长城

( Great Wall of China )

The Great Wall of China (traditional Chinese: 萬里長城; simplified Chinese: 万里长城; pinyin: Wànlǐ Chángchéng, literally "ten thousand li long wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic groups from the Eurasian Steppe. Several walls were built from as early as the 7th century BC, with selective stretches later joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China. Little of the Qin wall remains. Later on, many successive dynasties built and maintained multiple stretches of border walls. The best-known sections of the wall were built by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Apart from defense, other purposes of the Great Wall have inclu...Read more

The Great Wall of China (traditional Chinese: 萬里長城; simplified Chinese: 万里长城; pinyin: Wànlǐ Chángchéng, literally "ten thousand li long wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic groups from the Eurasian Steppe. Several walls were built from as early as the 7th century BC, with selective stretches later joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China. Little of the Qin wall remains. Later on, many successive dynasties built and maintained multiple stretches of border walls. The best-known sections of the wall were built by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Apart from defense, other purposes of the Great Wall have included border controls, allowing the imposition of duties on goods transported along the Silk Road, regulation or encouragement of trade and the control of immigration and emigration. Furthermore, the defensive characteristics of the Great Wall were enhanced by the construction of watchtowers, troop barracks, garrison stations, signaling capabilities through the means of smoke or fire, and the fact that the path of the Great Wall also served as a transportation corridor.

The frontier walls built by different dynasties have multiple courses. Collectively, they stretch from Liaodong in the east to Lop Lake in the west, from the present-day Sino–Russian border in the north to Tao River (Taohe) in the south; along an arc that roughly delineates the edge of the Mongolian steppe; spanning 21,196.18 km (13,170.70 mi) in total. Today, the defensive system of the Great Wall is generally recognized as one of the most impressive architectural feats in history.

The Great Wall of the Qin stretches from Lintao to Liaodong.

The Great Wall of the Qin stretches from Lintao to Liaodong.The Chinese were already familiar with the techniques of wall-building by the time of the Spring and Autumn period between the 8th and 5th centuries BC.[1] During this time and the subsequent Warring States period, the states of Qin, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Han, Yan, and Zhongshan[2][3] all constructed extensive fortifications to defend their own borders. Built to withstand the attack of small arms such as swords and spears, these walls were made mostly of stone or by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

The Great Wall of the Han is the longest of all walls, from Mamitu, near Yumenguan, to Liaodong.

The Great Wall of the Han is the longest of all walls, from Mamitu, near Yumenguan, to Liaodong.King Zheng of Qin conquered the last of his opponents and unified China as the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty ("Qin Shi Huang") in 221 BC. Intending to impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, he ordered the destruction of the sections of the walls that divided his empire among the former states. To position the empire against the Xiongnu people from the north, however, he ordered the building of new walls to connect the remaining fortifications along the empire's northern frontier. "Build and move on" was a central guiding principle in constructing the wall, implying that the Chinese were not erecting a permanently fixed border.[4]

Transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders always tried to use local resources. Stones from the mountains were used over mountain ranges, while rammed earth was used for construction in the plains. There are no surviving historical records indicating the exact length and course of the Qin walls. Most of the ancient walls have eroded away over the centuries, and very few sections remain today. The human cost of the construction is unknown, but it has been estimated by some authors that hundreds of thousands[5] of workers died building the Qin wall. Later, the Han,[6] the Northern dynasties and the Sui all repaired, rebuilt, or expanded sections of the Great Wall at great cost to defend themselves against northern invaders.[7] The Tang and Song dynasties did not undertake any significant effort in the region.[7] Dynasties founded by non-Han ethnic groups also built their border walls: the Xianbei-ruled Northern Wei, the Khitan-ruled Liao, Jurchen-led Jin and the Tangut-established Western Xia, who ruled vast territories over Northern China throughout centuries, all constructed defensive walls but those were located much to the north of the other Great Walls as we know it, within China's autonomous region of Inner Mongolia and in modern-day Mongolia itself.[8]

Ming era The extent of the Ming Empire and its walls

The extent of the Ming Empire and its wallsThe Great Wall concept was revived again under the Ming in the 14th century,[9] and following the Ming army's defeat by the Oirats in the Battle of Tumu. The Ming had failed to gain a clear upper hand over the Mongol tribes after successive battles, and the long-drawn conflict was taking a toll on the empire. The Ming adopted a new strategy to keep the nomadic tribes out by constructing walls along the northern border of China. Acknowledging the Mongol control established in the Ordos Desert, the wall followed the desert's southern edge instead of incorporating the bend of the Yellow River.

