Ecuador

Context of Ecuador

Ecuador ( (listen) EK-wə-dor; Spanish pronunciation: [ekwaˈðoɾ] (listen); Quechua: Ikwayur; Shuar: Ecuador or Ekuatur), officially the Republic of Ecuador (Spanish: República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: Ikwadur Ripuwlika; Shuar: Ekuatur Nunka), is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. Ecuador also includes the Galápagos Islands in the Pacific, about 1,000 kilometers (621 ...Read more

Ecuador ( (listen) EK-wə-dor; Spanish pronunciation: [ekwaˈðoɾ] (listen); Quechua: Ikwayur; Shuar: Ecuador or Ekuatur), officially the Republic of Ecuador (Spanish: República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: Ikwadur Ripuwlika; Shuar: Ekuatur Nunka), is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. Ecuador also includes the Galápagos Islands in the Pacific, about 1,000 kilometers (621 mi) west of the mainland. The country's capital and largest city is Quito.

The territories of modern-day Ecuador were once home to a variety of Indigenous groups that were gradually incorporated into the Inca Empire during the 15th century. The territory was colonized by Spain during the 16th century, achieving independence in 1820 as part of Gran Colombia, from which it emerged as its own sovereign state in 1830. The legacy of both empires is reflected in Ecuador's ethnically diverse population, with most of its 17.8 million people being mestizos, followed by large minorities of Europeans, Native American, African, and Asian descendants. Spanish is the official language and is spoken by a majority of the population, though 13 Native languages are also recognized, including Quechua and Shuar.

The sovereign state of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic and a developing country whose economy is highly dependent on exports of commodities, namely petroleum and agricultural products. It is governed as a democratic presidential republic. The country is a founding member of the United Nations, Organization of American States, Mercosur, PROSUR, and the Non-Aligned Movement.

One of 17 megadiverse countries in the world, Ecuador hosts many endemic plants and animals, such as those of the Galápagos Islands. In recognition of its unique ecological heritage, the new constitution of 2008 is the first in the world to recognize legally enforceable Rights of Nature, or ecosystem rights.

According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, between 2006 and 2016, poverty decreased from 36.7% to 22.5% and annual per capita GDP growth was 1.5 percent (as compared to 0.6 percent over the prior two decades). At the same time, the country's Gini index of economic inequality decreased from 0.55 to 0.47.

More about Ecuador

- Currency United States dollar

- Calling code +593

- Internet domain .ec

- Mains voltage 120V/60Hz

- Democracy index 6.13

- Population 16938986

- Area 255586

- Driving side right

- Read lessThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020)Pre-Inca era

Tumaco-La Tolita mythological figure in feathered costume. Between 100 BC and 100 AD. Found in Esmeraldas

Tumaco-La Tolita mythological figure in feathered costume. Between 100 BC and 100 AD. Found in EsmeraldasVarious peoples had settled in the area of future Ecuador before the arrival of the Incas. The archeological evidence suggests that the Paleo-Indians' first dispersal into the Americas occurred near the end of the last glacial period, around 16,500–13,000 years ago. The first people who reached Ecuador may have journeyed by land from North and Central America or by boat down the Pacific Ocean coastline.

Even though their languages were unrelated, these groups developed similar groups of cultures, each based in different environments. The people of the coast combined agriculture with fishing, hunting, and gathering; the people of the highland Andes developed a sedentary agricultural way of life; and peoples of the Amazon basin relied on hunting and gathering, in some cases combined with agriculture and arboriculture.

Over time these groups began to interact and intermingle with each other so that groups of families in one area became one community or tribe, with a similar language and culture. Many civilizations[1] arose in Ecuador, such as the Valdivia Culture and Machalilla Culture on the coast,[2][3] the Quitus (near present-day Quito),[4] and the Cañari (near present-day Cuenca).[5] Each civilization developed its own distinctive architecture, pottery, and religious interests.[citation needed]

In the highland Andes mountains, where life was more sedentary, groups of tribes cooperated and formed villages; thus the first nations based on agricultural resources and the domestication of animals formed. Eventually, through wars and marriage alliances of their leaders, groups of nations formed confederations. The region around the country's modern capital, Quito, consolidated under a confederation called the Shyris, which exercised organized trading and bartering between the different regions.

Inca era Ruins of Ingapirca, this site served as an outpost and provisioning of the Incan troops, but mainly it was a place of worship and veneration to the sun, the supreme Inca God, thus constituting a Coricancha, dedicated to the Inca ritual.

Ruins of Ingapirca, this site served as an outpost and provisioning of the Incan troops, but mainly it was a place of worship and veneration to the sun, the supreme Inca God, thus constituting a Coricancha, dedicated to the Inca ritual. Pre-Columbian shrunken head of the Shuars (Jivaroan peoples).

Pre-Columbian shrunken head of the Shuars (Jivaroan peoples).When the Incas arrived, they found that these confederations were so developed that it took the Incas two generations of rulers—Topa Inca Yupanqui and Huayna Capac—to absorb them into the Inca Empire. People belonging to the confederations that gave them the most problems were deported to distant areas of Peru, Bolivia, and north Argentina. Similarly, a number of loyal Inca subjects from Peru and Bolivia were brought to Ecuador to prevent rebellion. Thus, the region of highland Ecuador became part of the Inca Empire in 1463 sharing the same language.

