长江

( Yangtze )

The Yangtze, Yangzi or Changjiang (English: or ; simplified Chinese: 长江; traditional Chinese: 長江; pinyin: Cháng Jiāng; lit. 'long river') is the longest river in Eurasia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows 6,300 km (3,915 mi) in a generally easterly direction to the East China Sea. It is the fifth-largest primary river by discharge volume in the world. Its drainage basin comprises one-fifth of the land area of China, and is home to nearly one-third of the country's population.

The Yangtze has played a major role in t...Read more

The Yangtze, Yangzi or Changjiang (English: or ; simplified Chinese: 长江; traditional Chinese: 長江; pinyin: Cháng Jiāng; lit. 'long river') is the longest river in Eurasia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows 6,300 km (3,915 mi) in a generally easterly direction to the East China Sea. It is the fifth-largest primary river by discharge volume in the world. Its drainage basin comprises one-fifth of the land area of China, and is home to nearly one-third of the country's population.

The Yangtze has played a major role in the history, culture, and economy of China. For thousands of years, the river has been used for water, irrigation, sanitation, transportation, industry, boundary-marking, and war. The prosperous Yangtze Delta generates as much as 20% of China's GDP. The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze is the largest hydro-electric power station in the world that is in use. In mid-2014, the Chinese government announced it was building a multi-tier transport network, comprising railways, roads and airports, to create a new economic belt alongside the river.

The Yangtze flows through a wide array of ecosystems and is habitat to several endemic and threatened species including the Chinese alligator, the narrow-ridged finless porpoise, and also was the home of the now extinct Yangtze river dolphin (or baiji) and Chinese paddlefish, as well as the Yangtze sturgeon, which is extinct in the wild. In recent years, the river has suffered from industrial pollution, plastic pollution, agricultural runoff, siltation, and loss of wetland and lakes, which exacerbates seasonal flooding. Some sections of the river are now protected as nature reserves. A stretch of the upstream Yangtze flowing through deep gorges in western Yunnan is part of the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Although the mouth of the Yellow River has fluctuated widely north and south of the Shandong peninsula within the historical record, the Yangtze has remained largely static. Based on studies of sedimentation rates, however, it is unlikely that the present discharge site predates the late Miocene (c. 11 Ma).[1] Prior to this, its headwaters drained south into the Gulf of Tonkin along or near the course of the present Red River.[2]

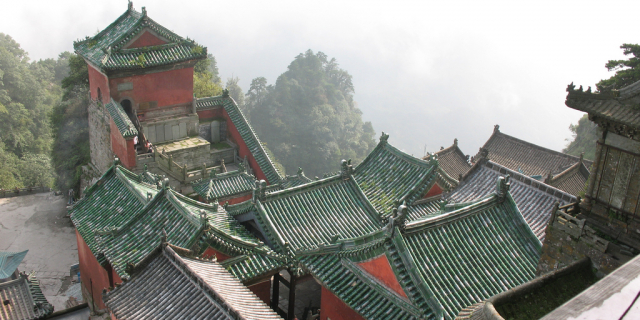

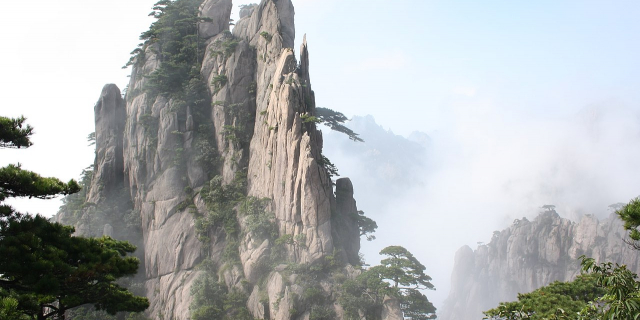

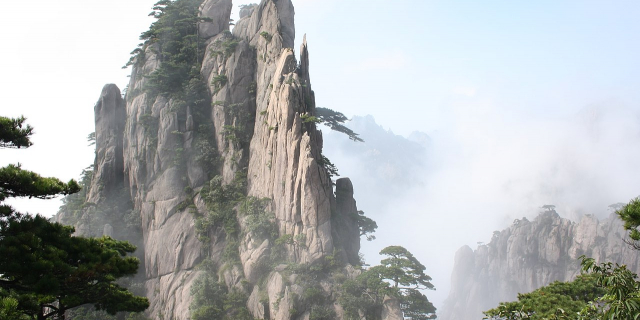

Afternoon in the jagged mountains rising from the Yangtze River gorgeEarly history

