Christianity

Context of Christianity

Read more

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.4 billion followers representing one-third of the global population. Its adherents, known as Christians, are estimated to make up a majority of the population in 157 countries and territories. Most Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, whose coming as the Messiah was prophesied in the Old Testament (the Hebrew Bible) and chronicled in the New Testament, published together as the Christian biblical canon.

Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, as well as in its doctrines concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology. The creeds of various Christian denominations generally hold in common Jesus as the Son of God—the Logos incarnated—who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but rose from the dead for the salvation of mankind; and referred to as the gospel, meaning the "good news". Describing Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, with the Old Testament as the gospel's respected background.

Christianity began in the 1st century after the birth of Jesus as a Judaic sect with Hellenistic influence, in the Roman province of Judea. The disciples of Jesus spread their faith around the Eastern Mediterranean area, despite significant persecution. The inclusion of Gentiles led Christianity to slowly separate from Judaism (2nd century). Emperor Constantine the Great decriminalized Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan (313), later convening the Council of Nicaea (325) where Early Christianity was consolidated into what would become the State church of the Roman Empire (380). The Church of the East and Oriental Orthodoxy both split over differences in Christology (5th century), while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church separated in the East–West Schism (1054). Protestantism split in numerous denominations from the Catholic Church in the Reformation era (16th century). Following the Age of Discovery (15th–17th century), Christianity expanded throughout the world via missionary work, extensive trade and colonialism. Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, particularly in Europe from late antiquity and the Middle Ages.

The six major branches of Christianity are Roman Catholicism (1.3 billion people), Protestantism (800 million), Eastern Orthodoxy (220 million), Oriental Orthodoxy (60 million), Restorationism (35 million), and the Church of the East (600 thousand). Smaller church communities number in the thousands despite efforts toward unity (ecumenism). In the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion even with a decline in adherence, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian. Christianity is growing in Africa and Asia, the world's most populous continents. Christians remain greatly persecuted in many regions of the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia, and South Asia.

More about Christianity

- Early Christianity Apostolic Age

Read moreEarly Christianity Apostolic AgeRead less

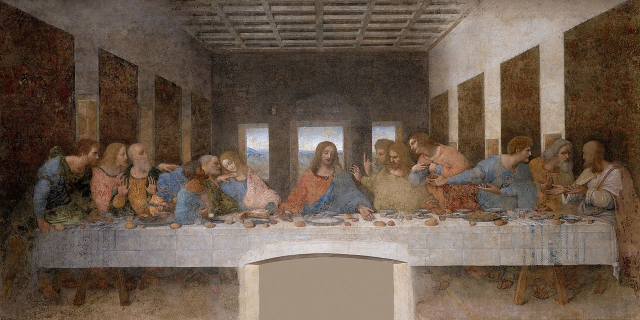

Read moreEarly Christianity Apostolic AgeRead less The Cenacle on Mount Zion in Jerusalem, claimed to be the location of the Last Supper and Pentecost

The Cenacle on Mount Zion in Jerusalem, claimed to be the location of the Last Supper and PentecostChristianity developed during the 1st century AD as a Jewish Christian sect with Hellenistic influence[1] of Second Temple Judaism.[2][3] An early Jewish Christian community was founded in Jerusalem under the leadership of the Pillars of the Church, namely James the Just, the brother of Jesus, Peter, and John.[4]

Jewish Christianity soon attracted Gentile God-fearers, posing a problem for its Jewish religious outlook, which insisted on close observance of the Jewish commandments. Paul the Apostle solved this by insisting that salvation by faith in Christ, and participation in his death and resurrection by their baptism, sufficed.[5] At first he persecuted the early Christians, but after a conversion experience he preached to the gentiles, and is regarded as having had a formative effect on the emerging Christian identity as separate from Judaism. Eventually, his departure from Jewish customs would result in the establishment of Christianity as an independent religion.[6]

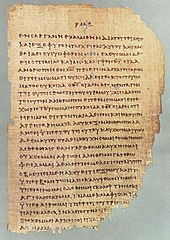

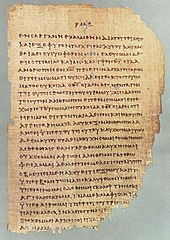

Ante-Nicene period A folio from Papyrus 46, an early-3rd-century collection of Pauline epistles

A folio from Papyrus 46, an early-3rd-century collection of Pauline epistlesThis formative period was followed by the early bishops, whom Christians consider the successors of Christ's apostles. From the year 150, Christian teachers began to produce theological and apologetic works aimed at defending the faith. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and the study of them is called patristics. Notable early Fathers include Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria and Origen.

