Ephesus (; Greek: Ἔφεσος, translit. Éphesos; Turkish: Efes; may ultimately derive from Hittite: 𒀀𒉺𒊭, romanized: Apaša) was a city in Ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital, by Attic and Ionian Greeks. During the Classical Greek era, it was one of twelve cities that were members of the Ionian League. The city came under the control of the Roman Republic in 129 BC.

The city was famous in its day...Read more

Ephesus (; Greek: Ἔφεσος, translit. Éphesos; Turkish: Efes; may ultimately derive from Hittite: 𒀀𒉺𒊭, romanized: Apaša) was a city in Ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital, by Attic and Ionian Greeks. During the Classical Greek era, it was one of twelve cities that were members of the Ionian League. The city came under the control of the Roman Republic in 129 BC.

The city was famous in its day for the nearby Temple of Artemis (completed around 550 BC), which has been designated one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Its many monumental buildings included the Library of Celsus and a theatre capable of holding 24,000 spectators.

Ephesus was a recipient city of one of the Pauline epistles and one of the seven churches of Asia addressed in the Book of Revelation. The Gospel of John may have been written there. and it was the site of several 5th-century Christian Councils (see Council of Ephesus). The city was destroyed by the Goths in 263. Although it was afterwards rebuilt, its importance as a commercial centre declined as the harbour was slowly silted up by the Küçükmenderes River. In 614, it was partially destroyed by an earthquake.

Today, the ruins of Ephesus are a favourite international and local tourist attraction, being accessible from Adnan Menderes Airport and from the resort town Kuşadası. In 2015, the ruins were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Humans had begun inhabiting the area surrounding Ephesus by the Neolithic Age (about 6000 BC), as shown by evidence from excavations at the nearby höyük (artificial mounds known as tells) of Arvalya and Cukurici.[1][2]

Bronze AgeExcavations in recent years have unearthed settlements from the early Bronze Age at Ayasuluk Hill. According to Hittite sources, the capital of the kingdom of Arzawa (another independent state in Western and Southern Anatolia/Asia Minor[3]) was Apasa (or Abasa), and some scholars suggest that this is the same place the Greeks later called Ephesus.[4][5][6][7] In 1954, a burial ground from the Mycenaean era (1500–1400 BC), which contained ceramic pots, was discovered close to the ruins of the basilica of St. John.[8] This was the period of the Mycenaean expansion, a process that continued into the 13th century BC. The names Apasa and Ephesus appear to be cognate,[9] and recently found inscriptions seem to pinpoint the places in the Hittite record.[10][11]

Period of Greek migrations Site of the Temple of Artemis in the town of Selçuk, near Ephesus.

Site of the Temple of Artemis in the town of Selçuk, near Ephesus.Ephesus was founded as an Attic-Ionian colony in the 10th century BC on a hill (now known as the Ayasuluk Hill), three kilometers (1.9 miles) from the centre of ancient Ephesus (as attested by excavations at the Seljuk castle during the 1990s). The mythical founder of the city was a prince of Athens named Androklos, who had to leave his country after the death of his father, King Kodros. According to the legend, he founded Ephesus on the place where the oracle of Delphi became reality ("A fish and a boar will show you the way"). He was a successful warrior, and as a king he was able to join the twelve cities of Ionia together into the Ionian League. During his reign the city began to prosper. He died in a battle against the Carians when he came to the aid of Priene, another city of the Ionian League.[12] Androklos and his dog are depicted on the Hadrian temple frieze, dating from the 2nd century. Later, Greek historians such as Pausanias, Strabo and Herodotos and the poet Kallinos reassigned the city's mythological foundation to Ephos, queen of the Amazons.

The Greek goddess Artemis and the great Anatolian goddess Kybele were identified together as Artemis of Ephesus. The many-breasted "Lady of Ephesus", identified with Artemis, was venerated in the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the World and the largest building of the ancient world according to Pausanias (4.31.8). Pausanias mentions that the temple was built by Ephesus, son of the river god Caystrus,[13] before the arrival of the Ionians. Of this structure, scarcely a trace remains.

Ancient sources seem to indicate that an older name of the place was Alope (Ancient Greek: Ἀλόπη, romanized: Alópē).[14]

Archaic period Street scene at the archeological excavations at Ephesus.