In contrast, when the Incas made incursions into coastal Ecuador and the eastern Amazon jungles of Ecuador, they found both the environment and indigenous people more hostile. Moreover, when the Incas tried to subdue them, these indigenous people withdrew to the interior and resorted to guerrilla tactics. As a result, Inca expansion into the Amazon Basin and the Pacific coast of Ecuador was hampered. The indigenous people of the Amazon jungle and coastal Ecuador remained relatively autonomous until the Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived in force. The Amazonian people and the Cayapas of Coastal Ecuador were the only groups to resist both Inca and Spanish domination, maintaining their languages and cultures well into the 21st century.

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Inca Empire was involved in a civil war. The untimely death of both the heir Ninan Cuchi and the Emperor Huayna Capac, from a European disease that spread into Ecuador, created a power vacuum between two factions. The northern faction headed by Atahualpa claimed that Huayna Capac gave a verbal decree before his death about how the empire should be divided. He gave the territories pertaining to present-day Ecuador and northern Peru to his favorite son Atahualpa, who was to rule from Quito; and he gave the rest to Huáscar, who was to rule from Cuzco. He willed that his heart be buried in Quito, his favorite city, and the rest of his body be buried with his ancestors in Cuzco.

Huáscar did not recognize his father's will, since it did not follow Inca traditions of naming an Inca through the priests. Huáscar ordered Atahualpa to attend their father's burial in Cuzco and pay homage to him as the new Inca ruler. Atahualpa, with a large number of his father's veteran soldiers, decided to ignore Huáscar, and a civil war ensued. A number of bloody battles took place until finally Huáscar was captured. Atahualpa marched south to Cuzco and massacred the royal family associated with his brother.

In 1532, a small band of Spaniards headed by Francisco Pizarro landed in Tumbez and marched over the Andes Mountains until they reached Cajamarca, where the new Inca Atahualpa was to hold an interview with them. Valverde, the priest, tried to convince Atahualpa that he should join the Catholic Church and declare himself a vassal of Spain. This infuriated Atahualpa so much that he threw the Bible to the ground. At this point the enraged Spaniards, with orders from Valverde, attacked and massacred unarmed escorts of the Inca and captured Atahualpa. Pizarro promised to release Atahualpa if he made good his promise of filling a room full of gold. But, after a mock trial, the Spaniards executed Atahualpa by strangulation.

Spanish colonization Major square of Quito. Painting of 18th century. Quito Painting Colonial School.

Major square of Quito. Painting of 18th century. Quito Painting Colonial School.New infectious diseases such as smallpox, endemic to the Europeans, caused high fatalities among the Amerindian population during the first decades of Spanish rule, as they had no immunity. At the same time, the natives were forced into the encomienda labor system for the Spanish. In 1563, Quito became the seat of a real audiencia (administrative district) of Spain and part of the Viceroyalty of Peru and later the Viceroyalty of New Granada.

The 1797 Riobamba earthquake, which caused up to 40,000 casualties, was studied by Alexander von Humboldt, when he visited the area in 1801–1802.[6]

After nearly 300 years of Spanish rule, Quito still remained small with a population of 10,000 people. On 10 August 1809, the city's criollos called for independence from Spain (first among the peoples of Latin America). They were led by Juan Pío Montúfar, Quiroga, Salinas, and Bishop Cuero y Caicedo. Quito's nickname, "Luz de América" ("Light of America"), is based on its leading role in trying to secure an independent, local government. Although the new government lasted no more than two months, it had important repercussions and was an inspiration for the independence movement of the rest of Spanish America. Today, 10 August is celebrated as Independence Day, a national holiday.[7]

IndependenceVenezuelan independence leader Antonio José de Sucre The "Guayaquil Conference" was the meeting between the two main Spanish South American independence leaders. In it the form of government of the nascent countries was discussed, San Martín opted for a unified South America in the form of a monarchy, while Bolívar opted for the same but into a republic. 1843 painting.

The "Guayaquil Conference" was the meeting between the two main Spanish South American independence leaders. In it the form of government of the nascent countries was discussed, San Martín opted for a unified South America in the form of a monarchy, while Bolívar opted for the same but into a republic. 1843 painting.On 9 October 1820, the Department of Guayaquil became the first territory in Ecuador to gain its independence from Spain, and it spawned most of the Ecuadorian coastal provinces, establishing itself as an independent state. Its inhabitants celebrated what is now Ecuador's official Independence Day on 24 May 1822. The rest of Ecuador gained its independence after Antonio José de Sucre defeated the Spanish Royalist forces at the Battle of Pichincha, near Quito. Following the battle, Ecuador joined Simón Bolívar's Republic of Gran Colombia, also including modern-day Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama. In 1830, Ecuador separated from Gran Colombia and became an independent republic. Two years later, it annexed the Galapagos Islands.[8]

The 19th century was marked by instability for Ecuador with a rapid succession of rulers. The first president of Ecuador was the Venezuelan-born Juan José Flores, who was ultimately deposed. Leaders who followed him included Vicente Rocafuerte; José Joaquín de Olmedo; José María Urbina; Diego Noboa; Pedro José de Arteta; Manuel de Ascásubi; and Flores's own son, Antonio Flores Jijón, among others. The conservative Gabriel García Moreno unified the country in the 1860s with the support of the Roman Catholic Church. In the late 19th century, world demand for cocoa tied the economy to commodity exports and led to migrations from the highlands to the agricultural frontier on the coast.