Persecution of Christians occurred intermittently and on a small scale by both Jewish and Roman authorities, with Roman action starting at the time of the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. Examples of early executions under Jewish authority reported in the New Testament include the deaths of Saint Stephen[7] and James, son of Zebedee.[8] The Decian persecution was the first empire-wide conflict,[9] when the edict of Decius in 250 AD required everyone in the Roman Empire (except Jews) to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods. The Diocletianic Persecution beginning in 303 AD was also particularly severe. Roman persecution ended in 313 AD with the Edict of Milan.

While Proto-orthodox Christianity was becoming dominant, heterodox sects also existed at the same time, which held radically different beliefs. Gnostic Christianity developed a duotheistic doctrine based on illusion and enlightenment rather than forgiveness of sin. With only a few scriptures overlapping with the developing orthodox canon, most Gnostic texts and Gnostic gospels were eventually considered heretical and suppressed by mainstream Christians. A gradual splitting off of Gentile Christianity left Jewish Christians continuing to follow the Law of Moses, including practices such as circumcision. By the fifth century, they and the Jewish–Christian gospels would be largely suppressed by the dominant sects in both Judaism and Christianity.

Spread and acceptance in Roman Empire The Monastery of St. Matthew, located atop Mount Alfaf in northern Iraq, is recognized as one of the oldest Christian monasteries in existence.[10]

The Monastery of St. Matthew, located atop Mount Alfaf in northern Iraq, is recognized as one of the oldest Christian monasteries in existence.[10]Christianity spread to Aramaic-speaking peoples along the Mediterranean coast and also to the inland parts of the Roman Empire and beyond that into the Parthian Empire and the later Sasanian Empire, including Mesopotamia, which was dominated at different times and to varying extents by these empires.[11] The presence of Christianity in Africa began in the middle of the 1st century in Egypt and by the end of the 2nd century in the region around Carthage. Mark the Evangelist is claimed to have started the Church of Alexandria in about 43 AD; various later churches claim this as their own legacy, including the Coptic Orthodox Church.[12][13][14] Important Africans who influenced the early development of Christianity include Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius, and Augustine of Hippo.

The 7th-century Khor Virap monastery in the shadow of Mount Ararat; Armenia was the first state to adopt Christianity as the state religion, in AD 301.[15]

The 7th-century Khor Virap monastery in the shadow of Mount Ararat; Armenia was the first state to adopt Christianity as the state religion, in AD 301.[15]King Tiridates III made Christianity the state religion in Armenia between 301 and 314,[15][16][17] thus Armenia became the first officially Christian state. It was not an entirely new religion in Armenia, having penetrated into the country from at least the third century, but it may have been present even earlier.[18]

Constantine I was exposed to Christianity in his youth, and throughout his life his support for the religion grew, culminating in baptism on his deathbed.[19] During his reign, state-sanctioned persecution of Christians was ended with the Edict of Toleration in 311 and the Edict of Milan in 313. At that point, Christianity was still a minority belief, comprising perhaps only five percent of the Roman population.[20] Influenced by his adviser Mardonius, Constantine's nephew Julian unsuccessfully tried to suppress Christianity.[21] On 27 February 380, Theodosius I, Gratian, and Valentinian II established Nicene Christianity as the State church of the Roman Empire.[22] As soon as it became connected to the state, Christianity grew wealthy; the Church solicited donations from the rich and could now own land.[23]

Constantine was also instrumental in the convocation of the First Council of Nicaea in 325, which sought to address Arianism and formulated the Nicene Creed, which is still used by in Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and many other Protestant churches.[24][25] Nicaea was the first of a series of ecumenical councils, which formally defined critical elements of the theology of the Church, notably concerning Christology.[26] The Church of the East did not accept the third and following ecumenical councils and is still separate today by its successors (Assyrian Church of the East).

In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the Byzantine Empire was one of the peaks in Christian history and Christian civilization,[27] and Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in size, wealth, and culture.[28] There was a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy, as well as an increase in literary output in vernacular Greek.[29] Byzantine art and literature held a preeminent place in Europe, and the cultural impact of Byzantine art on the West during this period was enormous and of long-lasting significance.[30] The later rise of Islam in North Africa reduced the size and numbers of Christian congregations, leaving in large numbers only the Coptic Church in Egypt, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church in the Horn of Africa and the Nubian Church in the Sudan (Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia).