Afternoon in the jagged mountains rising from the Yangtze River gorgeEarly history

The Yangtze River is important to the cultural origins of southern China and Japan.[3] Human activity has been verified in the Three Gorges area as far back as 27,000 years ago,[4] and by the 5th millennium BC, the lower Yangtze was a major population center occupied by the Hemudu and Majiabang cultures, both among the earliest cultivators of rice. By the 3rd millennium BC, the successor Liangzhu culture showed evidence of influence from the Longshan peoples of the North China Plain.[5] What is now thought of as Chinese culture developed along the more fertile Yellow River basin; the "Yue" people of the lower Yangtze possessed very different traditions – blackening their teeth, cutting their hair short, tattooing their bodies, and living in small settlements among bamboo groves[6] – and were considered barbarous by the northerners.

The Central Yangtze valley was home to sophisticated Neolithic cultures.[7] Later it became the earliest part of the Yangtze valley to be integrated into the North Chinese cultural sphere. (Northern Chinese were active there since the Bronze Age).[8]

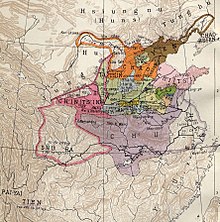

A map of the Warring States around 350 BC, showing the former coastline of the Yangtze delta

A map of the Warring States around 350 BC, showing the former coastline of the Yangtze deltaIn the lower Yangtze, two Yue tribes, the Gouwu in southern Jiangsu and the Yuyue in northern Zhejiang, display increasing Zhou (i.e., North Chinese) influence starting in the 9th century BC. Traditional accounts[9] credit these changes to northern refugees (Taibo and Zhongyong in Wu and Wuyi in Yue) who assumed power over the local tribes, though these are generally assumed to be myths invented to legitimate them to other Zhou rulers. As the kingdoms of Wu and Yue, they were famed as fishers, shipwrights, and sword-smiths. Adopting Chinese characters, political institutions, and military technology, they were among the most powerful states during the later Zhou. In the middle Yangtze, the state of Jing seems to have begun in the upper Han River valley a minor Zhou polity, but it adapted to native culture as it expanded south and east into the Yangtze valley. In the process, it changed its name to Chu.[10]

Whether native or nativizing, the Yangtze states held their own against the northern Chinese homeland: some lists credit them with three of the Spring and Autumn period's Five Hegemons and one of the Warring States' Four Lords. They fell in against themselves, however. Chu's growing power led its rival Jin to support Wu as a counter. Wu successfully sacked Chu's capital Ying in 506 BC, but Chu subsequently supported Yue in its attacks against Wu's southern flank. In 473 BC, King Goujian of Yue fully annexed Wu and moved his court to its eponymous capital at modern Suzhou. In 333 BC, Chu finally united the lower Yangtze by annexing Yue, whose royal family was said to have fled south and established the Minyue kingdom in Fujian. Qin was able to unite China by first subduing Ba and Shu on the upper Yangtze in modern Sichuan, giving them a strong base to attack Chu's settlements along the river.

The state of Qin conquered the central Yangtze region, previous heartland of Chu, in 278 BC, and incorporated the region into its expanding empire. Qin then used its connections along the Yangtze River the Xiang River to expand China into Hunan, Jiangxi and Guangdong, setting up military commanderies along the main lines of communication. At the collapse of the Qin Dynasty, these southern commanderies became the independent Nanyue Empire under Zhao Tuo while Chu and Han vied with each other for control of the north.

Since the Han dynasty, the region of the Yangtze River grew ever more important to China's economy. The establishment of irrigation systems (the most famous one is Dujiangyan, northwest of Chengdu, built during the Warring States period) made agriculture very stable and productive, eventually exceeding even the Yellow River region. The Qin and Han empires were actively engaged in the agricultural colonization of the Yangtze lowlands, maintaining a system of dikes to protect farmland from seasonal floods.[11] By the Song dynasty, the area along the Yangtze had become among the wealthiest and most developed parts of the country, especially in the lower reaches of the river. Early in the Qing dynasty, the region called Jiangnan (that includes the southern part of Jiangsu, the northern part of Zhejiang, and the southeastern part of Anhui) provided 1⁄3–1⁄2 of the nation's revenues.