Ecuador abolished slavery in 1851.[9] The descendants of enslaved Ecuadorians are among today's Afro-Ecuadorian population.

Liberal Revolution Antique dug out canoes in the courtyard of the Old Military Hospital in the Historic Center of Quito

Antique dug out canoes in the courtyard of the Old Military Hospital in the Historic Center of QuitoThe Liberal Revolution of 1895 under Eloy Alfaro reduced the power of the clergy and the conservative land owners. This liberal wing retained power until the military "Julian Revolution" of 1925. The 1930s and 1940s were marked by instability and emergence of populist politicians, such as five-time President José María Velasco Ibarra.

Loss of claimed territories since 1830 President Juan José Flores de jure territorial claimsAfter Ecuador's separation from Colombia on 13 May 1830, its first President, General Juan José Flores, laid claim to the territory that had belonged to the Real Audiencia of Quito, also referred to as the Presidencia of Quito. He supported his claims with Spanish Royal decrees, or real cedulas, that delineated the borders of Spain's former overseas colonies. In the case of Ecuador, Flores based Ecuador's de jure claims on the Real Cedulas of 1563, 1739, and 1740; with modifications in the Amazon Basin and Andes Mountains that were introduced through the Treaty of Guayaquil (1829) which Peru reluctantly signed, after the overwhelmingly outnumbered Gran Colombian force led by Antonio José de Sucre defeated President and General La Mar's Peruvian invasion force in the Battle of Tarqui. In addition, Ecuador's eastern border with the Portuguese colony of Brazil in the Amazon Basin was modified before the Wars of Independence by the First Treaty of San Ildefonso (1777) between the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. Moreover, to add legitimacy to his claims, on 16 February 1840, Flores signed a treaty with Spain, whereby Flores convinced Spain to officially recognize Ecuadorian independence and its sole rights to colonial titles over Spain's former colonial territory known anciently to Spain as the Kingdom and Presidency of Quito.

Ecuador during its long and turbulent history has lost most of its contested territories to each of its more powerful neighbors, such as Colombia in 1832 and 1916, Brazil in 1904 through a series of peaceful treaties, and Peru after a short war in which the Protocol of Rio de Janeiro was signed in 1942.

Struggle for independenceDuring the struggle for independence, before Peru or Ecuador became independent nations, a few areas of the former Vice Royalty of New Granada – Guayaquil, Tumbez, and Jaén – declared themselves independent from Spain. A few months later, a part of the Peruvian liberation army of San Martin decided to occupy the independent cities of Tumbez and Jaén with the intention of using these towns as springboards to occupy the independent city of Guayaquil and then to liberate the rest of the Audiencia de Quito (Ecuador). It was common knowledge among the top officers of the liberation army from the south that their leader San Martin wished to liberate present-day Ecuador and add it to the future republic of Peru, since it had been part of the Inca Empire before the Spaniards conquered it.

However, Bolívar's intention was to form a new republic known as the Gran Colombia, out of the liberated Spanish territory of New Granada which consisted of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. San Martin's plans were thwarted when Bolívar, with the help of Marshal Antonio José de Sucre and the Gran Colombian liberation force, descended from the Andes mountains and occupied Guayaquil; they also annexed the newly liberated Audiencia de Quito to the Republic of Gran Colombia. This happened a few days before San Martin's Peruvian forces could arrive and occupy Guayaquil, with the intention of annexing Guayaquil to the rest of Audiencia of Quito (Ecuador) and to the future republic of Peru. Historic documents repeatedly stated that San Martin told Bolivar he came to Guayaquil to liberate the land of the Incas from Spain. Bolivar countered by sending a message from Guayaquil welcoming San Martin and his troops to Colombian soil.

Peruvian occupation of Jaén, Tumbes, and GuayaquilIn the south, Ecuador had de jure claims to a small piece of land beside the Pacific Ocean known as Tumbes which lay between the Zarumilla and Tumbes rivers. In Ecuador's southern Andes Mountain region where the Marañon cuts across, Ecuador had de jure claims to an area it called Jaén de Bracamoros. These areas were included as part of the territory of Gran Colombia by Bolivar on 17 December 1819, during the Congress of Angostura when the Republic of Gran Colombia was created. Tumbes declared itself independent from Spain on 17 January 1821, and Jaen de Bracamoros on 17 June 1821, without any outside help from revolutionary armies. However, that same year, 1821, Peruvian forces participating in the Trujillo revolution occupied both Jaen and Tumbes. Some Peruvian generals, without any legal titles backing them up and with Ecuador still federated with the Gran Colombia, had the desire to annex Ecuador to the Republic of Peru at the expense of the Gran Colombia, feeling that Ecuador was once part of the Inca Empire.

