قبة الصخرة

( Dome of the Rock )

The Dome of the Rock (Arabic: قبة الصخرة, romanized: Qubbat aṣ-Ṣakhra) is an Islamic shrine at the center of the Al-Aqsa mosque compound on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is the world's oldest surviving work of Islamic architecture, the earliest archaeologically attested religious structure to be built by a Muslim ruler and its inscriptions contain the earliest epigraphic proclamations of Islam and of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Its initial construction was undertaken by the Umayyad Caliphate on the orders of Abd al-Malik during the Second Fitna in 691–692 CE, and it has since been situated on top of the site of the Second Jewish Temple (built in c. 516 BCE to replace the destroyed Solomon's Temple and rebuilt by Herod the Great), which was destroyed by the Roma...Read more

The Dome of the Rock (Arabic: قبة الصخرة, romanized: Qubbat aṣ-Ṣakhra) is an Islamic shrine at the center of the Al-Aqsa mosque compound on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is the world's oldest surviving work of Islamic architecture, the earliest archaeologically attested religious structure to be built by a Muslim ruler and its inscriptions contain the earliest epigraphic proclamations of Islam and of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Its initial construction was undertaken by the Umayyad Caliphate on the orders of Abd al-Malik during the Second Fitna in 691–692 CE, and it has since been situated on top of the site of the Second Jewish Temple (built in c. 516 BCE to replace the destroyed Solomon's Temple and rebuilt by Herod the Great), which was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. The original dome collapsed in 1015 and was rebuilt in 1022–23.

Its architecture and mosaics were patterned after nearby Byzantine churches and palaces, although its outside appearance was significantly changed during the Ottoman period and again in the modern period, notably with the addition of the gold-plated roof, in 1959–61 and again in 1993. The octagonal plan of the structure may have been influenced by the Byzantine-era Church of the Seat of Mary (also known as Kathisma in Greek and al-Qadismu in Arabic), which was built between 451 and 458 on the road between Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

The Foundation Stone (or Noble Rock) that the temple was built over bears great significance in the Abrahamic religions as the place where God created the world as well as the first human, Adam. It is also believed to be the site where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son, and as the place where God's divine presence is manifested more than in any other place, towards which Jews turn during prayer. The site's great significance for Muslims derives from traditions connecting it to the creation of the world and the belief that the Night Journey of Muhammad began from the rock at the centre of the structure.

Designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, it has been called "Jerusalem's most recognizable landmark" along with two nearby Old City structures: the Western Wall and the "Resurrection Rotunda" in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Its Islamic inscriptions proved to be a milestone, as afterward they became a common feature in Islamic structures and almost always mention Muhammad. The Dome of the Rock remains a "unique monument of Islamic culture in almost all respects", including as a "work of art and as a cultural and pious document", according to art historian Oleg Grabar.

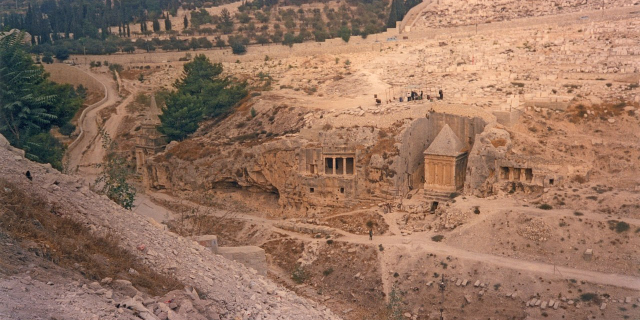

Reconstruction of Herod's Temple as seen from the east (Holyland Model of Jerusalem, 1966)

Reconstruction of Herod's Temple as seen from the east (Holyland Model of Jerusalem, 1966)The Dome of the Rock is situated in the center of the Temple Mount, the site of Solomon's Temple and the Second Jewish Temple, which had been greatly expanded under Herod the Great in the 1st century BCE. Herod's Temple was destroyed in 70 CE by the Romans, and after the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, a Roman temple to Jupiter Capitolinus was built at the site by Emperor Hadrian.[1]

Jerusalem was ruled by the Byzantine Empire throughout the 4th to 6th centuries. During this time, Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem began to develop.[2] The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built under Constantine in the 320s, but the Temple Mount was left undeveloped after a failed project of restoration of the Jewish Temple under Emperor Julian.[3]

In 638 CE, Byzantine Jerusalem was conquered by the Arab armies of Umar ibn al-Khattab,[4] second Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate. Umar was advised by Ka'b al-Ahbar, a Jewish rabbi who converted to Islam,[5] that the site is identical with the site of the former Jewish Temples in Jerusalem.[6] Among the first Muslims, Jerusalem was referred to as Madinat bayt al-Maqdis ("City of the Temple").[7]

Umayyads Original constructionThe initial octagonal structure of the Dome of the Rock and its round wooden dome had basically the same shape as it does today.[8] It was built by the order of the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705).[9] According to Sibt ibn al-Jawzi (1185–1256), construction started in 685/86, while al-Suyuti (1445–1505) holds that its commencement year was 688.[10] A dedicatory inscription in Kufic script is preserved inside the dome. The date is recorded as AH 72 (691/2 CE), the year most historians believe the construction of the original Dome was completed.[11] An alternative interpretation of the inscription claims that it indicates the year when construction started.[12] In this inscription, the name of "al-Malik" was deleted and replaced by the name of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833). This alteration of the original inscription was first noted by Melchior de Vogüé in 1864.[13] Some scholars have suggested that the dome was added to an existing building, built either by Muawiyah I (r. 661–680),[14] or indeed a Byzantine building dating to before the Muslim conquest, built under Heraclius (r. 610–641).[15]

The Dome of the Rock's architecture and mosaics were patterned after nearby Byzantine churches and palaces.[16] The supervisor and engineer in charge of the project were Raja ibn Haywa, Yazid ibn Salam, and the latter's son Baha.[17][16][18] Raja was a Muslim theologian and native of Beisan, and Yazid and Baha were mawali (non-Arab, Muslim converts; clients) of Abd al-Malik from Jerusalem. Abd al-Malik was represented in the supervision of the construction by his son Sa'id al-Khayr.[17] The Caliph employed expert works from across his domain, at the time restricted to Syria and Egypt,[17] who were presumably Christians.[18] Construction cost was reportedly seven times the yearly tax income of Egypt.[19] The historian K. A. C. Creswell noted that those who built the shrine used the measurements of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The diameter of the dome of the shrine is 20.20 m (66.3 ft) and its height 20.48 m (67.2 ft), while the diameter of the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is 20.90 m (68.6 ft) and its height 21.05 m (69.1 ft).

Motivations for constructionNarratives by the medieval sources about Abd al-Malik's motivations in building the Dome of the Rock vary.[20] At the time of its construction, the Caliph was engaged in war with Christian Byzantium and its Syrian Christian allies on the one hand and with the rival caliph Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, who controlled Mecca, the annual destination of Muslim pilgrimage, on the other hand.[20][21] Thus, one series of explanations was that Abd al-Malik intended for the Dome of the Rock to be a religious monument of victory over the Christians that would distinguish Islam's uniqueness within the common Abrahamic religious setting of Jerusalem, home of the two older Abrahamic faiths, Judaism and Christianity.[20][22] The historian Shelomo Dov Goitein has argued that the Dome of the Rock was intended to compete with the many fine buildings of worship of other religions: "The very form of a rotunda, given to the Qubbat as-Sakhra, although it was foreign to Islam, was destined to rival the many Christian domes."[23]

The other main explanation holds that Abd al-Malik, in the heat of the war with Ibn al-Zubayr, sought to build the structure to divert the focus of the Muslims in his realm from the Ka'aba in Mecca, where Ibn al-Zubayr would publicly condemn the Umayyads during the annual pilgrimage to the sanctuary.[20][21][22] Though most modern historians dismiss the latter account as a product of anti-Umayyad propaganda in the traditional Muslim sources and doubt that Abd al-Malik would attempt to alter the sacred Muslim requirement of fulfilling the pilgrimage to the Ka'aba, other historians concede that this cannot be conclusively dismissed.[20][21][22]

Abbasids and FatimidsThe building was severely damaged by earthquakes in 808 and again in 846.[24] The dome collapsed in an earthquake in 1015 and was rebuilt in 1022–23. The mosaics on the drum were repaired in 1027–28.[25] The earthquake of 1033 resulted in the introduction of wooden beams to enforce the dome.[26]

Crusaders Depiction of the Templum Domini on the reverse side of the seal of the Knights Templar

Depiction of the Templum Domini on the reverse side of the seal of the Knights TemplarFor centuries Christian pilgrims were able to come and experience the Temple Mount, but escalating violence against pilgrims to Jerusalem (Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, who ordered the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre, was an example) resulted in the Crusades.[27] The Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099 and the Dome of the Rock was given to the Augustinians, who turned it into a church, while the nearby Al-Aqsa main prayer hall or Qibli Mosque first became a royal palace for a while, and then for much of the 12th century the headquarters of the Knights Templar. The Templars, active from c. 1119, identified the Dome of the Rock as the site of the Temple of Solomon.[clarification needed] The Templum Domini, as they called the Dome of the Rock, featured on the official seals of the Order's Grand Masters (such as Everard des Barres and Renaud de Vichiers), and soon became the architectural model for round Templar churches across Europe.[28]

Ayyubids and MamluksJerusalem was recaptured by Saladin on 2 October 1187, and the Dome of the Rock was reconsecrated as a Muslim shrine. The cross on top of the dome was replaced by a crescent, and a wooden screen was placed around the rock below. Saladin's nephew al-Malik al-Mu'azzam Isa carried out other restorations within the building, and added the porch to the Jami'a Al-Aqsa.

The Dome of the Rock was the focus of extensive royal patronage by the sultans during the Mamluk period, which lasted from 1260 until 1516.

Ottoman period (1517–1917)During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), the exterior of the Dome of the Rock was covered with tiles. This work took seven years.[citation needed] Some of the interior decoration was added in the Ottoman period.[citation needed]

Adjacent to the Dome of the Rock, the Ottomans built the free-standing Dome of the Prophet in 1620.[citation needed]

Large-scale renovation was undertaken during the reign of Mahmud II in 1817.[citation needed] In a major restoration project undertaken in 1874–75 during the reign of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülaziz, all the tiles on the west and southwest walls of the octagonal part of the building were removed and replaced by copies that had been made in Turkey.[29][30]

1920s photograph

1920s photographHaj Amin al-Husseini, appointed Grand Mufti by the British in 1917, along with Yaqub al-Ghusayn, implemented the restoration of the Dome of the Rock and the Jami Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem.

Parts of the Dome of the Rock collapsed during the 11 July 1927 earthquake, and the walls were left badly cracked,[31] damaging many of the repairs that had taken place over previous years.[citation needed]

Jordanian ruleIn 1955, an extensive program of renovation was begun by the government of Jordan, with funds supplied by Arab governments and Turkey. The work included replacement of large numbers of tiles dating back to the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, which had become dislodged by heavy rain. In 1965, as part of this restoration, the dome was covered with a durable aluminium bronze alloy made in Italy that replaced the lead exterior. Before 1959, the dome was covered in blackened lead. In the course of substantial restoration carried out from 1959 to 1962, the lead was replaced by aluminum-bronze plates covered with gold leaf.

Israeli rule The Dome of the Rock in 2018

The Dome of the Rock in 2018A few hours after the Israeli flag was hoisted over the Dome of the Rock in 1967 during the Six-Day War, Israelis lowered it on the orders of Moshe Dayan and invested the Muslim waqf (religious trust) with the authority to manage the Temple Mount in order to "keep the peace".[32]

In 1993, the golden dome covering was refurbished following a donation of US$8.25 million by King Hussein of Jordan, who sold one of his houses in London to fund the 80 kilograms of gold required.[33]

Add new comment