México

MexicoContext of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and to the east by the Gulf of Mexico. Mexico covers 1,972,550 km2 (761,610 sq mi), making it the world's 13th-largest country by area; with a population of over 126 million, it is the 10th-most-populous country and has the most Spanish speakers. Mexico is organized as a federal republic comprising 31 states and Mexico City, its capital. Other major urban areas include Monterrey, Guadalajara, Puebla, Toluca, Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and León.

Human presence in Pre-Columbian Mexico goes back to 8,000 BCE and it went to become one of the world's six cradles of civilization. In particular, the Mesoamerican region was home to many intertwined civili...Read more

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and to the east by the Gulf of Mexico. Mexico covers 1,972,550 km2 (761,610 sq mi), making it the world's 13th-largest country by area; with a population of over 126 million, it is the 10th-most-populous country and has the most Spanish speakers. Mexico is organized as a federal republic comprising 31 states and Mexico City, its capital. Other major urban areas include Monterrey, Guadalajara, Puebla, Toluca, Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and León.

Human presence in Pre-Columbian Mexico goes back to 8,000 BCE and it went to become one of the world's six cradles of civilization. In particular, the Mesoamerican region was home to many intertwined civilizations, including the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, and Purepecha. Last were the Aztecs, who dominated the region in the century before European contact. In 1521, the Spanish Empire and its indigenous allies conquered the Aztec Empire from its capital Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City), establishing the colony of New Spain.

Over the next three centuries, Spain and the Catholic Church played an important role, expanding the territory, enforcing Christianity and spreading the Spanish language throughout. With the discovery of rich deposits of silver in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, New Spain soon became one of the most important mining centers worldwide. Wealth coming from Asia and the New World contributed to Spain's status as a major world power for the next centuries, and brought about a price revolution in Western Europe. The colonial order came to an end in the early nineteenth century with the War of Independence against Spain.

Mexico's early history as an independent nation state was marked by political and socioeconomic upheaval, both domestically and in foreign affairs. The Federal Republic of Central America shortly seceded the country. Then two invasions by foreign powers took place: first, by the United States as a consequence of the Texas Revolt by American settlers, which led to the Mexican–American War and huge territorial losses in 1848. After the introduction of liberal reforms in the Constitution of 1857, conservatives reacted with the war of Reform and prompted France to invade the country and install an Empire, against the Republican resistance led by liberal President Benito Juárez, which emerged victorious. The last decades of the 19th century were dominated by the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, who sought to modernize Mexico and restore order. However, the Porfiriato era led to great social unrest and ended with the outbreak in 1910 of the decade-long Mexican Revolution (civil war). This conflict led to profound changes in Mexican society, including the proclamation of the 1917 Constitution, which remains in effect to this day. The remaining war generals ruled as a succession of presidents until the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) emerged in 1929.

The PRI governed Mexico for the next 70 years, first under a set of paternalistic developmental policies of considerable economic success. During World War II Mexico also played an important role for the Allied war effort. Nonetheless, the PRI regime resorted to repression and electoral fraud to maintain power, and moved the country to a more US-aligned neoliberal economic policy during the late 20th century. This culminated with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, which caused a major indigenous rebellion in the state of Chiapas. PRI lost the presidency for the first time in 2000, against the conservative party (PAN).

Mexico has the world's 15th-largest economy by nominal GDP and the 11th-largest by PPP, with the United States being its largest economic partner. As a newly industrialized and developing country ranking 86th, high in the Human Development Index, its large economy and population, cultural influence, and steady democratization make Mexico a regional and middle power which is also identified as an emerging power by several analysts. Mexico ranks first in the Americas and seventh in the world for the number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It is also one of the world's 17 megadiverse countries, ranking fifth in natural biodiversity. Mexico's rich cultural and biological heritage, as well as varied climate and geography, makes it a major tourist destination: as of 2018, it was the sixth most-visited country in the world, with 39 million international arrivals. However, the country continues to struggle with social inequality, poverty and extensive crime. It ranks poorly on the Global Peace Index, due in large part to ongoing conflict between drug trafficking syndicates, which violently compete for the US drug market and trade routes. This "drug war" has led to over 120,000 deaths since 2006. Mexico is a member of United Nations, the G20, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, the Organization of American States, Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, and the Organization of Ibero-American States.

More about Mexico

- Currency Mexican peso

- Native name México

- Calling code +52

- Internet domain .mx

- Mains voltage 127V/60Hz

- Democracy index 6.07

- Population 131135337

- Area 1972550

- Driving side right

- Indigenous civilizations before European contact (pre-1519)

Read moreIndigenous civilizations before European contact (pre-1519)Read less

Read moreIndigenous civilizations before European contact (pre-1519)Read less Teotihuacan, the 6th largest city in the world at its peak (1 AD to 500 AD)

Teotihuacan, the 6th largest city in the world at its peak (1 AD to 500 AD) Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo) in the Maya city of Chichen Itza

Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo) in the Maya city of Chichen Itza Artistic depiction of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital and largest city in the Americas at the time. The city was completely destroyed in the 1521 siege of Tenochtitlan and rebuilt as Mexico City.

Artistic depiction of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital and largest city in the Americas at the time. The city was completely destroyed in the 1521 siege of Tenochtitlan and rebuilt as Mexico City.The prehistory of Mexico stretches back millennia. The earliest human artifacts in Mexico are chips of stone tools found near campfire remains in the Valley of Mexico and radiocarbon-dated to circa 10,000 years ago.[1] Mexico is the site of the domestication of maize, tomato, and beans, which produced an agricultural surplus. This enabled the transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers to sedentary agricultural villages beginning around 5000 BCE.[2] In the subsequent formative eras, maize cultivation and cultural traits such as a mythological and religious complex, and a vigesimal (base 20) numeric system, were diffused from the Mexican cultures to the rest of the Mesoamerican culture area.[3] In this period, villages became more dense in terms of population, becoming socially stratified with an artisan class, and developing into chiefdoms. The most powerful rulers had religious and political power, organizing the construction of large ceremonial centers.[4]

The earliest complex civilization in Mexico was the Olmec culture, which flourished on the Gulf Coast from around 1500 BCE. Olmec cultural traits diffused through Mexico into other formative-era cultures in Chiapas, Oaxaca and the Valley of Mexico. The formative period saw the spread of distinct religious and symbolic traditions, as well as artistic and architectural complexes.[5] The formative-era of Mesoamerica is considered one of the six independent cradles of civilization. In the subsequent pre-classical period, the Maya and Zapotec civilizations developed complex centers at Calakmul and Monte Albán, respectively. During this period the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and the Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya Hieroglyphic script. The earliest written histories date from this era. The tradition of writing was important after the Spanish conquest in 1521, with indigenous scribes learning to write their languages in alphabetic letters, while also continuing to create pictorial texts.[6][7]

In Central Mexico, the height of the classic period saw the ascendancy of Teotihuacán, which formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area as well as north. Teotihuacan, with a population of more than 150,000 people, had some of the largest pyramidal structures in the pre-Columbian Americas.[8] After the collapse of Teotihuacán around 600 AD, competition ensued between several important political centers in central Mexico such as Xochicalco and Cholula. At this time, during the Epi-Classic, Nahua peoples began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mexico, as they displaced speakers of Oto-Manguean languages. During the early post-classic era (ca. 1000–1519 CE), Central Mexico was dominated by the Toltec culture, Oaxaca by the Mixtec, and the lowland Maya area had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Toward the end of the post-Classic period, the Mexica established dominance, establishing a political and economic empire based in the city of Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico City), extending from central Mexico to the border with Guatemala.[9] Alexander von Humboldt popularized the modern usage of "Aztec" as a collective term applied to all the people linked by trade, custom, religion, and language to the Mexica state and Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, the Triple Alliance.[10] In 1843, with the publication of the work of William H. Prescott, it was adopted by most of the world, including 19th-century Mexican scholars who considered it a way to distinguish present-day Mexicans from pre-conquest Mexicans. This usage has been the subject of debate since the late 20th century.[11]