On 28 July 1821, Peruvian independence was proclaimed in Lima by the Liberator San Martin, and Tumbes and Jaen, which were included as part of the revolution of Trujillo by the Peruvian occupying force, had the whole region swear allegiance to the new Peruvian flag and incorporated itself into Peru, even though Peru was not completely liberated from Spain. After Peru was completely liberated from Spain by the patriot armies led by Bolivar and Antonio Jose de Sucre at the Battle of Ayacucho dated 9 December 1824, there was a strong desire by some Peruvians to resurrect the Inca Empire and to include Bolivia and Ecuador. One of these Peruvian Generals was the Ecuadorian-born José de La Mar, who became one of Peru's presidents after Bolivar resigned as dictator of Peru and returned to Colombia. Gran Colombia had always protested Peru for the return of Jaen and Tumbes for almost a decade, then finally Bolivar after long and futile discussion over the return of Jaen, Tumbes, and part of Mainas, declared war. President and General José de La Mar, who was born in Ecuador, believing his opportunity had come to annex the District of Ecuador to Peru, personally, with a Peruvian force, invaded and occupied Guayaquil and a few cities in the Loja region of southern Ecuador on 28 November 1828.

The war ended when a triumphant heavily outnumbered southern Gran Colombian army at Battle of Tarqui dated 27 February 1829, led by Antonio José de Sucre, defeated the Peruvian invasion force led by President La Mar. This defeat led to the signing of the Treaty of Guayaquil dated 22 September 1829, whereby Peru and its Congress recognized Gran Colombian rights over Tumbes, Jaen, and Maynas. Through protocolized meetings between representatives of Peru and Gran Colombia, the border was set as Tumbes river in the west and in the east the Maranon and Amazon rivers were to be followed toward Brazil as the most natural borders between them. However, what was pending was whether the new border around the Jaen region should follow the Chinchipe River or the Huancabamba River. According to the peace negotiations Peru agreed to return Guayaquil, Tumbez, and Jaén; despite this, Peru returned Guayaquil, but failed to return Tumbes and Jaén, alleging that it was not obligated to follow the agreements, since the Gran Colombia ceased to exist when it divided itself into three different nations – Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela.

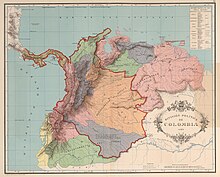

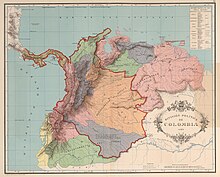

The dissolution of Gran Colombia Map of the former Gran Colombia in 1824 (named in its time as Colombia), the Gran Colombia covered all the colored region.

Map of the former Gran Colombia in 1824 (named in its time as Colombia), the Gran Colombia covered all the colored region. Ecuador in 1832

Ecuador in 1832The Central District of the Gran Colombia, known as Cundinamarca or New Granada (modern Colombia) with its capital in Bogota, did not recognize the separation of the Southern District of the Gran Colombia, with its capital in Quito, from the Gran Colombian federation on 13 May 1830. After Ecuador's separation, the Department of Cauca voluntarily decided to unite itself with Ecuador due to instability in the central government of Bogota. The Venezuelan born President of Ecuador, the general Juan José Flores, with the approval of the Ecuadorian congress annexed the Department of Cauca on 20 December 1830, since the government of Cauca had called for union with the District of the South as far back as April 1830. Moreover, the Cauca region, throughout its long history, had very strong economic and cultural ties with the people of Ecuador. Also, the Cauca region, which included such cities as Pasto, Popayán, and Buenaventura, had always been dependent on the Presidencia or Audiencia of Quito.

Fruitless negotiations continued between the governments of Bogotá and Quito, where the government of Bogotá did not recognize the separation of Ecuador or that of Cauca from the Gran Colombia until war broke out in May 1832. In five months, New Granada defeated Ecuador due to the fact that the majority of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces were composed of rebellious angry unpaid veterans from Venezuela and Colombia that did not want to fight against their fellow countrymen. Seeing that his officers were rebelling, mutinying, and changing sides, President Flores had no option but to reluctantly make peace with New Granada. The Treaty of Pasto of 1832 was signed by which the Department of Cauca was turned over to New Granada (modern Colombia), the government of Bogotá recognized Ecuador as an independent country and the border was to follow the Ley de División Territorial de la República de Colombia (Law of the Division of Territory of the Gran Colombia) passed on 25 June 1824. This law set the border at the river Carchi and the eastern border that stretched to Brazil at the Caquetá river. Later, Ecuador contended that the Republic of Colombia, while reorganizing its government, unlawfully made its eastern border provisional and that Colombia extended its claims south to the Napo River because it said that the Government of Popayán extended its control all the way to the Napo River.

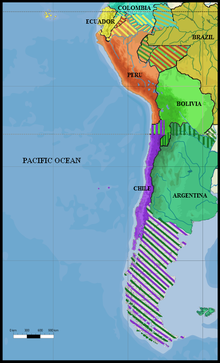

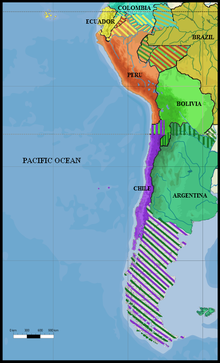

Struggle for possession of the Amazon Basin South America (1879): All land claims by Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia in 1879

South America (1879): All land claims by Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia in 1879When Ecuador seceded from the Gran Colombia, Peru decided not to follow the treaty of Guayaquil of 1829 or the protocoled agreements made. Peru contested Ecuador's claims with the newly discovered Real Cedula of 1802, by which Peru claims the King of Spain had transferred these lands from the Viceroyalty of New Granada to the Viceroyalty of Peru. During colonial times this was to halt the ever-expanding Portuguese settlements into Spanish domains, which were left vacant and in disorder after the expulsion of Jesuit missionaries from their bases along the Amazon Basin. Ecuador countered by labeling the Cedula of 1802 an ecclesiastical instrument, which had nothing to do with political borders. Peru began its de facto occupation of disputed Amazonian territories, after it signed a secret 1851 peace treaty in favor of Brazil. This treaty disregarded Spanish rights that were confirmed during colonial times by a Spanish-Portuguese treaty over the Amazon regarding territories held by illegal Portuguese settlers.

Peru began occupying the missionary villages in the Mainas or Maynas region, which it began calling Loreto, with its capital in Iquitos. During its negotiations with Brazil, Peru claimed Amazonian Basin territories up to Caqueta River in the north and toward the Andes Mountain range. Colombia protested stating that its claims extended south toward the Napo and Amazon Rivers. Ecuador protested that it claimed the Amazon Basin between the Caqueta river and the Marañon-Amazon river. Peru ignored these protests and created the Department of Loreto in 1853 with its capital in Iquitos. Peru briefly occupied Guayaquil again in 1860, since Peru thought that Ecuador was selling some of the disputed land for development to British bond holders, but returned Guayaquil after a few months. The border dispute was then submitted to Spain for arbitration from 1880 to 1910, but to no avail.[10]

In the early part of the 20th century, Ecuador made an effort to peacefully define its eastern Amazonian borders with its neighbours through negotiation. On 6 May 1904, Ecuador signed the Tobar-Rio Branco Treaty recognizing Brazil's claims to the Amazon in recognition of Ecuador's claim to be an Amazonian country to counter Peru's earlier Treaty with Brazil back on 23 October 1851. Then after a few meetings with the Colombian government's representatives an agreement was reached and the Muñoz Vernaza-Suarez Treaty was signed 15 July 1916, in which Colombian rights to the Putumayo river were recognized as well as Ecuador's rights to the Napo river and the new border was a line that ran midpoint between those two rivers. In this way, Ecuador gave up the claims it had to the Amazonian territories between the Caquetá River and Napo River to Colombia, thus cutting itself off from Brazil. Later, a brief war erupted between Colombia and Peru, over Peru's claims to the Caquetá region, which ended with Peru reluctantly signing the Salomon-Lozano Treaty on 24 March 1922. Ecuador protested this secret treaty, since Colombia gave away Ecuadorian claimed land to Peru that Ecuador had given to Colombia in 1916.

On 21 July 1924, the Ponce-Castro Oyanguren Protocol was signed between Ecuador and Peru where both agreed to hold direct negotiations and to resolve the dispute in an equitable manner and to submit the differing points of the dispute to the United States for arbitration. Negotiations between the Ecuadorian and Peruvian representatives began in Washington on 30 September 1935. These negotiations were long and tiresome. Both sides logically presented their cases, but no one seemed to give up their claims. Then on 6 February 1937, Ecuador presented a transactional line which Peru rejected the next day. The negotiations turned into intense arguments during the next 7 months and finally on 29 September 1937, the Peruvian representatives decided to break off the negotiations without submitting the dispute to arbitration because the direct negotiations were going nowhere.[citation needed]

Four years later in 1941, amid fast-growing tensions within disputed territories around the Zarumilla River, war broke out with Peru. Peru claimed that Ecuador's military presence in Peruvian-claimed territory was an invasion; Ecuador, for its part, claimed that Peru had recently invaded Ecuador around the Zarumilla River and that Peru since Ecuador's independence from Spain has systematically occupied Tumbez, Jaen, and most of the disputed territories in the Amazonian Basin between the Putomayo and Marañon Rivers. In July 1941, troops were mobilized in both countries. Peru had an army of 11,681 troops who faced a poorly supplied and inadequately armed Ecuadorian force of 2,300, of which only 1,300 were deployed in the southern provinces. Hostilities erupted on 5 July 1941, when Peruvian forces crossed the Zarumilla river at several locations, testing the strength and resolve of the Ecuadorian border troops. Finally, on 23 July 1941, the Peruvians launched a major invasion, crossing the Zarumilla river in force and advancing into the Ecuadorian province of El Oro.

Map of Ecuadorian land claims after 1916

Map of Ecuadorian land claims after 1916During the course of the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War, Peru gained control over part of the disputed territory and some parts of the province of El Oro, and some parts of the province of Loja, demanding that the Ecuadorian government give up its territorial claims. The Peruvian Navy blocked the port of Guayaquil, almost cutting all supplies to the Ecuadorian troops. After a few weeks of war and under pressure by the United States and several Latin American nations, all fighting came to a stop. Ecuador and Peru came to an accord formalized in the Rio Protocol, signed on 29 January 1942, in favor of hemispheric unity against the Axis Powers in World War II favoring Peru with the territory they occupied at the time the war came to an end.

The 1944 Glorious May Revolution followed a military-civilian rebellion and a subsequent civic strike which successfully removed Carlos Arroyo del Río as a dictator from Ecuador's government. However, a post-Second World War recession and popular unrest led to a return to populist politics and domestic military interventions in the 1960s, while foreign companies developed oil resources in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In 1972, construction of the Andean pipeline was completed. The pipeline brought oil from the east side of the Andes to the coast, making Ecuador South America's second largest oil exporter. The pipeline in southern Ecuador did nothing to resolve tensions between Ecuador and Peru, however.

In 1978, the city of Quito and the Galápagos Islands were inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, making the first two properties in the world to become listed sites.

Ecuadorian troops during the Cenepa WarThe Mirage F.1JA (FAE-806) was one aircraft involved in the claimed shooting down of two Peruvian Sukhoi Su-22 on 10 February 1995.The Rio Protocol failed to precisely resolve the border along a little river in the remote Cordillera del Cóndor region in southern Ecuador. This caused a long-simmering dispute between Ecuador and Peru, which ultimately led to fighting between the two countries; first a border skirmish in January–February 1981 known as the Paquisha Incident, and ultimately full-scale warfare in January 1995 where the Ecuadorian military shot down Peruvian aircraft and helicopters and Peruvian infantry marched into southern Ecuador. Each country blamed the other for the onset of hostilities, known as the Cenepa War. Sixto Durán Ballén, the Ecuadorian president, famously declared that he would not give up a single centimeter of Ecuador. Popular sentiment in Ecuador became strongly nationalistic against Peru: graffiti could be seen on the walls of Quito referring to Peru as the "Cain de Latinoamérica", a reference to the murder of Abel by his brother Cain in the Book of Genesis.[11]

Ecuador and Peru signed the Brasilia Presidential Act peace agreement on 26 October 1998, which ended hostilities, and effectively put an end to the Western Hemisphere's longest running territorial dispute.[12] The Guarantors of the Rio Protocol (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and the United States of America) ruled that the border of the undelineated zone was to be set at the line of the Cordillera del Cóndor. While Ecuador had to give up its decades-old territorial claims to the eastern slopes of the Cordillera, as well as to the entire western area of Cenepa headwaters, Peru was compelled to give to Ecuador, in perpetual lease but without sovereignty, 1 km2 (0.39 sq mi) of its territory, in the area where the Ecuadorian base of Tiwinza – focal point of the war – had been located within Peruvian soil and which the Ecuadorian Army held during the conflict. The final border demarcation came into effect on 13 May 1999, and the multi-national MOMEP (Military Observer Mission for Ecuador and Peru) troop deployment withdrew on 17 June 1999.[12]

Military governments (1972–79)In 1972, a "revolutionary and nationalist" military junta overthrew the government of Velasco Ibarra. The coup d'état was led by General Guillermo Rodríguez and executed by navy commander Jorge Queirolo G. The new president exiled José María Velasco to Argentina. He remained in power until 1976, when he was removed by another military government. That military junta was led by Admiral Alfredo Poveda, who was declared chairman of the Supreme Council. The Supreme Council included two other members: General Guillermo Durán Arcentales and General Luis Pintado. The civil society more and more insistently called for democratic elections. Colonel Richelieu Levoyer, Government Minister, proposed and implemented a Plan to return to the constitutional system through universal elections. This plan enabled the new democratically elected president to assume the duties of the executive office.

Return to democracyElections were held on 29 April 1979, under a new constitution. Jaime Roldós Aguilera was elected president, garnering over one million votes, the most in Ecuadorian history. He took office on 10 August, as the first constitutionally elected president after nearly a decade of civilian and military dictatorships. In 1980, he founded the Partido Pueblo, Cambio y Democracia (People, Change, and Democracy Party) after withdrawing from the Concentración de Fuerzas Populares (Popular Forces Concentration) and governed until 24 May 1981, when he died along with his wife and the minister of defense, Marco Subia Martinez, when his Air Force plane crashed in heavy rain near the Peruvian border. Many people believe that he was assassinated by the CIA,[13] given the multiple death threats leveled against him because of his reformist agenda, deaths in automobile crashes of two key witnesses before they could testify during the investigation, and the sometimes contradictory accounts of the incident.

Roldos was immediately succeeded by Vice President Osvaldo Hurtado, who was followed in 1984 by León Febres Cordero from the Social Christian Party. Rodrigo Borja Cevallos of the Democratic Left (Izquierda Democrática, or ID) party won the presidency in 1988, running in the runoff election against Abdalá Bucaram (brother in law of Jaime Roldos and founder of the Ecuadorian Roldosist Party). His government was committed to improving human rights protection and carried out some reforms, notably an opening of Ecuador to foreign trade. The Borja government concluded an accord leading to the disbanding of the small terrorist group, "¡Alfaro Vive, Carajo!" ("Alfaro Lives, Dammit!"), named after Eloy Alfaro. However, continuing economic problems undermined the popularity of the ID, and opposition parties gained control of Congress in 1999.

President Lenín Moreno, first lady Rocío González Navas and his predecessor Rafael Correa, 3 April 2017

President Lenín Moreno, first lady Rocío González Navas and his predecessor Rafael Correa, 3 April 2017A notable event was the Cenepa War fought between Ecuador and Peru in 1995.