Middle Ages Early Middle Ages Christendom by AD 600 after its spread to Africa and Europe from the Middle East

Christendom by AD 600 after its spread to Africa and Europe from the Middle EastWith the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the West, the papacy became a political player, first visible in Pope Leo's diplomatic dealings with Huns and Vandals.[31] The church also entered into a long period of missionary activity and expansion among the various tribes. While Arianists instituted the death penalty for practicing pagans (see the Massacre of Verden, for example), what would later become Catholicism also spread among the Hungarians, the Germanic,[31] the Celtic, the Baltic and some Slavic peoples.

Around 500, Christianity was thoroughly integrated into Byzantine and Kingdom of Italy culture[32] and Benedict of Nursia set out his Monastic Rule, establishing a system of regulations for the foundation and running of monasteries.[31] Monasticism became a powerful force throughout Europe,[31] and gave rise to many early centers of learning, most famously in Ireland, Scotland, and Gaul, contributing to the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century.

In the 7th century, Muslims conquered Syria (including Jerusalem), North Africa, and Spain, converting some of the Christian population to Islam, and placing the rest under a separate legal status. Part of the Muslims' success was due to the exhaustion of the Byzantine Empire in its decades long conflict with Persia.[33] Beginning in the 8th century, with the rise of Carolingian leaders, the Papacy sought greater political support in the Frankish Kingdom.[34]

The Middle Ages brought about major changes within the church. Pope Gregory the Great dramatically reformed the ecclesiastical structure and administration.[35] In the early 8th century, iconoclasm became a divisive issue, when it was sponsored by the Byzantine emperors. The Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (787) finally pronounced in favor of icons.[36] In the early 10th century, Western Christian monasticism was further rejuvenated through the leadership of the great Benedictine monastery of Cluny.[37]

High and Late Middle Ages An example of Byzantine pictorial art, the Deësis mosaic at the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople

An example of Byzantine pictorial art, the Deësis mosaic at the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont, where he preached the First Crusade. Illustration by Jean Colombe from the Passages d'outremer, c. 1490.

Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont, where he preached the First Crusade. Illustration by Jean Colombe from the Passages d'outremer, c. 1490.In the West, from the 11th century onward, some older cathedral schools became universities (see, for example, University of Oxford, University of Paris and University of Bologna). Previously, higher education had been the domain of Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools (Scholae monasticae), led by monks and nuns. Evidence of such schools dates back to the 6th century CE.[38] These new universities expanded the curriculum to include academic programs for clerics, lawyers, civil servants, and physicians.[39] The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting.[40][41][42]

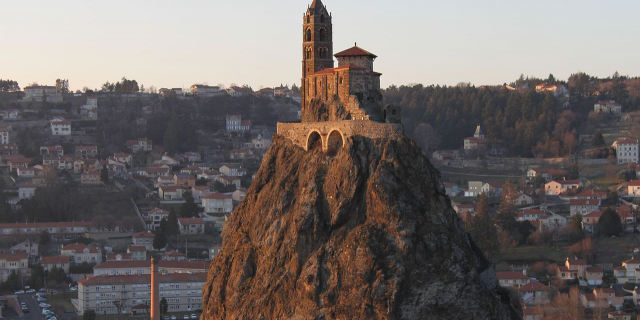

Accompanying the rise of the "new towns" throughout Europe, mendicant orders were founded, bringing the consecrated religious life out of the monastery and into the new urban setting. The two principal mendicant movements were the Franciscans[43] and the Dominicans,[44] founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic, respectively. Both orders made significant contributions to the development of the great universities of Europe. Another new order was the Cistercians, whose large isolated monasteries spearheaded the settlement of former wilderness areas. In this period, church building and ecclesiastical architecture reached new heights, culminating in the orders of Romanesque and Gothic architecture and the building of the great European cathedrals.[45]

Christian nationalism emerged during this era in which Christians felt the impulse to recover lands in which Christianity had historically flourished.[46] From 1095 under the pontificate of Urban II, the First Crusade was launched.[47] These were a series of military campaigns in the Holy Land and elsewhere, initiated in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I for aid against Turkish expansion. The Crusades ultimately failed to stifle Islamic aggression and even contributed to Christian enmity with the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.[48]

The Christian Church experienced internal conflict between the 7th and 13th centuries that resulted in a schism between the so-called Latin or Western Christian branch (the Catholic Church),[49] and an Eastern, largely Greek, branch (the Eastern Orthodox Church). The two sides disagreed on a number of administrative, liturgical and doctrinal issues, most prominently Eastern Orthodox opposition to papal supremacy.[50][51] The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) attempted to reunite the churches, but in both cases, the Eastern Orthodox refused to implement the decisions, and the two principal churches remain in schism to the present day. However, the Catholic Church has achieved union with various smaller eastern churches.