The Aztec empire was an informal or hegemonic empire because it did not exert supreme authority over the conquered territories; it was satisfied with the payment of tributes from them. It was a discontinuous empire because not all dominated territories were connected; for example, the southern peripheral zones of Xoconochco were not in direct contact with the center. The hegemonic nature of the Aztec empire was demonstrated by their restoration of local rulers to their former position after their city-state was conquered. The Aztec did not interfere in local affairs, as long as the tributes were paid.[12] The Aztec of Central Mexico built a tributary empire covering most of central Mexico.[13] The Aztec were noted for practicing human sacrifice on a large scale. Along with this practice, they avoided killing enemies on the battlefield. Their warring casualty rate was far lower than that of their Spanish counterparts, whose principal objective was immediate slaughter during battle.[14] This distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition of human sacrifice ended with the gradually Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Other Mexican indigenous cultures were conquered and gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule.[15]

Since the colonial era and through to the twenty-first century, the indigenous roots of Mexican history and culture are essential to Mexican identity. The National Museum of Anthrology in Mexico City is the showcase of the nation's prehispanic glories. Historian Enrique Florescano calls it "a national treasure and a symbol of identity. The museum is the synthesis of an ideological, scientific, and political feat."[16] Mexican Nobel laureate Octavio Paz said of the museum that the "exaltation and glorification of Mexico-Tenochtitlan transforms the Museum of Anthropology into a temple."[17] Mexico pursued international recognition of its prehispanic heritage, and has a large number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the largest in the hemisphere. The existence of high indigenous civilization prior to the arrival of Europeans has also had an impact on European thought.[18]

Spanish conquest and colonial era (1519–1821) Storming of the Teocalli by Cortez and his Troops (1848)

Storming of the Teocalli by Cortez and his Troops (1848)Although the Spanish Empire had established colonies in the Caribbean starting in 1493, only in the second decade of the sixteenth century did they begin exploring the east coast of Mexico. The Spanish first learned of Mexico during the Juan de Grijalva expedition of 1518. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire began in February 1519 when Hernán Cortés landed on the Gulf Coast and founded the Spanish city of Veracruz. Around 500 conquistadores, along with horses, cannons, swords, and long guns gave the Spanish some technological advantages over indigenous warriors, but key to the Spanish victory was making strategic alliances with disgruntled indigenous city-states (altepetl) who fought with them against the Aztec Triple Alliance. Also important to the Spanish victory was Cortés's cultural translator, Malinche, a Nahua woman enslaved in the Maya area whom the Spanish acquired as a gift. She quickly learned Spanish and gave strategic advice about how to deal with both indigenous allies and indigenous foes.[19]

The Spanish conquest is well documented from multiple points of view. There are accounts by the Spanish leader Cortés[20] and multiple other Spanish participants, including Bernal Díaz del Castillo.[21][22] There are indigenous accounts in Spanish, Nahuatl, and pictorial narratives by allies of the Spanish, most prominently the Tlaxcalans, as well as Texcocans[23] and Huejotzincans, and the defeated Mexica themselves, recorded in the last volume of Bernardino de Sahagún's General History of the Things of New Spain.[24][25][26]

View of the Plaza Mayor (today Zócalo) in Mexico City (ca. 1695) by Cristóbal de Villalpando

View of the Plaza Mayor (today Zócalo) in Mexico City (ca. 1695) by Cristóbal de VillalpandoThe 1521 capture of Tenochtitlan and immediate founding of the Spanish capital Mexico City on its ruins was the beginning of a 300-year-long colonial era during which Mexico was known as Nueva España (New Spain). Two factors made Mexico a jewel in the Spanish Empire: the existence of large, hierarchically organized Mesoamerican populations that rendered tribute and performed obligatory labor and the discovery of vast silver deposits in northern Mexico.[27] The Kingdom of New Spain was created from the remnants of the Aztec empire. The two pillars of Spanish rule were the State and the Roman Catholic Church, both under the authority of the Spanish crown. In 1493 the pope had granted sweeping powers to the Spanish monarchy for its overseas empire, with the proviso that the crown spread Christianity in its new realms. In 1524, King Charles I created the Council of the Indies based in Spain to oversee State power its overseas territories; in New Spain the crown established a high court in Mexico City, the Real Audiencia, and then in 1535 created the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The viceroy was highest official of the State. In the religious sphere, the diocese of Mexico was created in 1530 and elevated to the Archdiocese of Mexico in 1546, with the archbishop as the head of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, overseeing Roman Catholic clergy. Castilian Spanish was the language of rulers. The Catholic faith the only one permitted, with non-Catholics (Jews and Protestants) and Catholics (excluding Indians) holding unorthodox views being subject to the Mexican Inquisition, established in 1571.[28]

In the first half-century of Spanish rule, a network of Spanish cities was created, sometimes on pre-Columbian sites where there were dense indigenous populations. The capital Mexico City was and remains the premier city, but other cities founded in the sixteenth century remain important, including Puebla, Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Zacatecas, Oaxaca, and the port of Veracruz. Cities and towns were hubs of civil officials, ecclesiastics, business, Spanish elites, and mixed-race and indigenous artisans and workers. When deposits of silver were discovered in sparsely populated northern Mexico, far from the dense populations of central Mexico, the Spanish secured the region against fiercely resistant indigenous Chichimecas. The Viceroyalty at its greatest extent included the territories of modern Mexico, Central America as far south as Costa Rica, and the western United States. The Viceregal capital Mexico City also administrated the Spanish West Indies (the Caribbean), the Spanish East Indies (that is, the Philippines), and Spanish Florida. In 1819, the Spain signed the Adams-Onís Treaty with the United States, setting New Spain's northern boundary.[29]

New Spain was essential to the Spanish global trading system. White represents the route of the Spanish Manila Galleons in the Pacific and the Spanish convoys in the Atlantic (blue represents Portuguese routes).

New Spain was essential to the Spanish global trading system. White represents the route of the Spanish Manila Galleons in the Pacific and the Spanish convoys in the Atlantic (blue represents Portuguese routes).The rich deposits of silver, particularly in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, resulted in silver extraction dominating the economy of New Spain. Mexican silver pesos became the first globally used currency. Taxes on silver production became a major source of income for the Spanish monarchy. Other important industries were the agricultural and ranching haciendas and mercantile activities in the main cities and ports.[citation needed] As a result of its trade links with Asia, the rest of the Americas, Africa and Europe and the profound effect of New World silver, central Mexico was one of the first regions to be incorporated into a globalized economy. Being at the crossroads of trade, people and cultures, Mexico City has been called the "first world city".[30] The Nao de China (Manila Galleons) operated for two and a half centuries and connected New Spain with Asia. Silver and the red dye cochineal were shipped from Veracruz to Atlantic ports in the Americas and Spain. Veracruz was also the main port of entry in mainland New Spain for European goods, immigrants from Spain, and African slaves. The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro connected Mexico City with the interior of New Spain.

The population of Mexico was overwhelmingly indigenous and rural during the entire colonial period and beyond, despite the massive decrease in their numbers due to epidemic diseases. Diseases such as smallpox, measles, and others were introduced by Europeans and African slaves, especially in the sixteenth century. The indigenous population stabilized around one to one and a half million individuals in the 17th century from the most commonly accepted five to thirty million pre-contact population.[31] During the three hundred years of the colonial era, Mexico received between 400,000 and 500,000 Europeans,[32] between 200,000 and 250,000 African slaves.[33] and between 40,000 and 120,000 Asians.[34][35]

Under Viceroy Revillagigedo the first comprehensive census was created in 1793, with racial classifications. Although most of its original datasets have reportedly been lost, thus most of what is known about it comes from essays and field investigations made by scholars who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works such as German scientist Alexander von Humboldt. Europeans ranged from 18% to 22% of New Spain's population, Mestizos from 21% to 25%, Indians from 51% to 61% and Africans were between 6,000 and 10,000. The total population ranged from 3,799,561 to 6,122,354. It is concluded that the population growth trends of whites and mestizos were even, while the percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%–17% per century, mostly due to the latter having higher mortality rates from living in remote locations and being in constant war with the colonists.[36] Independence-era Mexico eliminated the legal basis for the hierarchical system of racial classification, although the racial/ethnic labels continued to be used.

Luis de Mena, Virgin of Guadalupe and castas, showing race mixture and hierarchy as well as fruits of the realm,[37] ca. 1750

Luis de Mena, Virgin of Guadalupe and castas, showing race mixture and hierarchy as well as fruits of the realm,[37] ca. 1750Colonial law with Spanish roots was introduced and attached to native customs creating a hierarchy between local jurisdiction (the Cabildos) and the Spanish Crown. Upper administrative offices were closed to native-born people, even those of pure Spanish blood (criollos). Administration was based on the racial separation. Society was organized in a racial hierarchy, with whites on top, mixed-race persons and blacks in the middle, and indigenous at the bottom. There were formal legal designations of racial categories. The Republic of Spaniards (República de Españoles) comprised European- and American-born Spaniards, mixed-race castas, and black Africans. The Republic of Indians (República de Indios) comprised the indigenous populations, which the Spanish lumped under the term Indian (indio), a Spanish colonial social construct which indigenous groups and individuals rejected as a category. Spaniards were exempt from paying tribute, Spanish men had access to higher education, could hold civil and ecclesiastical offices, were subject to the Inquisition, and liable for military service when the standing military was established in the late eighteenth century. Indigenous paid tribute, but were exempt from the Inquisition, indigenous men were excluded from the priesthood; and exempt from military service. Although the racial system appears fixed and rigid, there was some fluidity within it, and racial domination of whites was not complete.[38] Since the indigenous population of New Spain was so large, there was less labor demand for expensive black slaves than other parts of Spanish America.[39][40] In the late eighteenth century the crown instituted reforms that privileged Iberian-born Spaniards (peninsulares) over American-born (criollos), limiting their access to offices. This discrimination between the two became a sparking point of discontent for white elites in the colony.[41]

The Marian apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe said to have appeared to the indigenous Juan Diego in 1531 gave impetus to the evangelization of central Mexico.[42][43] The Virgin of Guadalupe became a symbol for American-born Spaniards' (criollos) patriotism, seeking in her a Mexican source of pride, distinct from Spain.[44] The Virgin of Guadalupe was invoked by the insurgents for independence who followed Father Miguel Hidalgo during the War of Independence.[43]

Spanish military forces, sometimes accompanied by native allies, led expeditions to conquer territory or quell rebellions through the colonial era. Notable Amerindian revolts in sporadically populated northern New Spain include the Chichimeca War (1576–1606),[45] Tepehuán Revolt (1616–1620),[46] and the Pueblo Revolt (1680), the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712 was a regional Maya revolt.[47] Most rebellions were small-scale and local, posing no major threat to the ruling elites.[48] To protect Mexico from the attacks of English, French, and Dutch pirates and protect the Crown's monopoly of revenue, only two ports were open to foreign trade—Veracruz on the Atlantic and Acapulco on the Pacific. Among the best-known pirate attacks are the 1663 Sack of Campeche[49] and 1683 Attack on Veracruz.[50] Of greater concern to the crown was of foreign invasion, especially after Britain seized in 1762 the Spanish ports of Havana, Cuba and Manila, the Philippines in the Seven Years' War. It created a standing military, increased coastal fortifications, and expanded the northern presidios and missions into Alta California. The volatility of the urban poor in Mexico City was evident in the 1692 riot in the Zócalo. The riot over the price of maize escalated to a full-scale attack on the seats of power, with the viceregal palace and the archbishop's residence attacked by the mob.[38]

Independence era (1808–1821) Siege of the Alhondiga de Granaditas, Guanajuato, 28 September 1810

Siege of the Alhondiga de Granaditas, Guanajuato, 28 September 1810The upheaval in the Spanish Empire that resulted in the independence of most of its New World territories was due to Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Spain in 1808. Napoleon forced the abdication of the Spanish monarch Charles IV and imposed of his brother Joseph Bonaparte as the Spanish king. Now with an alien usurper on the Spanish throne, there was a crisis of legitimacy of the monarchy, resulting in various responses in both Spain and Spanish America. In Mexico, elites argued that sovereignty now reverted to "the people" and that town councils (cabildos) were the most representative bodies. American-born Spaniards petitioned the viceroy José de Iturrigaray (1803–08) to convene a junta to determine rule in Mexico in the current political crisis. Although Peninsular-born Spaniards were opposed to the plan, the viceroy called together wealthy landowners, miners, merchants, ecclesiastics, academics, and members of cabildos. They failed to come to agreement, and in the meantime, Peninsular-born Spaniards took the initiative, arresting Iturrigaray and leading creole elites in the capital. The coup ended what could have been a peaceful process toward political autonomy in Mexico. Creoles now sought extralegal means to achieve their political aspirations.[51]

On 16 September 1810, secular priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla declared against "bad government" in the small town of Dolores, Guanajuato. This event, known as the Cry of Dolores (Spanish: Grito de Dolores) is commemorated each year, on 16 September, as Mexico's independence day.[52] The first insurgent group was formed by Hidalgo, army captain Ignacio Allende, the militia captain Juan Aldama and the wife of the local magistrate (Corregidor) Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, known as La Corregidora. Hidalgo's local declaration sparked a huge revolt of the masses, an uncontrollable uprising targeting the persons and property of white elites, whether Peninsular- or American-born. Famously in Guanajuato, elites took refuge in the central grain storage (alhondiga), bringing their treasure, attempted to hold out against Hidalgo's followers, but were slaughtered. In an event emblematic of the war of independence, "Hidalgo's capture of the great silver city of Guanajuato on September 28, 1810, is the most famous single episode of the decade-long insurgency."[53] Hidalgo and some of his soldiers were eventually captured, Hidalgo was defrocked, and they were executed by firing squad in Chihuahua, on 31 July 1811. The heads of the executed rebels were subsequently displayed on the granary. Following Hidalgo's death, Ignacio López Rayón and then by the priest José María Morelos assumed the leadership, occupying key southern cities with the support of Mariano Matamoros and Nicolás Bravo. In 1813 the Congress of Chilpancingo was convened and, on 6 November, signed the "Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America". This Act also called for the abolition of slavery and the system of racial hierarchy, and Roman Catholicism the sole religion. Morelos was captured and executed on 22 December 1815.

Flag of the Army of the Three Guarantees, the force formed by ex-royalist Iturbide and insurgent Vicente Guerrero in February 1821

Flag of the Army of the Three Guarantees, the force formed by ex-royalist Iturbide and insurgent Vicente Guerrero in February 1821In subsequent years, the insurgency was a stalemate, but in 1820 when Spanish liberals seized power in Spain, and Mexican conservatives worried about the imposition of liberal principles overseas, including curtailment of the power of the Catholic Church. Royalist criollo general Agustín de Iturbide was to continue fighting against Vicente Guerrero and insurgents in the south. Instead of attacking Guerrero, Itubide approached Guerrero to join forces to seize power in Mexico. Iturbide issued the Plan of Iguala on 24 February 1821. Sometimes called the Act of Independence, it called for Roman Catholicism as the nation's sole religion; the establishment of a constitutional monarchy; and the equality of those born in Spain and those born in Mexico, the "three guarantees" can be summarized as "religion, independence, and union". All were to be equal citizens in the new sovereign nation, regardless of place of birth or racial category, a requirement that Guerrero, the mixed-race leader of the insurgency, insisted on for his joining with Iturbide. The flag of the newly formed Army of the Three Guarantees has evolved into today's Mexican flag. On 24 August 1821 in incoming Viceroy and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba and the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire", which recognized the independence of Mexico under the terms of the Plan of Iguala. The Spanish crown repudiated the 1821 treaty and did not formally recognize the independence of Mexico until 1836.