Ecuador adopted the United States dollar on 13 April 2000 as its national currency and on 11 September, the country eliminated the Ecuadorian sucre, in order to stabilize the country's economy.[14] The US Dollar has been the only official currency of Ecuador since the year 2000.[15]

The emergence of the Amerindian population as an active constituency has added to the democratic volatility of the country in recent years. The population has been motivated by government failures to deliver on promises of land reform, lower unemployment and provision of social services, and historical exploitation by the land-holding elite. Their movement, along with the continuing destabilizing efforts by both the elite and leftist movements, has led to a deterioration of the executive office. The populace and the other branches of government give the president very little political capital, as illustrated by the most recent removal of President Lucio Gutiérrez from office by Congress in April 2005.[16] Vice President Alfredo Palacio took his place[17] and remained in office until the presidential election of 2006, in which Rafael Correa gained the presidency.[18] On 15 January 2007, Rafael Correa was sworn in as the President of Ecuador. Several left-wing political leaders of Latin America, his future allies, attended the ceremony.[19]

The new socialist constitution, endorsed in 2008 referendum (2008 Constitution of Ecuador), implemented leftist reforms.[20] In December 2008, president Correa declared Ecuador's national debt illegitimate, based on the argument that it was odious debt contracted by corrupt and despotic prior regimes. He announced that the country would default on over $3 billion worth of bonds; he then pledged to fight creditors in international courts and succeeded in reducing the price of outstanding bonds by more than 60%.[21] He brought Ecuador into the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas in June 2009. Correa's administration succeeded in reducing the high levels of poverty and unemployment in Ecuador.[22][23][24][25][26]

After Correa eraRafael Correa's three consecutive terms (from 2007 to 2017) were followed by his former Vice President Lenín Moreno’s four years as president (2017–21). After being elected in 2017, President Lenin Moreno's government adopted economically liberal policies: reduction of public spending, trade liberalization, flexibility of the labour code, etc. Ecuador also left the left-wing Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (Alba) in August 2018.[27] The Productive Development Act enshrines an austerity policy, and reduces the development and redistribution policies of the previous mandate. In the area of taxes, the authorities aim to "encourage the return of investors" by granting amnesty to fraudsters and proposing measures to reduce tax rates for large companies. In addition, the government waives the right to tax increases in raw material prices and foreign exchange repatriations.[28] In October 2018, the government of President Lenin Moreno cut diplomatic relations with the Maduro administration of Venezuela, a close ally of Rafael Correa.[29] The relations with the United States improved significantly during the presidency of Lenin Moreno. In February 2020, his visit to Washington was the first meeting between an Ecuadorian and U.S. president in 17 years.[30] In June 2019, Ecuador had agreed to allow US military planes to operate from an airport on the Galapagos Islands.[31]

2019 state of emergencyA series of protests began on 3 October 2019 against the end of fuel subsidies and austerity measures adopted by President of Ecuador Lenín Moreno and his administration. On 10 October, protesters overran the capital Quito causing the Government of Ecuador to relocate to Guayaquil,[32] but the government had plans to return to Quito.[33] On 14 October 2019, the government restored fuel subsidies and withdrew an austerity package, meaning the end of nearly two weeks of protests.[34]

Presidency of Guillermo Lasso since 2021The 11 April 2021 election run-off vote ended in a win for conservative former banker, Guillermo Lasso, taking 52.4% of the vote compared to 47.6% of left-wing economist Andrés Arauz, supported by exiled former president, Rafael Correa. Previously, President-elect Lasso finished second in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections.[35] On 24 May 2021, Guillermo Lasso was sworn in as the new President of Ecuador, becoming the country's first right-wing leader in 14 years.[36] However, President Lasso's party CREO Movement, and its ally the Social Christian Party (PSC) secured only 31 parliamentary seats out of 137, while the Union for Hope (UNES) of Andrés Arauz was the strongest parliamentary group with 49 seats, meaning the new president needs support from Izquierda Democrática (18 seats) and the indigenist Pachakutik (27 seats) to push through his legislative agenda.[37]

In October 2021, President Lasso declared a 60-day state of emergency with the intention to combat crime and drug-related violence.[38] In October 2022, bloody riot among inmates at a prison in central Ecuador caused 16 deaths, among them was the drug lord Leonardo Norero, alias "El Patron." In Ecuador's state prisons there been numerous bloody clashes between rival groups of prisoners.[39]

Lasso proposed a series of constitutional changes to enhance his government's ability to respond to rising, largely drug-related crime. In a referendum in February 2023, voters overwhelmingly rejected his proposed changes. This result weakened Lasso's political standing.[40]