The Yangtze has long been the backbone of China's inland water transportation system, which remained particularly important for almost two thousand years, until the construction of the national railway network during the 20th century. The Grand Canal connects the lower Yangtze with the major cities of the Jiangnan region south of the river (Wuxi, Suzhou, Hangzhou) and with northern China (all the way from Yangzhou to Beijing). The less well known ancient Lingqu Canal, connecting the upper Xiang River with the headwaters of the Guijiang, allowed a direct water connection from the Yangtze Basin to the Pearl River Delta.[12]

Historically, the Yangtze became the political boundary between north China and south China several times (see History of China) because of the difficulty of crossing the river. This occurred notably during the Southern and Northern Dynasties, and the Southern Song. Many battles took place along the river, the most famous being the Battle of Red Cliffs in 208 AD during the Three Kingdoms period.

The Yangtze was the site of naval battles between the Song dynasty and Jurchen Jin during the Jin–Song wars. In the Battle of Caishi of 1161, the ships of the Jin emperor Wanyan Liang clashed with the Song fleet on the Yangtze. Song soldiers fired bombs of lime and sulfur using trebuchets at the Jurchen warships. The battle was a Song victory that halted the invasion by the Jin.[13][14] The Battle of Tangdao was another Yangtze naval battle in the same year.

Politically, Nanjing was the capital of China several times, although most of the time its territory only covered the southeastern part of China, such as the Wu kingdom in the Three Kingdoms period, the Eastern Jin Dynasty, and during the Southern and Northern Dynasties and Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms periods. Only the Ming occupied most parts of China from their capital at Nanjing, though it later moved the capital to Beijing. The ROC capital was located in Nanjing in the periods 1911–12, 1927–37, and 1945–49.

Age of steamThe Jardine, the first steamship to sail the river, was built for Jardine, Matheson & Co. in 1835. This small vessel was to carry passengers and mail between Lintin Island, Macao, and Huangpu. However, the Chinese, draconian in their application of the rules relating to foreign vessels, were unhappy about a "fire-ship" steaming up the Canton River. The acting Viceroy of Liangguang issued an edict warning that she would be fired on if she attempted the trip.[15] On the Jardine's first trial run from Lintin Island the forts on both sides of the Bogue opened fire and she was forced to turn back. The Chinese authorities issued a further warning insisting that the ship leave Chinese waters. The Jardine in any case needed repairs and was sent to Singapore.[16]

Subsequently, Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary decided mainly on the "suggestions" of William Jardine to declare war on China. In mid-1840, a large fleet of warships appeared on the China coast, and with the first cannonball fired at a British ship, the Royal Saxon, the British started the first of the Opium Wars. Royal Navy warships destroyed numerous shore batteries and Chinese warships, laying waste to several coastal forts along the way. Eventually, they pushed their way up north close enough to threaten the Imperial Palace in Beijing itself.[15]

The China Navigation Company was an early shipping company founded in 1876 in London, initially to trade up the Yangtze River from their Shanghai base with passengers and cargo. Chinese coastal trade started shortly after, and in 1883 a regular service to Australia was initiated.[15]