Early Post-Independence (1821–1855) Map of the First Mexican Empire

Map of the First Mexican EmpireThe first 35 years after Mexico's independence were marked by political instability and the changing of the Mexican state from a transient monarchy to a fragile federated republic.[54] There were military coups d'état, foreign invasions, ideological conflict between Conservatives and Liberals, and economic stagnation. Catholicism remained the only permitted religious faith and the Catholic Church as an institution retained its special privileges, prestige, and property, a bulwark of Conservatism. The army, another Conservative-dominated institution, also retained its privileges. Former Royal Army General Agustín de Iturbide, became regent, as newly independent Mexico sought a constitutional monarch from Europe. When no member of a European royal house desired the position, Iturbide himself was declared Emperor Agustín I. The young and weak United States was the first country to recognize Mexico's independence, sending an ambassador to the court of the emperor and sending a message to Europe via the Monroe Doctrine not to intervene in Mexico. The emperor's rule was short (1822–1823) and he was overthrown by army officers in the Plan of Casa Mata.[55]

After the forced abdication of the monarch, the First Mexican Republic was established. In 1824, a constitution of a federated republic was promulgated and former insurgent General Guadalupe Victoria became the first president of the republic, the first of many army generals to hold the presidency of Mexico. Central America, including Chiapas, left the union. In 1829, former insurgent general and fierce Liberal Vicente Guerrero, a signatory of the Plan de Iguala that achieved independence, became president in a disputed election. During his short term in office, April to December 1829, he abolished slavery. As a visibly mixed-race man of modest origins, Guerrero was seen by white political elites as an interloper.[56] His Conservative vice president, former Royalist General Anastasio Bustamante, led a coup against him and Guerrero was judicially murdered.[57] There was constant strife between the Liberals (also known as Federalists), who were supporters of a federal form of decentralized government, and their political rivals, the Conservatives (also known as Centralists), who proposed a hierarchical form of government.

General Antonio López de Santa Anna

General Antonio López de Santa AnnaMexico's ability to maintain its independence and establish a viable government was in question. Spain attempted to reconquer its former colony during the 1820s, but eventually recognized its independence. France attempted to recoup losses it claimed for its citizens during Mexico's unrest and blockaded the Gulf Coast during the so-called Pastry War of 1838–1839.[58] General Antonio López de Santa Anna emerged as a national hero because of his role in both these conflicts; he lost a leg in combat during the Pastry War, which he used for political purposes to show his sacrifice for the nation. Santa Anna came to dominate the politics for the next 25 years, often known as the "Age of Santa Anna", until his own overthrow in 1855.[59]

Mexico also contended with indigenous groups which controlled territory that Mexico claimed in the north. The Comanche controlled a huge territory in the sparsely populated region of central and northern Texas.[60] Wanting to stabilize and develop the frontier, the Mexican government encouraged Anglo-American immigration into present-day Texas, a region that bordered that United States. There were few settlers from central Mexico moving to this remote and hostile territory. Mexico by law was a Catholic country; the Anglo Americans were primarily Protestant English speakers from the southern United States. Some brought their black slaves, which after 1829 was contrary to Mexican law. In 1835, Santa Anna sought to centralize government rule in Mexico, suspending the 1824 constitution and promulgating the Seven Laws, which placed power in his hands. As a result, civil war spread across the country. Three new governments declared independence: the Republic of Texas, the Republic of the Rio Grande and the Republic of Yucatán.[61]: 129–137 The largest blow to Mexico was the U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1846 in the Mexican–American War. Mexico lost much of its sparsely populated northern territory, sealed in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Despite that disastrous loss, Conservative Santa Anna returned to the presidency yet again and then was ousted and exiled in the Liberal Revolution of Ayutla.

Liberal era (1855–1911) Portrait of Liberal President Benito Juárez

Portrait of Liberal President Benito JuárezThe overthrow of Santa Anna and the establishment of a civilian government by Liberals allowed them to enact laws that they considered vital for Mexico's economic development. It was a prelude to more civil wars and yet another foreign invasion. The Liberal Reform attempted to modernize Mexico's economy and institutions along liberal principles. They promulgated a new Constitution of 1857, separating Church and State, stripping the Conservative institutions of the Church and the military of their special privileges (fueros); mandating the sale of Church-owned property and sale of indigenous community lands, and secularizing education.[62] Conservatives revolted, touching off civil war between rival Liberal and Conservative governments (1858–61).

The Liberals defeated the Conservative army on the battlefield, but Conservatives sought another solution to gain power via foreign intervention by the French. Mexican conservatives asked Emperor Napoleon III to place a European monarch as head of state in Mexico. The French Army defeated the Mexican Army and placed Maximilian Hapsburg on the newly established throne of Mexico, supported by Mexican Conservatives and propped up by the French Army. The Liberal republic under Benito Juárez was basically a government in internal exile, but with the end of the Civil War in the U.S. in April 1865, that government began aiding the Mexican Republic. Two years later, the French Army withdrew its support, Maximilian remained in Mexico rather than return to Europe. Republican forces captured him and he was executed in Querétaro, along with two Conservative Mexican generals. The "Restored Republic" saw the return of Juárez, who was "the personification of the embattled republic,"[63] as president.

The Conservatives had been not only defeated militarily, but also discredited politically for their collaboration with the French invaders. Liberalism became synonymous with patriotism.[64] The Mexican Army that had its roots in the colonial royal army and then the army of the early republic was destroyed. New military leaders had emerged from the War of the Reform and the conflict with the French, most notably Porfirio Díaz, a hero of the Cinco de Mayo, who now sought civilian power. Juárez won re-election in 1867, but was challenged by Díaz, who criticized him for running for re-election. Díaz then rebelled, crushed by Juárez. Having won re-election, Juárez died in office of natural causes in July 1872, and Liberal Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada became president, declaring a "religion of state" for rule of law, peace, and order. When Lerdo ran for re-election, Díaz rebelled against the civilian president, issuing the Plan of Tuxtepec. Díaz had more support and waged guerrilla warfare against Lerdo. On the verge of Díaz's victory on the battlefield, Lerdo fled from office, going into exile.[65]

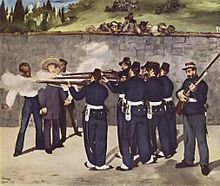

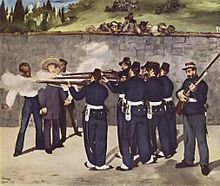

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 19 June 1867. Gen. Tomás Mejía, left, Maximiian, center, Gen. Miguel Miramón, right. Painting by Édouard Manet 1868.

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 19 June 1867. Gen. Tomás Mejía, left, Maximiian, center, Gen. Miguel Miramón, right. Painting by Édouard Manet 1868.After the turmoil in Mexico from 1810 to 1876, the 35-year rule of Liberal General Porfirio Díaz (r.1876–1911) allowed Mexico to rapidly modernize in a period characterized as one of "order and progress". The Porfiriato was characterized by economic stability and growth, significant foreign investment and influence, an expansion of the railroad network and telecommunications, and investments in the arts and sciences.[66] The period was also marked by economic inequality and political repression. Díaz knew the potential for army rebellions, and systematically downsized the expenditure for the force, rather expanding the rural police force under direct control of the president. Díaz did not provoke the Catholic Church, coming to a modus vivendi with it; but he did not remove the anticlerical articles from the 1857 Constitution. From the late nineteenth century, Protestants began to make inroads into overwhelmingly Catholic Mexico.

The government encouraged British and U.S. investment. Commercial agriculture developed in northern Mexico, with many investors from the U.S. acquiring vast ranching estates and expanding irrigated cultivation of crops. The Mexican government ordered a survey of land with the aim of selling it for development. In this period, many indigenous communities lost their lands and the men became landless wage earners on large landed enterprises (haciendas).[67] British and U.S. investors developed extractive mining of copper, lead, and other minerals, as well as petroleum on the Gulf Coast. Changes in Mexican law allowed for private enterprises to own the subsoil rights of land, rather than continuing the colonial law that gave all subsoil rights to the State. An industrial manufacturing sector also developed, particularly in textiles. At the same time, new enterprises gave rise to an industrial work force, which began organizing to gain labor rights and protections.

Díaz ruled with a group of advisors that became known as the científicos ("scientists").[68] The most influential científico was Secretary of Finance José Yves Limantour.[69] The Porfirian regime was influenced by positivism.[70] They rejected theology and idealism in favor of scientific methods being applied towards national development. An integral aspect of the liberal project was secular education. The Díaz government led a protracted conflict against the Yaqui that culminated with the forced relocation of thousands of Yaqui to Yucatán and Oaxaca. Díaz's long success did not include planning for a political transition beyond his own presidency. He made no attempt, however, to establish a family dynasty, naming no relative as his successor. As the centennial of independence approached, Díaz gave an interview where he said he was not going to run in the 1910 elections, when he would be 80. Political opposition had been suppressed and there were few avenues for a new generation of leaders. But his announcement set off a frenzy of political activity, including the unlikely candidacy of the scion of a rich landowning family, Francisco I. Madero. Madero won a surprising amount of political support when Díaz changed his mind and ran in the election, jailing Madero. The September centennial celebration of independence was the last celebration of the Porfiriato. The Mexican Revolution starting in 1910 saw a decade of civil war, the "wind that swept Mexico."[71]

Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) Francisco I. Madero, who challenged Díaz in the fraudulent 1910 election and was elected president when Díaz was forced to resign in May 1911

Francisco I. Madero, who challenged Díaz in the fraudulent 1910 election and was elected president when Díaz was forced to resign in May 1911The Mexican Revolution was a decade-long transformational conflict in Mexico, with consequences to this day.[72] It began with scattered uprisings against President Díaz after the fraudulent 1910 election, his resignation in May 1911, demobilization of rebel forces and an interim presidency of a member of the old guard, and the democratic election of a rich, civilian landowner, Francisco I. Madero in fall 1911. In February 1913, a military coup d'état overthrew Madero's government, with the support of the U.S., resulting in Madero's murder by agents of Federal Army General Victoriano Huerta. A coalition of anti-Huerta forces in the North, the Constitutional Army led by Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza, and a peasant army in the South under Emiliano Zapata defeated the Federal Army.[73]

In 1914, that army was dissolved as an institution, leaving only revolutionary forces. Following the revolutionaries' victory against Huerta, they sought to broker a peaceful political solution, but the coalition splintered, plunging Mexico again into a civil war. Constitutionalist general Pancho Villa, commander of the Division of the North, broke with Carranza and allied with Zapata. Carranza's best general Alvaro Obregón defeated Villa, his former comrade-in-arms in the Battle of Celaya in 1915, and Villa's northern forces melted away. Zapata's forces in the south reverted to guerrilla warfare. Carranza became the de facto head of Mexico, and the U.S. recognized his government.[73]

In 1916, the winners met at a constitutional convention to draft the Constitution of 1917, which was ratified in February 1917. The Constitution empowered the government to expropriate resources including land (Article 27); gave rights to labor (Article 123); and strengthened anticlerical provisions of the 1857 Constitution.[73] With amendments, it remains the governing document of Mexico. It is estimated that the war killed 900,000 of the 1910 population of 15 million.[74][75] Although often viewed as an internal conflict, the revolution had significant international elements.[76] During the Revolution, the U.S. played a significant role with the Republican administration of Taft having supported the Huerta coup against Madero, but when Democrat Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as president in March 1913, Wilson refused to recognize Huerta's regime and allowed arms sales to the Constitutionalists. Wilson ordered troops to occupy the strategic port of Veracruz in 1914, which was lifted.[77]

Revolutionary Generals Pancho Villa (left) and Emiliano Zapata (right)

Revolutionary Generals Pancho Villa (left) and Emiliano Zapata (right)After Pancho Villa was defeated by revolutionary forces in 1915, he led an incursion raid into Columbus, New Mexico, prompting the U.S. to send 10,000 troops led by General John J. Pershing in an unsuccessful attempt to capture Villa. Carranza pushed back against U.S. troops being in northern Mexico. The expeditionary forces withdrew as the U.S. entered World War I.[78] Germany attempted to get Mexico to side with it, sending a coded telegram in 1917 to incite war between the U.S. and Mexico, with Mexico to regain the territory it lost in the Mexican-American War.[79] Mexico remained neutral in the conflict.

Consolidating power, President Carranza had peasant-leader Emiliano Zapata assassinated in 1919. Carranza had gained support of the peasantry during the Revolution, but once in power he did little to institute land reform, which had motivated many to fight in the Revolution. Carranza in fact returned some confiscated land to their original owners. President Carranza's best general, Obregón, served briefly in his administration, but returned to his home state of Sonora to position himself to run in the 1920 presidential election. Since Carranza could not run for re-election, he chose a civilian, political and revolutionary no-body to succeed him, intending to remain the power behind the presidency. Obregón and two other Sonoran revolutionary generals drew up the Plan of Agua Prieta, overthrowing Carranza, who died fleeing Mexico City in 1920. General Adolfo de la Huerta became interim president, followed the election of General Álvaro Obregón.

Political consolidation and one-party rule (1920–2000) Logo of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, that was founded in 1929 and held uninterrupted power in the country for 71 years, from 1929 to 2000

Logo of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, that was founded in 1929 and held uninterrupted power in the country for 71 years, from 1929 to 2000The first quarter-century of the post-revolutionary period (1920–1946) was characterized by revolutionary generals serving as Presidents of Mexico, including Álvaro Obregón (1920–24), Plutarco Elías Calles (1924–28), Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40), and Manuel Avila Camacho (1940–46). Since 1946, no member of the military has been President of Mexico. The post-revolutionary project of the Mexican government sought to bring order to the country, end military intervention in politics, and create organizations of interest groups. Workers, peasants, urban office workers, and even the army for a short period were incorporated as sectors of the single party that dominated Mexican politics from its founding in 1929. Obregón instigated land reform and strengthened the power of organized labor. He gained recognition from the United States and took steps to settle claims with companies and individuals that lost property during the Revolution. He imposed his fellow former Sonoran revolutionary general, Calles, as his successor, prompting an unsuccessful military revolt. As president, Calles provoked a major conflict with the Catholic Church and Catholic guerrilla armies when he strictly enforced anticlerical articles of the 1917 Constitution. The Church-State conflict was mediated and ended with the aid of the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico and ended with an agreement between the parties in conflict, by means of which the respective fields of action were defined. Although the constitution prohibited reelection of the president, Obregón wished to run again and the constitution was amended to allow non-consecutive re-election. Obregón won the 1928 elections, but was assassinated by a Catholic zealot, causing a political crisis of succession. Calles could not become president again, since he has just ended his term. He sought to set up a structure to manage presidential succession, founding the party that was to dominate Mexico until the late twentieth century. Calles declared that the Revolution had moved from caudillismo (rule by strongmen) to the era institucional (institutional era).[80]

Despite not holding the presidency, Calles remained the key political figure during the period known as the Maximato (1929–1934). The Maximato ended during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas, who expelled Calles from the country and implemented many economic and social reforms. This included the Mexican oil expropriation in March 1938, which nationalized the U.S. and Anglo-Dutch oil company known as the Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company. This movement would result in the creation of the state-owned Mexican oil company Pemex. This sparked a diplomatic crisis with the countries whose citizens had lost businesses by Cárdenas's radical measure, but since then the company has played an important role in the economic development of Mexico. Cárdenas's successor, Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940–1946) was more moderate, and relations between the U.S. and Mexico vastly improved during World War II, when Mexico was a significant ally, providing manpower and materiel to aid the war effort. From 1946 the election of Miguel Alemán, the first civilian president in the post-revolutionary period, Mexico embarked on an aggressive program of economic development, known as the Mexican miracle, which was characterized by industrialization, urbanization, and the increase of inequality in Mexico between urban and rural areas.[81]

Students in a burned bus during the protests of 1968With robust economic growth, Mexico sought to showcase it to the world by hosting the 1968 Summer Olympics. The government poured huge resources into building new facilities. At the same time, there was political unrest by university students and others with those expenditures, while their own circumstances were difficult. Demonstrations in central Mexico City went on for weeks before the planned opening of the games, with the government of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz cracking down. The culmination was the Tlatelolco Massacre,[82] which claimed the lives of around 300 protesters based on conservative estimates and perhaps as many as 800.[83] Although the economy continued to flourish for some, social inequality remained a factor of discontent. PRI rule became increasingly authoritarian and at times oppressive in what is now referred to as the Mexican Dirty War.[84]