In the thirteenth century, a new emphasis on Jesus' suffering, exemplified by the Franciscans' preaching, had the consequence of turning worshippers' attention towards Jews, on whom Christians had placed the blame for Jesus' death. Christianity's limited tolerance of Jews was not new—Augustine of Hippo said that Jews should not be allowed to enjoy the citizenship that Christians took for granted—but the growing antipathy towards Jews was a factor that led to the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290, the first of many such expulsions in Europe.[52][53]

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against Cathar heresy,[54] various institutions, broadly referred to as the Inquisition, were established with the aim of suppressing heresy and securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion and prosecution.[55]

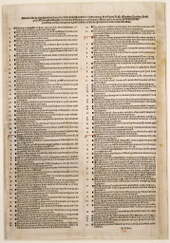

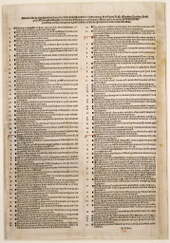

Modern era Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation Martin Luther initiated the Reformation with his Ninety-five Theses in 1517.

Martin Luther initiated the Reformation with his Ninety-five Theses in 1517.The 15th-century Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. During the Reformation, Martin Luther posted the Ninety-five Theses 1517 against the sale of indulgences.[56] Printed copies soon spread throughout Europe. In 1521 the Edict of Worms condemned and excommunicated Luther and his followers, resulting in the schism of the Western Christendom into several branches.[57]

Other reformers like Zwingli, Oecolampadius, Calvin, Knox, and Arminius further criticized Catholic teaching and worship. These challenges developed into the movement called Protestantism, which repudiated the primacy of the pope, the role of tradition, the seven sacraments, and other doctrines and practices.[56] The Reformation in England began in 1534, when King Henry VIII had himself declared head of the Church of England. Beginning in 1536, the monasteries throughout England, Wales and Ireland were dissolved.[58]

Thomas Müntzer, Andreas Karlstadt and other theologians perceived both the Catholic Church and the confessions of the Magisterial Reformation as corrupted. Their activity brought about the Radical Reformation, which gave birth to various Anabaptist denominations.

Michelangelo's 1498–99 Pietà in St. Peter's Basilica; the Catholic Church was among the patronages of the Renaissance.[59][60][61]

Michelangelo's 1498–99 Pietà in St. Peter's Basilica; the Catholic Church was among the patronages of the Renaissance.[59][60][61]Partly in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church engaged in a substantial process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reform.[62] The Council of Trent clarified and reasserted Catholic doctrine. During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states.[63]

Meanwhile, the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 brought about a new wave of missionary activity. Partly from missionary zeal, but under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Throughout Europe, the division caused by the Reformation led to outbreaks of religious violence and the establishment of separate state churches in Europe. Lutheranism spread into the northern, central, and eastern parts of present-day Germany, Livonia, and Scandinavia. Anglicanism was established in England in 1534. Calvinism and its varieties, such as Presbyterianism, were introduced in Scotland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland, and France. Arminianism gained followers in the Netherlands and Frisia. Ultimately, these differences led to the outbreak of conflicts in which religion played a key factor. The Thirty Years' War, the English Civil War, and the French Wars of Religion are prominent examples. These events intensified the Christian debate on persecution and toleration.[64]

