the Inca used weapons made out of wood, stone, copper and bronze, while using an Alpaca fiber based armor, putting them at significant technological disadvantage—none of their weapons could pierce the Spanish steel armor. In addition, due to the absence of horses in Peru, the Inca did not develop tactics to fight cavalry. However, the Inca were still effective warriors, being able to successfully fight the Mapuche, who later would strategically defeat the Spanish as they expanded further south.

The first engagement between the Inca and the Spanish was the Battle of Puná, near present-day Guayaquil, Ecuador, on the Pacific Coast; Pizarro then founded the city of Piura in July 1532. Hernando de Soto was sent inland to explore the interior and returned with an invitation to meet the Inca, Atahualpa, who had defeated his brother in the civil war and was resting at Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops, that were at the moment armed only with hunting tools (knives and lassos for hunting llamas).

Pizarro and some of his men, most notably a friar named Vincente de Valverde, met with the Inca, who had brought only a small retinue. The Inca offered them ceremonial chicha in a golden cup, which the Spanish rejected. The Spanish interpreter, Friar Vincente, read the "Requerimiento" that demanded that he and his empire accept the rule of King Charles I of Spain and convert to Christianity. Atahualpa dismissed the message and asked them to leave. After this, the Spanish began their attack against the mostly unarmed Inca, captured Atahualpa as hostage, and forced the Inca to collaborate.

Atahualpa offered the Spaniards enough gold to fill the room he was imprisoned in and twice that amount of silver. The Inca fulfilled this ransom, but Pizarro deceived them, refusing to release the Inca afterwards. During Atahualpa's imprisonment, Huáscar was assassinated elsewhere. The Spaniards maintained that this was at Atahualpa's orders; this was used as one of the charges against Atahualpa when the Spaniards finally executed him, in August 1533.[18]

Although "defeat" often implies an unwanted loss in battle, many of the diverse ethnic groups ruled by the Inca "welcomed the Spanish invaders as liberators and willingly settled down with them to share rule of Andean farmers and miners".[19] Many regional leaders, called Kurakas, continued to serve the Spanish overlords, called encomenderos, as they had served the Inca overlords. Other than efforts to spread the religion of Christianity, the Spanish benefited from and made little effort to change the society and culture of the former Inca Empire until the rule of Francisco de Toledo as viceroy from 1569 to 1581.[20]

End of the Inca Empire Atahualpa, the last Sapa Inca of the empire, was executed by the Spanish on 29 August 1533.

Atahualpa, the last Sapa Inca of the empire, was executed by the Spanish on 29 August 1533. Facade of the Convent of Santo Domingo in Cusco, built on the base of the Coricancha

Facade of the Convent of Santo Domingo in Cusco, built on the base of the CoricanchaThe Spanish installed Atahualpa's brother Manco Inca Yupanqui in power; for some time Manco cooperated with the Spanish while they fought to put down resistance in the north. Meanwhile, an associate of Pizarro, Diego de Almagro, attempted to claim Cusco. Manco tried to use this intra-Spanish feud to his advantage, recapturing Cusco in 1536, but the Spanish retook the city afterwards. Manco Inca then retreated to the mountains of Vilcabamba and established the small Neo-Inca State, where he and his successors ruled for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or inciting revolts against them. In 1572 the last Inca stronghold was conquered and the last ruler, Túpac Amaru, Manco's son, was captured and executed.[21] This ended resistance to the Spanish conquest under the political authority of the Inca state.

After the fall of the Inca Empire many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed, including their sophisticated farming system, known as the vertical archipelago model of agriculture.[22] Spanish colonial officials used the Inca mita corvée labor system for colonial aims, sometimes brutally. One member of each family was forced to work in the gold and silver mines, the foremost of which was the titanic silver mine at Potosí. When a family member died, which would usually happen within a year or two, the family was required to send a replacement.[23]

Although smallpox is usually presumed to have spread through the Empire before the arrival of the Spaniards, the devastation is also consistent with other theories.[24] Beginning in Colombia, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived in the empire. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Smallpox was only the first epidemic.[25] Other diseases, including a probable typhus outbreak in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618, all ravaged the Inca people.

There would be periodic attempts by indigenous leaders to expel the Spanish colonists and re-create the Inca Empire until the late 18th century. See Juan Santos Atahualpa and Túpac Amaru II.

^ Upton, Gary and von Hagen, Adriana (2015), Encyclopedia of the Incas, New York: Rowand & Littlefield, p. 2. Some scholars cite 6 or 7 pristine civilizations. ISBN 0804715165. ^ McEwan, Gordon F. (2006), The Incas: New Perspectives Archived 11 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 65 ^ Spalding, Karen (1984), Huarocochí Stanford University Press: Stanford, page 77 ^ a b Gade, Daniel (2016). "Urubamba Verticality: Reflections on Crops and Diseases". Spell of the Urubamba: Anthropogeographical Essays on an Andean Valley in Space and Time. p. 86. ISBN 978-3-319-20849-7. ^ Hardoy, Jorge Henríque (1973). Pre-Columbian Cities. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8027-0380-4. ^ a b Gade, Daniel W. (1996). "Carl Troll on Nature and Culture in the Andes (Carl Troll über die Natur und Kultur in den Anden)". Erdkunde. 50 (4): 301–16. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.1996.04.02. ^ McEwan 2008, p. 57. ^ McEwan 2008, p. 69. ^ Demarest, Arthur Andrew; Conrad, Geoffrey W. (1984). Religion and Empire: The Dynamics of Aztec and Inca Expansionism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-521-31896-3. ^ The three laws of Tawantinsuyu are still referred to in Bolivia these days as the three laws of the Qullasuyu. ^ Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World. New York: Fawcett Columbine. pp. 60–62. ISBN 0-449-90496-2. ^ a b c d e f g Silva Galdames, Osvaldo (1983). "¿Detuvo la batalla del Maule la expansión inca hacia el sur de Chile?". Cuadernos de Historia (in Spanish). 3: 7–25. Retrieved 10 January 2019. ^ Ernesto Salazar (1977). An Indian federation in lowland Ecuador (PDF). International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 13. Retrieved 16 February 2013. ^ Starn, Orin; Kirk, Carlos Iván; Degregori, Carlos Iván (2009). The Peru Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-8750-3. ^ *Juan de Samano (9 October 2009). "Relacion de los primeros descubrimientos de Francisco Pizarro y Diego de Almagro, 1526". bloknot.info (A. Skromnitsky). Retrieved 10 October 2009. ^ Somervill, Barbara (2005). Francisco Pizarro: Conqueror of the Incas. Compass Point Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7565-1061-9. ^ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 9780631176770. ^ McEwan 2008, p. 79. ^ Raudzens, George, ed. (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial Conquest. Boston: Brill Academic. p. xiv. ^ Mumford, Jeremy Ravi (2012), Vertical Empire, Duke University Press: Durham, pages 19-30, 56-57. ISBN 9780822353102. ^ McEwan 2008, p. 31. ^ Sanderson 1992, p. 76. ^ Wiedner, Donald L. (April 1960). "Forced Labor in Colonial Peru". The Americas. 16 (4): 357–383. doi:10.2307/978993. ISSN 0003-1615. ^ "El Niño, Catastrophism, and Culture Change in Ancient America — Daniel H. Sandweiss, Jeffrey Quilter". www.hup.harvard.edu. Retrieved 7 August 2022. ^ Millersville University Silent Killers of the New World Archived 3 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine