فاس البالي

( Fes el Bali )Fes el Bali (Arabic: فاس البالي, romanized: Fās al-Bālī, lit. 'Old Fes', Berber languages: ⴼⴰⵙ ⴰⵇⴷⵉⵎ) is the oldest walled part of Fez, the second largest city of Morocco. Fes el Bali was founded as the capital of the Idrisid dynasty between 789 and 808 AD. UNESCO listed Fes el Bali, along with Fes Jdid, as a World Heritage Site in 1981 under the name Medina of Fez. The World Heritage Site includes Fes el Bali's urban fabric and walls as well as a buffer zone outside of the walls that is intended to preserve the visual integrity of the location. Fes el Bali is, along with Fes Jdid and the French-created Ville Nouvelle or “New Town”, one of the three main districts in Fez.

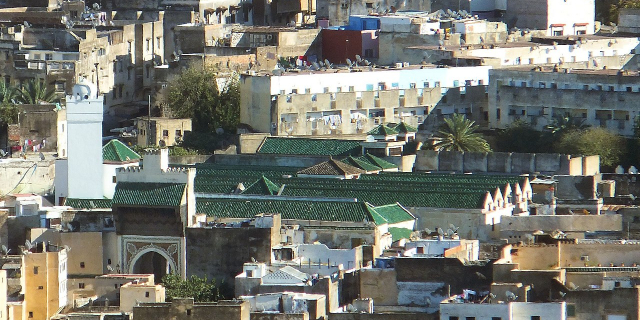

The old medina of Fez. View over Tala'a Kebira street and the minaret of the Bou Inania Madrasa (left) and another mosque (right).

The old medina of Fez. View over Tala'a Kebira street and the minaret of the Bou Inania Madrasa (left) and another mosque (right). View of Bab Ftouh, the southern gate of the city, in the early 20th century.

View of Bab Ftouh, the southern gate of the city, in the early 20th century.

As the capital for his newly acquired empire, Idris ibn Abdallah chose to build a new town on the right bank of the Fez River in AD 789. Many of the first inhabitants were refugees fleeing from an uprising in Cordoba (modern-day Spain).[1] However, in 809 his son, Idris II, decided to found a capital of his own on the opposite bank of the Fez River. Even though they were only separated by a relatively small river the cities developed separately and became two individual cities until they were unified in the 11th century by the Almoravids. There were many refugees who decided to settle in the new city this time too, however this time they fled from an uprising in Kairouan (in modern Tunisia).[1] The University of Al-Karaouine (or al-Qarawiyyin) is recorded by traditional sources as having been founded by one of these refugees, Fatima al-Fihri, in 859. UNESCO and Guinness World Records consider it the oldest continuously operating university in the world.[2][3] The Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque (or Mosque of the Andalusians), on the opposite shore of the river, is likewise traditionally believed to have been founded by her sister in the same year.[4][5]

Under the Almoravids, Fez lost its status as a capital, which was moved to the newly created Marrakesh. During Almohad rule (12th-13th centuries), Fez was a thriving merchant city, even though it was not a capital.[4][6] It even became the largest city in the world during that time, with approximately 200,000 people living there.[7]

After defeating the Almohads in Morocco, the Marinids moved the capital from Marrakesh back to Fez.[8] This marked the beginning of the greatest period of the history for Fes.[8] When the Marinids moved the capital to Fez in 1276 they started building a new town outside the old city walls. At first it was called Madinat al-Bayda ("the White City"), but it quickly became known as Fes el-Jdid ("New Fez"), while the old city became known as Fes el-Bali ("Old Fez").[4]: 62 The Marinids built the first true madrasas in Morocco, which include many of the city's most notable architectural monuments such as the Bou Inania Madrasa, the Al-Attarin Madrasa, and the Sahrij Madrasa.[9][10][11]

The Saadian dynasty (16th and early 17th centuries), who used Marrakesh again as their capital, did not lavish much attention on Fez, with the exception of the ornate ablutions pavilions added to the Qarawiyyin Mosque's courtyard during their time.[12] They built a number of new forts and bastions around the city which appear to have been aimed at keeping control over the local population. They were mostly located on higher ground overlooking Fes el-Bali, from which they would have been easily able to bombard the city with canons.[4][6] These include the Kasbah Tamdert, just inside the city walls near Bab Ftouh, and the forts of Borj Nord (Borj al-Shamali) on the hills to the north, Borj Sud (Borj al-Janoub) on the hills to the south, and the Borj Sheikh Ahmed to the west, at a point in Fes el-Jdid's walls that was closest to Fes el-Bali. These were built in the late 16th century, mostly by Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur.[6][4]

It was only when the founder of the Alaouite dynasty, Moulay Rashid, took Fez in 1666 that the city saw a revival again, albeit briefly.[6] He built the Kasbah Cherarda (also known as the Kasbah al-Khemis) to the northwest of Fes el-Jdid to house a large part of his tribal troops.[4][6] He also restored or rebuilt what became known as the Kasbah an-Nouar, which became the living quarters of his followers from the Tafilalt region (the Alaouite dynasty's ancestral home). For this reason, the kasbah was also known as the Kasbah Filala ("Kasbah of the people from Tafilalt").[4] Moulay Isma'il, his successor, chose nearby Meknès as his capital instead, but he did restore or rebuild some major monuments in Fes el-Bali, such as the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II. While the succession conflicts between Moulay Isma'il's sons were another low point in the city's history, the city's fortunes rose more definitively after 1757 with the reign of Moulay Muhammad Ibn Abdallah and under his successors.[4]

The last major change to Fez's topography before the 20th century was made during the reign of Moulay Hasan I (1873-1894), who finally connected Fes el-Jdid and Fes el-Bali by building a walled corridor between them.[4][6] Within this new corridor, between the two cities, were built new gardens and summer palaces used by the royals and the capital's high society, such as the Jnan Sbil Gardens and the Dar Batha palace.[4][13]

In 1912 French colonial rule was instituted over Morocco following the Treaty of Fes. Fez ceased to be the center of power in Morocco as the capital was moved to Rabat, which remained the capital even after independence in 1956.[6] Starting under French resident general Hubert Lyautey, one important policy with long-term consequences was the decision to largely forego redevelopment of existing historic walled cities in Morocco and to intentionally preserve them as sites of historic heritage, still known today as "medinas". Instead, the French administration built new modern cities (the Villes Nouvelles) just outside the old cities, where European settlers largely resided with modern Western-style amenities.[14][15][16] The existence today of a Ville Nouvelle ("New City") alongside a historic medina of Fez was thus a consequence of this early colonial decision-making and had a wider impact on the entire city's development.[16] While new colonial policies preserved historic monuments, it also had other consequences in the long-term by stalling urban development in these heritage areas.[14] Wealthy and bourgeois Moroccans started moving into the more modern Ville Nouvelles during the interwar period.[17][6] By contrast, the old city (medina) of Fez was increasingly settled by poorer rural migrants from the countryside.[6]: 26

Today Fes el-Bali and the larger historic medina is a major tourism destination due to its historical heritage. In recent years efforts have been underway to restore and rehabilitate its historic fabric, ranging from restorations of individual monuments to attempts to rehabilitate the Fez River.[18][19][20][21]

Add new comment