Unlike the earlier fortifications, the Ming construction was stronger and more elaborate due to the use of bricks and stone instead of rammed earth. Up to 25,000 watchtowers are estimated to have been constructed on the wall.[10] As Mongol raids continued periodically over the years, the Ming devoted considerable resources to repair and reinforce the walls. Sections near the Ming capital of Beijing were especially strong.[11] Qi Jiguang between 1567 and 1570 also repaired and reinforced the wall, faced sections of the ram-earth wall with bricks and constructed 1,200 watchtowers from Shanhaiguan Pass to Changping to warn of approaching Mongol raiders.[12] During the 1440s–1460s, the Ming also built a so-called "Liaodong Wall". Similar in function to the Great Wall (whose extension, in a sense, it was), but more basic in construction, the Liaodong Wall enclosed the agricultural heartland of the Liaodong province, protecting it against potential incursions by Jurchen-Mongol Oriyanghan from the northwest and the Jianzhou Jurchens from the north. While stones and tiles were used in some parts of the Liaodong Wall, most of it was in fact simply an earth dike with moats on both sides.[13]

Towards the end of the Ming, the Great Wall helped defend the empire against the Manchu invasions that began around 1600. Even after the loss of all of Liaodong, the Ming army held the heavily fortified Shanhai Pass, preventing the Manchus from conquering the Chinese heartland. The Manchus were finally able to cross the Great Wall in 1644, after Beijing had already fallen to Li Zicheng's short-lived Shun dynasty. Before this time, the Manchus had crossed the Great Wall multiple times to raid, but this time it was for conquest. The gates at Shanhai Pass were opened on May 25 by the commanding Ming general, Wu Sangui, who formed an alliance with the Manchus, hoping to use the Manchus to expel the rebels from Beijing.[14] The Manchus quickly seized Beijing, and eventually defeated both the Shun dynasty and the remaining Ming resistance, consolidating the rule of the Qing dynasty over all of China proper.[15]

Under Qing rule, China's borders extended beyond the walls and Mongolia was annexed into the empire, so constructions on the Great Wall were discontinued. On the other hand, the so-called Willow Palisade, following a line similar to that of the Ming Liaodong Wall, was constructed by the Qing rulers in Manchuria. Its purpose, however, was not defense but rather to prevent Han Chinese migration into Manchuria.[16]

Foreign accounts Part of the Great Wall of China (April 1853, X, p. 41)[17]

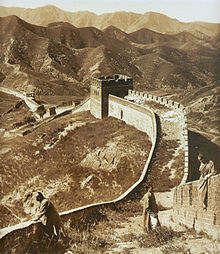

Part of the Great Wall of China (April 1853, X, p. 41)[17] The Great Wall in 1907

The Great Wall in 1907None of the Europeans who visited China or Mongolia in the 13th and 14th centuries, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, William of Rubruck, Marco Polo, Odoric of Pordenone and Giovanni de' Marignolli, mentioned the Great Wall.[18][19]

The North African traveler Ibn Battuta, who also visited China during the Yuan dynasty c. 1346, had heard about China's Great Wall, possibly before he had arrived in China.[20] He wrote that the wall is "sixty days' travel" from Zeitun (modern Quanzhou) in his travelogue Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling. He associated it with the legend of the wall mentioned in the Qur'an,[21] which Dhul-Qarnayn (commonly associated with Alexander the Great) was said to have erected to protect people near the land of the rising sun from the savages of Gog and Magog. However, Ibn Battuta could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it, suggesting that although there were remnants of the wall at that time, they were not significant.[22]

Soon after Europeans reached Ming China by ship in the early 16th century, accounts of the Great Wall started to circulate in Europe, even though no European was to see it for another century. Possibly one of the earliest European descriptions of the wall and of its significance for the defense of the country against the "Tartars" (i.e. Mongols) may be the one contained in João de Barros's 1563 Asia.[23] Other early accounts in Western sources include those of Gaspar da Cruz, Bento de Goes, Matteo Ricci, and Bishop Juan González de Mendoza,[24] the latter in 1585 describing it as a "superbious and mightie work" of architecture, though he had not seen it.[25] In 1559, in his work "A Treatise of China and the Adjoyning Regions", Gaspar da Cruz offers an early discussion of the Great Wall.[24] Perhaps the first recorded instance of a European actually entering China via the Great Wall came in 1605, when the Portuguese Jesuit brother Bento de Góis reached the northwestern Jiayu Pass from India.[26] Early European accounts were mostly modest and empirical, closely mirroring contemporary Chinese understanding of the Wall,[27] although later they slid into hyperbole,[28] including the erroneous but ubiquitous claim that the Ming walls were the same ones that were built by the first emperor in the 3rd century BC.[28]

When China opened its borders to foreign merchants and visitors after its defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars, the Great Wall became a main attraction for tourists. The travelogues of the later 19th century further enhanced the reputation and the mythology of the Great Wall.[29]

Add new comment