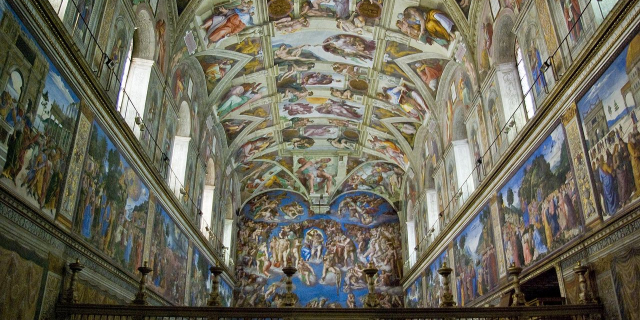

In the revival of neoplatonism Renaissance humanists did not reject Christianity; quite the contrary, many of the greatest works of the Renaissance were devoted to it, and the Catholic Church patronized many works of Renaissance art.[65] Much, if not most, of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Church.[65] Some scholars and historians attribute Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution.[66] Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Nicolaus Copernicus,[67] Galileo Galilei,[68] Johannes Kepler,[69] Isaac Newton[70] and Robert Boyle.[71]

Post-Enlightenment A depiction of Madonna and Child in a 19th-century Kakure Kirishitan Japanese woodcut

A depiction of Madonna and Child in a 19th-century Kakure Kirishitan Japanese woodcutIn the era known as the Great Divergence, when in the West, the Age of Enlightenment and the scientific revolution brought about great societal changes, Christianity was confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies, such as versions of socialism and liberalism.[72] Events ranged from mere anti-clericalism to violent outbursts against Christianity, such as the dechristianization of France during the French Revolution,[73] the Spanish Civil War, and certain Marxist movements, especially the Russian Revolution and the persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union under state atheism.[74][75][76][77]

Especially pressing in Europe was the formation of nation states after the Napoleonic era. In all European countries, different Christian denominations found themselves in competition to greater or lesser extents with each other and with the state. Variables were the relative sizes of the denominations and the religious, political, and ideological orientation of the states. Urs Altermatt of the University of Fribourg, looking specifically at Catholicism in Europe, identifies four models for the European nations. In traditionally Catholic-majority countries such as Belgium, Spain, and Austria, to some extent, religious and national communities are more or less identical. Cultural symbiosis and separation are found in Poland, the Republic of Ireland, and Switzerland, all countries with competing denominations. Competition is found in Germany, the Netherlands, and again Switzerland, all countries with minority Catholic populations, which to a greater or lesser extent identified with the nation. Finally, separation between religion (again, specifically Catholicism) and the state is found to a great degree in France and Italy, countries where the state actively opposed itself to the authority of the Catholic Church.[78]

The combined factors of the formation of nation states and ultramontanism, especially in Germany and the Netherlands, but also in England to a much lesser extent,[79] often forced Catholic churches, organizations, and believers to choose between the national demands of the state and the authority of the Church, specifically the papacy. This conflict came to a head in the First Vatican Council, and in Germany would lead directly to the Kulturkampf.[80]

Ordination of new pastors in Cameroon, 2014

Ordination of new pastors in Cameroon, 2014Christian commitment in Europe dropped as modernity and secularism came into their own,[81] particularly in the Czech Republic and Estonia,[82] while religious commitments in America have been generally high in comparison to Europe. Changes in worldwide Christianity over the last century have been significant, since 1900, Christianity has spread rapidly in the Global South and Third World countries.[83] The late 20th century has shown the shift of Christian adherence to the Third World and the Southern Hemisphere in general,[84][85] with the West no longer the chief standard bearer of Christianity. Approximately 7 to 10% of Arabs are Christians,[86] most prevalent in Egypt, Syria and Lebanon.