Yangtze River steam boats filmed in 1937 USS Luzon

USS Luzon

Cruise boats on Yangtze

Cruise boats on Yangtze A vehicle carrier on Yangtze

A vehicle carrier on Yangtze A container carrier on Yangtze

A container carrier on YangtzeSteamers came late to the upper river, the section stretching from Yichang to Chongqing. Freshets from Himalayan snowmelt created treacherous seasonal currents. But summer was better navigationally and the three gorges, described as a "150-mile passage which is like the narrow throat of an hourglass," posed hazardous threats of crosscurrents, whirlpools and eddies, creating significant challenges to steamship efforts. Furthermore, Chongqing is 700 – 800 feet above sea level, requiring powerful engines to make the upriver climb. Junk travel accomplished the upriver feat by employing 70–80 trackers, men hitched to hawsers who physically pulled ships upriver through some of the most risky and deadly sections of the three gorges.[17] Archibald John Little took an interest in Upper Yangtze navigation when in 1876, the Chefoo Convention opened Chongqing to consular residence but stipulated that foreign trade might only commence once steamships had succeeded in ascending the river to that point. Little formed the Upper Yangtze Steam Navigation Co., Ltd. and built Kuling but his attempts to take the vessel further upriver than Yichang were thwarted by the Chinese authorities who were concerned about the potential loss of transit duties, competition to their native junk trade and physical damage to their crafts caused by steamship wakes. Kuling was sold to China Merchants Steam Navigation Company for lower river service. In 1890, the Chinese government agreed to open Chongqing to foreign trade as long as it was restricted to native crafts. In 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki provided a provision which opened Chongqing fully to foreign trade. Little took up residence in Chongqing and built Leechuan, to tackle the gorges in 1898. In March Leechuan completed the upriver journey to Chongqing but not without the assistance of trackers. Leechuan was not designed for cargo or passengers and if Little wanted to take his vision one step further, he required an expert pilot.[18] In 1898, Little persuaded Captain Samuel Cornell Plant to come out to China to lend his expertise. Captain Plant had just completed navigation of Persia's Upper Karun River and took up Little's offer to assess the Upper Yangtze on Leechuan at the end of 1898. With Plant's design input, Little had SS Pioneer built with Plant in command. In June 1900, Plant was the first to successfully pilot a merchant steamer on the Upper Yangtze from Yichang to Chongqing. Pioneer was sold to Royal Navy after its first run due to threat from the Boxer Rebellion and renamed HMS Kinsha. Germany's steamship effort that same year on SS Suixing ended in catastrophe. On Suixing's maiden voyage, the vessel hit a rock and sunk, killing its captain and ending realistic hopes of regular commercial steam service on the Upper Yangtze. In 1908, local Sichuan merchants and their government partnered with Captain Plant to form Sichuan Steam Navigation Company becoming the first successful service between Yichang and Chongqing. Captain Plant designed and commanded its two ships, SS Shutung and SS Shuhun. Other Chinese vessels came onto the run and by 1915, foreign ships expressed their interest too. Plant was appointed by Chinese Maritime Customs Service as First Senior River Inspector in 1915. In this role, Plant installed navigational marks and established signaling systems. He also wrote Handbook for the Guidance of Shipmasters on the Ichang-Chungking Section of the Yangtze River, a detailed and illustrated account of the Upper Yangtze's currents, rocks, and other hazards with navigational instruction. Plant trained hundreds of Chinese and foreign pilots and issued licenses and worked with the Chinese government to make the river safer in 1917 by removing some of the most difficult obstacles and threats with explosives. In August 1917, British Asiatic Petroleum became the first foreign merchant steamship on the Upper Yangtze. Commercial firms, Robert Dollar Company, Jardine Matheson, Butterfield and Swire and Standard Oil added their own steamers on the river between 1917 and 1919. Between 1918 and 1919, Sichuan warlord violence and escalating civil war put Sichuan Steam Navigational Company out of business.[19] Shutung was commandeered by warlords and Shuhun was brought down river to Shanghai for safekeeping.[20] In 1921, when Captain Plant died at sea while returning home to England, a Plant Memorial Fund was established to perpetuate Plant's name and contributions to Upper Yangtze navigation. The largest shipping companies in service, Butterfield & Swire, Jardine Matheson, Standard Oil, Mackenzie & Co., Asiatic Petroleum, Robert Dollar, China Merchants S.N. Co. and British-American Tobacco Co., contributed alongside international friends and Chinese pilots. In 1924, a 50-foot granite pyramidal obelisk was erected in Xintan, on the site of Captain Plant's home, in a Chinese community of pilots and junk owners. One face of the monument is inscribed in Chinese and another in English. Though recently relocated to higher ground ahead of the Three Gorges Dam, the monument still stands overlooking the Upper Yangtze River near Yichang, a rare collective tribute to a westerner in China.[21][22]

Standard Oil ran the tankers Mei Ping, Mei An and Mei Hsia, which were collectively destroyed on December 12, 1937, when Japanese warplanes bombed and sank the U.S.S. Panay. One of the Standard Oil captains who survived this attack had served on the Upper River for 14 years.[23]

The Imperial Japanese Navy armored cruiser Izumo in Shanghai in 1937. She sank riverboats on the Yangtze in 1941.

Contemporary events

The Imperial Japanese Navy armored cruiser Izumo in Shanghai in 1937. She sank riverboats on the Yangtze in 1941.

Contemporary events

Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong took staged swims in the river in 1956 and 1966 at Wuhan in publicity stunts to demonstrate his health, also starting a swimming craze through party propaganda.[24][25]

In August 2019, Welsh adventurer Ash Dykes became the first person to complete the 4,000-mile (6,437 km) trek along the course of the river, walking for 352 days from its source to its mouth.[26]

Add new comment