Luis Echeverría, Minister of the Interior under Díaz Ordaz, carrying out the repression during the Olympics, was elected president in 1970. His government had to contend with mistrust of Mexicans and increasing economic problems. He instituted some with electoral reforms.[85][86] Echeverría chose José López Portillo as his successor in 1976. Economic problems worsened in his early term, then massive reserves of petroleum were located off Mexico's Gulf Coast. Pemex did not have the capacity to develop these reserves itself, and brought in foreign firms. Oil prices had been high because of OPEC's lock on oil production, and López Portilla borrowed money from foreign banks for current spending to fund social programs. Those foreign banks were happy to lend to Mexico because the oil reserves were enormous and future revenues were collateral for loans denominated in U.S. dollars. When the price of oil dropped, Mexico's economy collapsed in the 1982 Crisis. Interest rates soared, the peso devalued, and unable to pay loans, the government defaulted on its debt. President Miguel de la Madrid (1982–88) resorted to currency devaluations which in turn sparked inflation.

NAFTA signing ceremony, October 1992. From left to right: (standing) President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (Mexico), President George H. W. Bush (U.S.), and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney (Canada).

NAFTA signing ceremony, October 1992. From left to right: (standing) President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (Mexico), President George H. W. Bush (U.S.), and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney (Canada).In the 1980s the first cracks emerged in the PRI's complete political dominance. In Baja California, the PAN candidate was elected as governor. When De la Madrid chose Carlos Salinas de Gortari as the candidate for the PRI, and therefore a foregone presidential victor, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, son of former President Lázaro Cárdenas, broke with the PRI and challenged Salinas in the 1988 elections. In 1988 there was massive electoral fraud, with results showing that Salinas had won the election by the narrowest percentage ever. There were massive protests in Mexico City to the stolen election. Salinas took the oath of office on 1 December 1988.[87] In 1990 the PRI was famously described by Mario Vargas Llosa as the "perfect dictatorship", but by then there had been major challenges to the PRI's hegemony.[88][89][90]

Salinas embarked on a program of neoliberal reforms that fixed the exchange rate of the peso, controlled inflation, opened Mexico to foreign investment, and began talks with the U.S. and Canada to join their free-trade agreement. In order to do that, the Constitution of 1917 was amended in several important ways. Article 27, which had allowed the government to expropriate natural resources and distribute land, was amended to end agrarian reform and to guarantee private owners' property rights. The anti-clerical articles that muzzled religious institutions, especially the Catholic Church, were amended and Mexico reestablished of diplomatic relations with the Holy See. Signing on to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) removed Mexico's autonomy over trade policy. The agreement came into effect on 1 January 1994; the same day, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in Chiapas began armed peasant rebellion against the federal government, which captured a few towns, but brought world attention to the situation in Mexico. The armed conflict was short-lived and has continued as a non-violent opposition movement against neoliberalism and globalization. In 1994, following the assassination of the PRI's presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio, Salinas was succeeded by a victorious substitute PRI candidate Ernesto Zedillo. Salinas left Zedillo's government to deal with the Mexican peso crisis, requiring a $50 billion IMF bailout. Major macroeconomic reforms were started by President Zedillo, and the economy rapidly recovered and growth peaked at almost 7% by the end of 1999.[91]

Contemporary Mexico Vicente Fox and his opposition National Action Party won the 2000 general election, ending one-party rule.

Vicente Fox and his opposition National Action Party won the 2000 general election, ending one-party rule.In 2000, after 71 years, the PRI lost a presidential election to Vicente Fox of the opposition conservative National Action Party (PAN). In the 2006 presidential election, Felipe Calderón from the PAN was declared the winner, with a very narrow margin (0.58%) over leftist politician Andrés Manuel López Obrador then the candidate of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).[92] López Obrador, however, contested the election and pledged to create an "alternative government".[93]

After twelve years, in 2012, the PRI won the presidency again with the election of Enrique Peña Nieto, the governor of the State of Mexico from 2005 to 2011. However, he won with a plurality of about 38%, and did not have a legislative majority.[94]

After founding the new political party MORENA, Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the 2018 presidential election with over 50% of the vote. His political coalition, led by his left-wing party founded after the 2012 elections, includes parties and politicians from all over the political spectrum. The coalition also won a majority in both the upper and lower congress chambers. AMLO's (one of his many nicknames) success is attributed to the country's other strong political alternatives exhausting their chances as well as the politician adopting a moderate discourse with a focus on conciliation.[95]

Mexico has contended with high crime rates, official corruption, narcotrafficking, and a stagnant economy. Many state-owned industrial enterprises were privatized starting in the 1990s, with neoliberal reforms, but Pemex, the state-owned petroleum company is only slowly being privatized, with exploration licenses being issued.[96] In AMLO's push against government corruption, the ex-CEO of Pemex has been arrested.[97]

Although there were fears of electoral fraud in Mexico's 2018 presidential elections,[98] the results gave a mandate to AMLO.[99] On 1 December 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador was sworn in as the new President of Mexico. After winning a landslide victory in the July 2018 presidential elections, he became the first leftwing president for decades.[100] In June 2021 midterm elections, López Obrador's left-leaning Morena's coalition lost seats in the lower house of Congress. However, his ruling coalition maintained a simple majority, but López Obrador failed to secure the two-thirds congressional supermajority. The main opposition was a coalition of Mexico's three traditional parties: the center-right Revolutionary Institutional Party, right-wing National Action Party and leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution.[101]

^ Werner 2001, pp. 386–. ^ Susan Toby Evans; David L. Webster (2013). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-136-80186-0. ^ Colin M. MacLachlan (13 April 2015). Imperialism and the Origins of Mexican Culture. Harvard University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-674-28643-6. ^ Carmack, Robert M.; Gasco, Janine L.; Gossen, Gary H. (2016). The Legacy of Mesoamerica: History and Culture of a Native American Civilization. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34678-4.[page needed] ^ Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Thames & Hudson. pp. 9–25. ISBN 978-0-500-02119-4. ^ Restall, Matthew, "A History of the New Philology and the New Philology in History", Latin American Research Review - Volume 38, Number 1, 2003, pp.113–134 ^ Sampson, Geoffrey (1985). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1756-4.[page needed] ^ Cowgill, George L. (21 October 1997). "State and Society at Teotihuacan, Mexico". Annual Review of Anthropology. 26 (1): 129–161. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129. OCLC 202300854. S2CID 53663189. ^ "Ancient Civilizations of Mexico". Ancient Civilizations World. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2019. ^ "The word "Azteca" was NOT created by Von Humboldt!". Mexicka.org. 31 May 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2019. ^ León Portilla, Miguel (10 May 2009). "Los aztecas, disquisiciones sobre un gentilico". Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl. 31 (31). ^ Berdan, et al. (1996), Aztec Imperial Strategies. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC[page needed] ^ Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (2002). Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (5th edition, revised and enlarged ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28346-2. OCLC 50131575. ^ "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice". Natural History. Retrieved 16 December 2011. ^ Weaver, Muriel Porter (1993). The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-739065-9. OCLC 25832740. ^ Florescano, Enrique. "The creation of the Museo Nacional de Antropología and its scientific, educational, and political purposes." In Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science, Vol. IV p. 1257. John Hutchinson and Anthony D. Smith, eds. London and New York: Routledge 2000. ^ Octavio Paz, Posdata, Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno 1969, quoted in Florescano, "The creation of the Museo Nacional de Antropología", p. 1258, footnote 9. ^ Keen, Benjamin. The Aztec Image in Western Thought. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press 1971. ISBN 9780813515724 ^ Townsend, Camilla (2006). Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3406-0.[page needed] ^ Cortés, Hernán. Five Letters to the Emperor. Trans. J. Bayard Morris. New York: W.W. Norton 1969 ^ Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. True History of the Conquest of Mexico. various editions. Abridge version translated by J.M. Cohen, The Conquest of New Spain. London: Penguin Books 1963. ^ Fuentes, Patricia de. The Conquistadors: First-Person ccounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Norman: Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1993. ^ Alva Ixtlilxochitl, Fernando de. Ally of Cortés: Account 13 of the Coming of the Spaniards and the Beginning of Evangelical Law. Trans. Douglass K. Ballentine. El Paso: Texas Western Press 1969. ^ Altman, Ida; Cline, S. L.; Pescador, Juan Javier (2003). "Narratives of the Conquest". The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall. pp. 73–96. ISBN 978-0-13-091543-6. ^ León-Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon Press 1992. ^ Lockhart, James. We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press 1993. ^ Lockhart, James and Stuart B. Schwartz. Early Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983, 59 ^ Chuchiak, John F. IV, "Inquisition" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 704–708 ^ Salvucci, Linda. "Adams-Onís Treaty (1819)". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, pp. 11–12. ^ Sempa, Francis P. "China, Spanish America, and the 'Birth of Globalization'". The Diplomat. Retrieved 7 February 2017. Mexico City, the authors [Peter Gordon, Juan Jose Morales] note, was the 'first world city,' the precursor to London, New York, and Hong Kong, where 'Asia, Europe, and the Americas all met, and where people intermingled and exchanged everything from genes to textiles'. ^ McCaa, Robert (8 December 1997). "The Peopling of Mexico from Origins to Revolution". University of Minnesota.edu. Retrieved 13 July 2019. ^ Sluyter, Andrew (2012). Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500–1900. Yale University Press. p. 240. ISBN 9780300179927. Retrieved 8 October 2016. ^ Russell, James W. (2009). Class and Race Formation in North America. University of Toronto Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780802096784. Retrieved 13 December 2016. ^ Carrillo, Rubén. "Asia llega a América. Migración e influencia cultural asiática en Nueva España (1565–1815)". www.raco.cat. Asiadémica. Retrieved 13 December 2016. ^ The Penguin Atlas of World Population History, pp. 291–92. ^ Lerner, Victoria. "Consideraciones sobre la población de la Nueva España (1793–1810)" [Considerations on the population of New Spain (1793–1810)] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Colegio de México. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2020. ^ Cline, Sarah (1 August 2015). "Guadalupe and the Castas". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 31 (2): 218–247. doi:10.1525/mex.2015.31.2.218. S2CID 7995543. ^ a b Cope, R. Douglas. The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660–1720. Madison, Wis.: U of Wisconsin, 1994. ^ Vinson III, Ben (2017). Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02643-8.[page needed] ^ Sierra Silva, Pablo Miguel. Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Angeles 1531-1706. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018. ^ Deans-Smith, Susan. "Bourbon Reforms" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. p. 156 ^ "God intervened through Our Lady of Guadalupe to evangelize the Americas, explains Guadalupe expert", Catholic News Agency, 11 August 2009, retrieved 14 July 2019 ^ a b "Everything You Need To Know About La Virgen De Guadalupe", Huff Post Latino Voices, 12 December 2013, retrieved 14 July 2019 ^ Ortiz-Ramirez, Eduardo A. The Virgin of Guadalupe and Mexican Nationalism: Expressions of Criollo Patriotism in Colonial Images of the Virgin of Guadalupe. p. 6. ISBN 9780549596509. Retrieved 9 February 2017.[permanent dead link] ^ Schmal, John P. (17 July 2003). "The Indigenous People of Zacatecas". Latino LA: Comunidad. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2019. ^ Charlotte M. Gradie (2000). "The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616: Militarism, Evangelism, and Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century Nueva Vizcaya". The Americas. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. 58 (2): 302–303. doi:10.1353/tam.2001.0109. S2CID 144896113. ^ Wasserstrom, Robert (1980). "Ethnic Violence and Indigenous Protest: The Tzeltal (Maya) Rebellion of 1712". Journal of Latin American Studies. 12: 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00017533. S2CID 145718069. ^ Taylor, William B. (1 June 1979). Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages (1st ed.). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804711128. ^ White, Benjamin (31 January 2017). "Campeche, Mexico – largest pirate attack in history, now UNESCO listed". In Search of Lost Places. Retrieved 14 July 2019. ^ Knispel, Sandra (13 December 2017). "The mysterious aftermath of an infamous pirate raid". University of Rochester Newsletter. Retrieved 14 July 2019. ^ Altman, et al. The Early History of Greater Mexico, 342–43 ^ "Grito de Dolores". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 September 2018. ^ Van Young, Eric, Stormy Passage: Mexico from Colony to Republic, 1750-1850. (2022), 127. ^ Van Young, Stormy Passage, 179–226 ^ Benson, Nettie Lee. "The Plan of Casa Mata." Hispanic American Historical Review 25 (February 1945): 45–56. ^ Hale, Charles A. Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora. New Haven: Yale University Press 1968. p. 224 ^ "Ways of ending slavery". Encyclopædia Britannica. ^ Costeloe, Michael P. "Pastry War" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p. 318. ^ Van Young, Stormy Passage, "The Age of Santa Anna", 227–270 ^ Weber, David J., The Mexican Frontier, 1821–1846: The American Southwest under Mexico, University of New Mexico Press, 1982 ^ Angel Miranda Basurto (2002). La Evolucíon de Mėxico [The Evolution of Mexico] (in Spanish) (6th ed.). Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa. p. 358. ISBN 970-07-3678-4. ^ Britton, John A. "Liberalism" in Encyclopedia of Mexico739 ^ Hamnett, Brian. "Benito Juárez" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, pp. 719–20 ^ Britton, "Liberalism" p. 740. ^ Sullivan, Paul. "Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. pp. 736–38 ^ Adela M. Olvera (2 February 2018). "El Porfiriato en Mexico" [The Porfiriato in Mexico]. Inside Mexico.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 July 2019. ^ Hart, John Mason. Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War. Berkeley: University of California Press Du 2002 ^ Buchenau, Jürgen. "Científicos". Encyclopedia of Mexico, pp. 260–265 ^ Schmidt, Arthur, "José Ives Limantour" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, pp. 746–49. ^ "cientifico". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 February 2017. ^ Brenner, Anita (1 January 1984). The Wind that Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1942 (New ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292790247. ^ Benjamin, Thomas. La Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History. Austin: University of Texas Press 2000 ^ a b c Matute, Alvaro. "Mexican Revolution: May 1917 – December 1920" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, 862–864. ^ "The Mexican Revolution". Public Broadcasting Service. 20 November 1910. Retrieved 17 July 2013. ^ Robert McCaa. "Missing millions: the human cost of the Mexican Revolution". University of Minnesota Population Center. Retrieved 17 July 2013. ^ Katz, Friedrich. The Secret War in Mexico. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ^ "The Mexican Revolution and the United States in the Collections of the Library of Congress, U.S. Involvement Before 1913". Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 July 2019. ^ "Punitive Expedition in Mexico, 1916–1917". U.S. Department of State archive. 20 January 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2019. ^ "ZIMMERMANN TELEGRAM". The National WWI Museum and Memorial. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2019. ^ Rafael Hernández Ángeles. "85º ANIVERSARIO DE LA FUNDACIÓN DEL PARTIDO NACIONAL REVOLUCIONARIO (PNR)" [85th anniversary of the founding of the National Revolutionary Party (PRN)]. Instituto Nacional de Estudios Historicos de las Revoluciones de Mexico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019. ^ "The Mexican Miracle: 1940–1968". World History from 1500. Emayzine. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007. ^ Elena Poniatowska (1975). Massacre in Mexico. Viking, New York. ISBN 978-0-8262-0817-0. ^ Kennedy, Duncan (19 July 2008). "Mexico's long forgotten dirty war". BBC News. Retrieved 17 July 2013. ^ Krauze, Enrique (January–February 2006). "Furthering Democracy in Mexico". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 January 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2007. {{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires |magazine= (help) ^ Schedler, Andreas (2006). Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. L. Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58826-440-4. ^ Crandall, R.; Paz and Roett (2004). "Mexico's Domestic Economy: Policy Options and Choices". Mexico's Democracy at Work. Lynne Reinner Publishers. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8018-5655-6. ^ ""Mexico The 1988 Elections" (Sources: The Library of the Congress Country Studies, CIA World Factbook)". Photius Coutsoukis. Retrieved 30 May 2010. ^ Gomez Romero, Luis (5 October 2018). "Massacres, disappearances and 1968: Mexicans remember the victims of a 'perfect dictatorship'". The Conversation. ^ "Vargas Llosa: "México es la dictadura perfecta"". El País. 1 September 1990. ^ Reding, Andrew (1991). "Mexico: The Crumbling of the "Perfect Dictatorship"". World Policy Journal. 8 (2): 255–284. JSTOR 40209208. ^ Cruz Vasconcelos, Gerardo. "Desempeño Histórico 1914–2004" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2007. ^ Valles Ruiz, Rosa María (June 2016). "Elecciones presidenciales 2006 en México. La perspectiva de la prensa escrita" [2006 presidential Elections in Mexico. The Perspective of the Press]. Revista mexicana de opinión pública (in Spanish) (20): 31–51. ^ Reséndiz, Francisco (2006). "Rinde AMLO protesta como "presidente legítimo"". El Universal (in Spanish). ^ "Enrique Pena Nieto wins Mexican presidential election". The Telegraph. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2015. ^ Sieff, Kevin. "López Obrador, winner of Mexican election, given broad mandate". Washington Post. ^ Sharma, Gaurav (10 May 2018). "Mexico's Oil And Gas Industry Privatization Efforts Nearing Critical Phase". Forbes. Retrieved 4 June 2020. ^ Barrera Diaz, Cyntia; Villamil, Justin; Still, Amy (14 February 2020). "Pemex Ex-CEO Arrest Puts AMLO in Delicate Situation". Rigzone. Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 June 2020. ^ "Mexico's presidential front runner on high alert for election fraud ahead of Sunday's vote". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. 30 June 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2020. ^ "Mexico's 2018 Elections: Results and Potential Implications" (PDF). fas.org. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2021. ^ "Mexico's López Obrador sworn in as first leftist president in decades". BBC News. 2 December 2018. ^ Karol Suarez, Rafael Romo and Joshua Berlinger. "Mexico's President loses grip on power in midterm elections marred by violence". CNN.

- Stay safe

Mounted tourist police, Mexico City

Mounted tourist police, Mexico City WARNING: Avoid travelling to the following states: Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima, Sinaloa and Tamaulipas...Read moreStay safeRead less

WARNING: Avoid travelling to the following states: Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima, Sinaloa and Tamaulipas...Read moreStay safeRead less Mounted tourist police, Mexico City

Mounted tourist police, Mexico City WARNING: Avoid travelling to the following states: Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima, Sinaloa and Tamaulipas

WARNING: Avoid travelling to the following states: Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima, Sinaloa and Tamaulipas

The U.S. government recommends against traveling to the five states mentioned above because of high levels of crime and drug-related violence. Law enforcement's ability to respond to incidents in those states are generally limited.The Mexican government makes a considerable effort to protect visitors to major tourist destinations, and resort areas and tourist destinations in Mexico generally do not see the levels of drug-related violence and crime reported in the border region and in areas along major trafficking routes.

Government travel advisories(Information last updated 29 Aug 2020)United StatesMexico has a reputation for being a dangerous country — a reputation that's not entirely unwarranted, but the average traveller should not be too overly concerned or cautious of their surroundings. A lot of the crime occurs between those involved in the drug trade (See drug traffic issues for more information), which doesn't affect tourists at all.

In most of the cities, location is very important as security changes from place to place. Areas close to downtown (centro) are safer to walk at night, especially on the "Plaza", "Zócalo" or "Jardín" (main square) and areas nearby. Stay in populated areas, avoid poor neighborhoods, especially at night, and don't walk there at any time if you are alone. Vicious beatings have been reported at resorts by people who have travelled alone, so stay alert for any suspicious-looking individual. If you wish to visit one of the slums, you should only go as part of a guided tour with a reputable guide or tour company.

Political violence in Chiapas and Oaxaca has abated, and is far less of a threat than drug-related crime. However, Mexican authorities do not look approvingly on foreigners who participate in demonstrations (even peaceful ones) or voice support for groups such as the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional and its leader, Subcomandante Marcos, even if their images and slogans are commonly sold on t-shirts and caps in markets.

Do not wave cash or credit cards around. Use them discreetly and put them away as quickly as possible.

The nationwide emergency number is 911. Although Mexico has one of the largest police forces in the world, systemic corruption and low salaries often restrict the capabilities of law enforcement. Enlisting the help of the police almost always requires solid Spanish-language skills.

Beggars are not usually a threat, but you will find lots in urban areas. Avoid being surrounded by them, as some can pickpocket your goods. Giving away two pesos quickly can get you out of such troubles (but may also attract other beggars). Most poor and homeless Mexicans prefer to sell trinkets, gum, sing, or provide some meager service than beg outright.

In other cities, such as Guadalajara and Mexico City, are safer than most places in Mexico. However, caution is still recommended.

Drug traffic issues States with the most conflict, marked in red (2010)

States with the most conflict, marked in red (2010)Felipe Calderon, one of the country's previous presidents, waged war on the drug cartels, and in turn, they have waged war in turn against the government (and more often, among each other).

Some Mexican northern and border cities such as Tijuana, Nogales, Nuevo Laredo, Chihuahua, Culiacán, Durango, and Juárez can be dangerous if you are not familiar with them, especially at night. Most crime in the northern cities is related to the drug trade and/or police corruption. However, since law enforcement figures are so overwhelmed or involved in drug-related activities, many northern border towns that were previously somewhat dangerous to begin with are now a hotbed for criminals to act with impunity. Ciudad Juárez, in particular, bears the brunt of this violence, and with nearly a fourth of Mexico's overall murders, travel there requires special attention.

Away from the northern states, cartel related violence is centered in specific areas, including the Pacific Coast states of Michoacán and Guerrero. However, exercise caution in any major city, especially at night or in high crime areas.

As aforementioned, tourists and travellers are of no interest to the drug cartels. Many popular tourist destinations like Oaxaca, Guanajuato, Los Cabos, Mexico City, Puerto Vallarta, Cancún, Mérida and Guadalajara are largely unaffected by this, simply because there are no borders there. Ciudad Juárez is a primary battleground in the drug war, and while foreign travellers are not often targeted, the presence of two warring cartels, many small opportunistic gangs, and armed police and soldiers has created a chaotic situation to say the least.

Although rarely surprising, the drug violence's new victim is Monterrey. The city at one point was crowned the safest city in Latin America, and the hard-working environment and entrepreneurial spirit was what defined the city for most Mexicans. Today, it has been the latest city to fall into the hands of the drug gangs, and deadly shootouts exist even in broad daylight. People have been kidnapped in very high profile hotels, and while the city is still not mirroring Ciudad Juarez, it does not lag far behind.

As a general rule of thumb, the further away you are from the north, and the closer you are to Mexico City, the safer you'll be. Many people go to Mexico City to seek refuge from drug-related violence as many politicians and military personnel are there.

Consumption of drugs is not recommended while you are in Mexico because consumption in public areas will get you a fine and will most likely get you in trouble with the police. The army also sets up random checkpoints throughout all major highways in search of narcotics and weapons. Drug consumption is also frowned upon by a large percentage of the population.

Advice for the beachJellyfish stings: vinegar or mustard on the skin, take some to the beach with you.

Stingray stings: water as hot as you can bear – the heat deactivates the poison.

Sunburns: Bring sunscreen if going to beaches because you might not find it available in some areas.

Riptides: Very dangerous, particularly during and after storms

Public transportationWhen in major cities – especially Mexico City – is better to play it safe with taxis. The best options are to phone a taxi company, to request that your hotel or restaurant call a taxi for you, or to pick up a taxi from an established post (Taxi de Sitio). Also, taxis can be stopped in the middle of the street, which is okay for most of the country, but particularly unsafe in Mexico City.