^ "Evodius of Antioch → Antioch, Church of". Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity Online. doi:10.1163/2589-7993_eeco_dum_00001220. Retrieved 14 March 2022. ^ Cory, Catherine (13 August 2015). Christian Theological Tradition. Routledge. p. 20 and forwards. ISBN 978-1-317-34958-7. ^ Benko, Stephen (1984). Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Indiana University Press. p. 22 and forwards. ISBN 978-0-253-34286-7. ^ McGrath, Alister E. (2006), Christianity: An Introduction, Wiley-Blackwell, p. 174, ISBN 1-4051-0899-1 ^ Seifrid, Mark A. (1992). "'Justification by Faith' and The Disposition of Paul's Argument". Justification by Faith: The Origin and Development of a Central Pauline Theme. Novum Testamentum. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 210–211, 246–247. ISBN 90-04-09521-7. ISSN 0167-9732. ^ Wylen, Stephen M., The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction, Paulist Press (1995), ISBN 0-8091-3610-4, Pp. 190–192.; Dunn, James D.G., Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, A.D. 70 to 135, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (1999), ISBN 0-8028-4498-7, Pp. 33–34.; Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro & Gargola, Daniel J & Talbert, Richard John Alexander, The Romans: From Village to Empire, Oxford University Press (2004), ISBN 0-19-511875-8, p. 426. ^ Acts 7:59 ^ Acts 12:2 ^ Martin, D. 2010. The "Afterlife" of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation Archived 8 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine (lecture transcript Archived 12 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine). Yale University. ^ "Monastère de Mor Mattai – Mossul – Irak" (in French). Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. ^ Michael Whitby, et al. eds. Christian Persecution, Martyrdom and Orthodoxy (2006) online edition ^ Eusebius of Caesarea, the author of Ecclesiastical History in the 4th century, states that St. Mark came to Egypt in the first or third year of the reign of Emperor Claudius, i.e. 41 or 43 AD. "Two Thousand years of Coptic Christianity" Otto F.A. Meinardus p. 28. ^ Lettinga, Neil. "A History of the Christian Church in Western North Africa". Archived from the original on 30 July 2001. ^ "Allaboutreligion.org". Allaboutreligion.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010. ^ a b Gill, N.S. "Which Nation First Adopted Christianity?". About.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011. Armenia is considered the first nation to have adopted Christianity as the state religion in a traditional date of c. A.D. 301. ^ "Armenia". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 8 October 2011. (Archived 2011 edition) ^ Brunner, Borgna (2006). Time Almanac with Information Please 2007. New York: Time Home Entertainment. p. 685. ISBN 978-1-933405-49-0. ^ Theo Maarten van Lint (2009). "The Formation of Armenian Identity in the First Millennium". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1/3): 269. ^ Harris, Jonathan (2017). Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4742-5467-0. ^ Chidester, David (2000). Christianity: A Global History. HarperOne. p. 91. ^ Ricciotti 1999 ^ Theodosian Code XVI.i.2, in: Bettenson. Documents of the Christian Church. p. 31. ^ Burbank, Jane; Copper, Frederick (2010). Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 64. ^ McTavish, T. J. (2010). A Theological Miscellany: 160 Pages of Odd, Merry, Essentially Inessential Facts, Figures, and Tidbits about Christianity. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-4185-5281-7. The Nicene Creed, as used in the churches of the West (Anglican, Catholic, Lutheran, and others), contains the statement, "We believe [or I believe] in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son." ^ Cite error: The named reference UMC—Our Common Heritage as Christians was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ McManners, Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity, pp. 37ff. ^ Cameron 2006, p. 42. ^ Cameron 2006, p. 47. ^ Browning 1992, pp. 198–208. ^ Browning 1992, p. 218. ^ a b c d González 1984, pp. 238–242 ^ Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Translated by Harari, Yuval Noah; Purcell, John; Watzman, Haim. London: Penguin Random House UK. pp. 243, 247. ISBN 978-0-09-959008-8. OCLC 910498369. ^ Mullin 2008, p. 88. ^ Mullin 2008, pp. 93–94. ^ González 1984, pp. 244–47 ^ González 1984, p. 260 ^ González 1984, pp. 278–281 ^ Riché, Pierre (1978): "Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century", Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-376-8, pp. 126–127, 282–298 ^ Rudy, The Universities of Europe, 1100–1914, p. 40 ^ Verger, Jacques [in French] (1999). Culture, enseignement et société en Occident aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles (in French) (1st ed.). Presses universitaires de Rennes in Rennes. ISBN 978-2-86847-344-8. Retrieved 17 June 2014. ^ Verger, Jacques. "The Universities and Scholasticism," in The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume V c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 257. ^ Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX ^ González 1984, pp. 303–307, 310ff., 384–386 ^ González 1984, pp. 305, 310ff., 316ff ^ González 1984, pp. 321–323, 365ff ^ Parole de l'Orient, Volume 30. Université Saint-Esprit. 2005. p. 488. ^ González 1984, pp. 292–300 ^ Riley-Smith. The Oxford History of the Crusades. ^ The Western Church was called Latin at the time by the Eastern Christians and non-Christians due to its conducting of its rituals and affairs in the Latin language ^ "The Great Schism: The Estrangement of Eastern and Western Christendom". Orthodox Information Centre. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2007. ^ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), p. 91 ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2011). Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-18999-3. ^ Telushkin, Joseph (2008). Jewish Literacy. HarperCollins. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-0-688-08506-3. ^ González 1984, pp. 300, 304–305 ^ González 1984, pp. 310, 383, 385, 391 ^ a b Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. pp. 39, 55–61. ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. p. 7. ^ Schama. A History of Britain. pp. 306–310. ^ National Geographic, 254. ^ Jensen, De Lamar (1992), Renaissance Europe, ISBN 0-395-88947-2 ^ Levey, Michael (1967). Early Renaissance. Penguin Books. ^ Bokenkotter 2004, pp. 242–244. ^ Simon. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. pp. 109–120. ^ A general overview about the English discussion is given in Coffey, Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England 1558–1689. ^ a b Open University, Looking at the Renaissance: Religious Context in the Renaissance (Retrieved 10 May 2007) ^ Some scholars and historians attribute Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution: Harrison, Peter (8 May 2012). "Christianity and the rise of western science". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 August 2014. Noll, Mark, Science, Religion, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Science and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015 Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (1986), "Introduction", God & Nature: Historical Essays on the Encounter Between Christianity and Science, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 5, 12, ISBN 978-0-520-05538-4 Gilley, Sheridan (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 8, World Christianities C.1815-c.1914. Brian Stanley. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-521-81456-1. Lindberg, David. (1992) The Beginnings of Western Science University of Chicago Press. p. 204. ^ Pro forma candidate to Prince-Bishop of Warmia, cf. Dobrzycki, Jerzy, and Leszek Hajdukiewicz, "Kopernik, Mikołaj", Polski słownik biograficzny (Polish Biographical Dictionary), vol. XIV, Wrocław, Polish Academy of Sciences, 1969, p. 11. ^ Sharratt, Michael (1994). Galileo: Decisive Innovator. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17, 213. ISBN 0-521-56671-1. ^ "Because he would not accept the Formula of Concord without some reservations, he was excommunicated from the Lutheran communion. Because he remained faithful to his Lutheranism throughout his life, he experienced constant suspicion from Catholics." John L. Treloar, "Biography of Kepler shows man of rare integrity. Astronomer saw science and spirituality as one." National Catholic Reporter, 8 October 2004, p. 2a. A review of James A. Connor Kepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order amid Religious War, Political Intrigue and Heresy Trial of His Mother, Harper San Francisco. ^ Richard S. Westfall – Indiana University The Galileo Project. (Rice University). Retrieved 5 July 2008. ^ "The Boyle Lecture". St. Marylebow Church. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2022. ^ Novak, Michael (1988). Catholic social thought and liberal institutions: Freedom with justice. Transaction. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-88738-763-0. ^ Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience (vol. 2) chapter 21. ^ Religion and the State in Russia and China: Suppression, Survival, and Revival, by Christopher Marsh, p. 47. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011. ^ Inside Central Asia: A Political and Cultural History, by Dilip Hiro. Penguin, 2009. ^ Adappur, Abraham (2000). Religion and the Cultural Crisis in India and the West. Intercultural Publications. ISBN 978-81-85574-47-9. Forced Conversion under Atheistic Regimes: It might be added that the most modern example of forced "conversions" came not from any theocratic state, but from a professedly atheist government—that of the Soviet Union under the Communists. ^ Geoffrey Blainey 2011). A Short History of Christianity; Viking; p. 494 ^ Altermatt, Urs (2007). "Katholizismus und Nation: Vier Modelle in europäisch-vergleichender Perspektive". In Urs Altermatt, Franziska Metzger (ed.). Religion und Nation: Katholizismen im Europa des 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (in German). Kohlhammer Verlag. pp. 15–34. ISBN 978-3-17-019977-4. ^ Heimann, Mary (1995). Catholic Devotion in Victorian England. Clarendon Press. pp. 165–73. ISBN 978-0-19-820597-5. ^ The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History Helmut Walser Smith, p. 360, OUP Oxford, 29 September 2011 ^ "Religion may become extinct in nine nations, study says". BBC News. 22 March 2011. ^ "図録▽世界各国の宗教". .ttcn.ne.jp. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012. ^ Jenkins, Philip (2011). "The Rise of the New Christianity". The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 101–133. ISBN 9780199767465. LCCN 2010046058. ^ Kim, Sebastian; Kim, Kirsteen (2008). Christianity as a World Religion. London: Continuum. p. 2. ^ Hanciles, Jehu (2008). Beyond Christendom: Globalization, African Migration, and the Transformation of the West. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-103-1. ^ Fargues, Philippe (1998). "A Demographic Perspective". In Pacini, Andrea (ed.). Christian Communities in the Middle East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829388-0.