Street scene at the archeological excavations at Ephesus.About 650 BC, Ephesus was attacked by the Cimmerians who razed the city, including the temple of Artemis. After the Cimmerians had been driven away, the city was ruled by a series of tyrants. Following a revolt by the people, Ephesus was ruled by a council. The city prospered again under a new rule, producing a number of important historical figures such as the elegiac poet Callinus[15] and the iambic poet Hipponax, the philosopher Heraclitus, the great painter Parrhasius and later the grammarian Zenodotos and physicians Soranus and Rufus.

Electrum coin from Ephesus, 620–600 BC. Obverse: Forepart of stag. Reverse: Square incuse punch.

Electrum coin from Ephesus, 620–600 BC. Obverse: Forepart of stag. Reverse: Square incuse punch.About 560 BC, Ephesus was conquered by the Lydians under king Croesus, who, though a harsh ruler, treated the inhabitants with respect and even became the main contributor to the reconstruction of the temple of Artemis.[16] His signature has been found on the base of one of the columns of the temple (now on display in the British Museum). Croesus made the populations of the different settlements around Ephesus regroup (synoikismos) in the vicinity of the Temple of Artemis, enlarging the city.

Later in the same century, the Lydians under Croesus invaded Persia. The Ionians refused a peace offer from Cyrus the Great, siding with the Lydians instead. After the Persians defeated Croesus, the Ionians offered to make peace, but Cyrus insisted that they surrender and become part of the empire.[17] They were defeated by the Persian army commander Harpagos in 547 BC. The Persians then incorporated the Greek cities of Asia Minor into the Achaemenid Empire. Those cities were then ruled by satraps.

Ephesus has intrigued archaeologists because for the Archaic Period there is no definite location for the settlement. There are numerous sites to suggest the movement of a settlement between the Bronze Age and the Roman period, but the silting up of the natural harbours as well as the movement of the Kayster River meant that the location never remained the same.

Classical period

Ephesus continued to prosper, but when taxes were raised under Cambyses II and Darius, the Ephesians participated in the Ionian Revolt against Persian rule in the Battle of Ephesus (498 BC), an event which instigated the Greco-Persian wars. In 479 BC, the Ionians, together with Athens, were able to oust the Persians from the shores of Asia Minor. In 478 BC, the Ionian cities with Athens entered into the Delian League against the Persians. Ephesus did not contribute ships but gave financial support.

During the Peloponnesian War, Ephesus was first allied to Athens[18] but in a later phase, called the Decelean War, or the Ionian War, sided with Sparta, which also had received the support of the Persians. As a result, rule over the cities of Ionia was ceded again to Persia.

These wars did not greatly affect daily life in Ephesus. The Ephesians were surprisingly modern in their social relations:[19] they allowed strangers to integrate and education was valued. In later times, Pliny the Elder mentioned having seen at Ephesus a representation of the goddess Diana by Timarete, the daughter of a painter.[20]

In 356 BC the temple of Artemis was burnt down, according to legend, by a lunatic called Herostratus. The inhabitants of Ephesus at once set about restoring the temple and even planned a larger and grander one than the original.

Hellenistic period Historical map of Ephesus, from Meyers Konversationslexikon, 1888

Historical map of Ephesus, from Meyers Konversationslexikon, 1888When Alexander the Great defeated the Persian forces at the Battle of Granicus in 334 BC, the Greek cities of Asia Minor were liberated. The pro-Persian tyrant Syrpax and his family were stoned to death, and Alexander was greeted warmly when he entered Ephesus in triumph. When Alexander saw that the temple of Artemis was not yet finished, he proposed to finance it and have his name inscribed on the front. But the inhabitants of Ephesus demurred, claiming that it was not fitting for one god to build a temple to another. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Ephesus in 290 BC came under the rule of one of Alexander's generals, Lysimachus.