^ Ferdon, Edwin N. (24 June 1966). "The Prehistoric Culture of Ecuador: Early Formative Period of Coastal Ecuador: The Valdivia and Machalilla Phases . Betty J. Meggers, Clifford Evans, and Emilio Estrada. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1965. 452 pp., $6.75". Science. 152 (3730): 1731–1732. doi:10.1126/science.152.3730.1731. ISSN 0036-8075. ^ "Valdivia Figurines". Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. Retrieved 29 June 2022. ^ Meggers, Betty J.; Evans, Clifford; Estrada, Emilio (1965). "Early Formative Period of Coastal Ecuador: The Valdivia and Machalilla Phases". Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology: 1–234. doi:10.5479/si.00810223.1.1. hdl:10088/19154. Retrieved 29 June 2022. ^ "Quito History - Culture, Religion and Lifestyle in Quito". www.quito.com. Retrieved 25 July 2022. ^ Sandoval, José R.; Lacerda, Daniela R.; Jota, Marilza M. S.; Robles-Ruiz, Paulo; Danos, Pierina; Paz-y-Miño, César; Wells, Spencer; Santos, Fabrício R.; Fujita, Ricardo (10 September 2020). "Tracing the genetic history of the 'Cañaris' from Ecuador and Peru using uniparental DNA markers". BMC Genomics. 21 (Suppl 7): 413. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-06834-1. PMC 7488242. PMID 32912150. ^ Lavilla, E.O. (2004). "Under the Southern Cross: Stories around Humboldt and Bonpland's trip to the New Continent" (PDF). Latin American Applied Research. 34: 203–208. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010. ^ "Ecuador en el día de la Independencia nacional". El Telégrafo (in European Spanish). 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018. ^ "Galápagos celebra un año más de provincialización" (in Spanish). Presidencia de la República del Ecuador. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2021. ^ "Assessment for Blacks in Ecuador". CIDCM. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. ^ Zook, David H. (1964). Zarumilla-Marañón: the Ecuador-Peru dispute (First ed.). New York: New York, Bookman Associates. pp. 15–36. ^ Roos, Wilma and van Renterghem, Omer Ecuador, New York, 2000, p.5. ^ a b "Uppsala Conflict Data Program – Conflict Encyclopedia, General Conflict Information, Conflict name: Ecuador – Peru, In depth, Background to the 1995 fighting and Ecuador and Peru engage in armed conflict". Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013. ^ Apology Of An Economic Hitman (2010), retrieved 21 September 2021 ^ "Outsourcing the Money Supply". ^ "Ecuador's one and only official currency is the US Dollar". People Places and Thoughts. ^ "Ecuador Congress ousts president". www.aljazeera.com. ^ Forero, Juan (22 April 2005). "Ecuador's New Chief Picks Cabinet; Leftist in Economic Post". The New York Times. ^ "Leftist rolling to victory in Ecuador's presidential race". Los Angeles Times. 27 November 2006. ^ "Ecuador's new president sworn in". www.aljazeera.com. ^ "Ecuador referendum endorses new socialist constitution". The Guardian. 29 September 2008. ^ "Avenger against oligarchy" wins in Ecuador The Real News, 27 April 2009. ^ Romero, Simon (April 27, 2009). "Ecuador Re-elects President, Preliminary Results Show". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017. ^ "Most Popular E-mail Newsletter". USA Today. May 7, 2011. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2017. ^ "Public spending fuels Ecuador leader's popularity". Voxxi.com. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2012. ^ "Correa's and Ecuador's Success drive The Economist Nuts" Archived 16 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. New Economic Perspectives. ^ Correa wins re-election and says banks and mass media don't rule anymore Archived 18 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Real News. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014. "Unemployment hit a record low of 4.1 percent at the end of last year. Poverty's down about 27 percent since he took office". – Mark Weisbrot, co-director of Center for Economic and Policy Research ^ In August 2018, Ecuador withdrew from Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (Alba), a regional bloc of leftwing governments led by Venezuela. ^ "Équateur : Lenín Moreno et le néolibéralisme par surprise – Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières". www.europe-solidaire.org. ^ "Ecuador, Venezuela sever diplomatic ties due to improper accusations". ^ "Trump Receives Ecuadorian President Lenín Moreno". 13 February 2020. ^ "Outcry as Ecuador allows US military to use Galapagos airstrip". 18 June 2019. ^ "Protesters move into Ecuador's capital; president moves out". ABC News. Retrieved 10 October 2019. ^ Kueffner, tephan (10 October 2019). "Ecuador Government Returns to Capital Amid National Strike". Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 October 2019. ^ "Ecuador repeals law ending fuel subsidies in deal to stop protests". BBC News. 14 October 2019. ^ "Guillermo Lasso: Conservative ex-banker elected Ecuador president". BBC News. 12 April 2021. ^ "Lasso inaugurated as first right-wing Ecuador president in 14 years". France24. Agence France Presse. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021. ^ García, Alberto (16 April 2021). "Lenín Moreno's legacy to Guillermo Lasso in Ecuador". Atalayar.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021. ^ "Ecuador president declares state of emergency over drug violence". www.aljazeera.com. ^ "Drug capo among 16 dead in bloody Ecuador prison riot". Washington Post. ^ ""El partido del presidente Lasso ha tenido un desempeño muy deficiente", dice analista". CNN Español. Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- Stay safe

Mountaineering is a popular activity here, though it can be dangerous in many ways

Mountaineering is a popular activity here, though it can be dangerous in many waysTourists should use common sense to ensure their safety. Avoid problems by not flashing large amounts of money, not visiting areas near the Colombian border, staying away from civil disturbances and not using side streets in big cities at night. Probably the biggest threat in most places is simple thievery: belongings should not be left unguarded on the beach, for example, and pickpockets can be found in some of the more crowded areas, especially the Trolébus (Metro) in Quito, in bus terminals and on the buses themselves. Buses allow peddlers to board briefly and attempt to sell their wares; however, they are often thieves themselves, so keep a close eye out for them. Hotel personnel are generally good sources of information about places that should be avoided.

You can always ask tourist police officers, police officers or in tourist information center for the dangerous regions.

Ecuador offers great opportunities for hiking and climbing; unfortunately, some travelers have been attacked and robbed in remote sections of well known climbs and several rapes have also been reported, so female hikers and climbers need to be extremely careful. Travelers are urged to avoid solo hikes and to go in a large group for safety reasons.