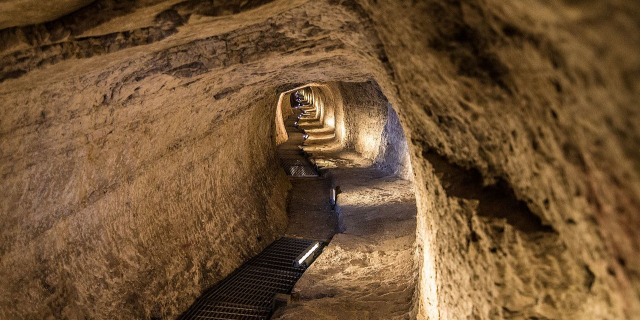

As the river Cayster (Grk. name Κάϋστρος) silted up the old harbour, the resulting marshes caused malaria and many deaths among the inhabitants. Lysimachus forced the people to move from the ancient settlement around the temple of Artemis to the present site two kilometres (1.2 miles) away, when as a last resort the king flooded the old city by blocking the sewers.[21] The new settlement was officially called Arsinoea (Ancient Greek: Ἀρσινόεια[22] or Ἀρσινοΐα[23]) or Arsinoe (Ἀρσινόη),[24][25] after the king's second wife, Arsinoe II of Egypt. After Lysimachus had destroyed the nearby cities of Lebedos and Colophon in 292 BC, he relocated their inhabitants to the new city.

Ephesus revolted after the treacherous death of Agathocles, giving the Hellenistic king of Syria and Mesopotamia Seleucus I Nicator an opportunity for removing and killing Lysimachus, his last rival, at the Battle of Corupedium in 281 BC. After the death of Lysimachus the town again was named Ephesus.

Thus Ephesus became part of the Seleucid Empire. After the murder of king Antiochus II Theos and his Egyptian wife in 246 BC, pharaoh Ptolemy III invaded the Seleucid Empire and the Egyptian fleet swept the coast of Asia Minor. Ephesus was betrayed by its governor Sophron into the hands of the Ptolemies who ruled the city for half a century until 197 BC.

The Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great tried to regain the Greek cities of Asia Minor and recaptured Ephesus in 196 BC but he then came into conflict with Rome. After a series of battles, he was defeated by Scipio Asiaticus at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC. As a result of the subsequent Treaty of Apamea, Ephesus came under the rule of Eumenes II, the Attalid king of Pergamon, (ruled 197–159 BC). When his grandson Attalus III died in 133 BC without male children of his own, he left his kingdom to the Roman Republic, on condition that the city of Pergamon be kept free and autonomous.

Classical Roman period (129 BC–395 AD) The Temple of Hadrian

The Temple of HadrianEphesus, as part of the kingdom of Pergamon, became a subject of the Roman Republic in 129 BC after the revolt of Eumenes III was suppressed.

The Theatre of Ephesus with harbour street. Due to ancient and subsequent deforestation, overgrazing (mostly by goat herds), erosion and soil degradation, the Mediterranean coast is now 3–4 km (2–2 mi) away from the site, sediment having filled the plain and the coast. In the background can be seen the muddy remains of the former harbour, barren hill ridges and maquis shrubland.

The Theatre of Ephesus with harbour street. Due to ancient and subsequent deforestation, overgrazing (mostly by goat herds), erosion and soil degradation, the Mediterranean coast is now 3–4 km (2–2 mi) away from the site, sediment having filled the plain and the coast. In the background can be seen the muddy remains of the former harbour, barren hill ridges and maquis shrubland. Stone carving of the goddess Nike

Stone carving of the goddess NikeThe city felt Roman influence at once; taxes rose considerably, and the treasures of the city were systematically plundered. Hence in 88 BC Ephesus welcomed Archelaus, a general of Mithridates, king of Pontus, when he conquered Asia (the Roman name for western Anatolia). From Ephesus, Mithridates ordered every Roman citizen in the province to be killed which led to the Asiatic Vespers, the slaughter of 80,000 Roman citizens in Asia, or any person who spoke with a Latin accent. Many had lived in Ephesus, and statues and monument of Roman citizens in Ephesus were also destroyed. But when they saw how badly the people of Chios had been treated by Zenobius, a general of Mithridates, they refused entry to his army. Zenobius was invited into the city to visit Philopoemen, the father of Monime, the favourite wife of Mithridates, and the overseer of Ephesus. As the people expected nothing good of him, they threw him into prison and murdered him. Mithridates took revenge and inflicted terrible punishments. However, the Greek cities were given freedom and several substantial rights. Ephesus became, for a short time, self-governing. When Mithridates was defeated in the First Mithridatic War by the Roman consul Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Ephesus came back under Roman rule in 86 BC. Sulla imposed a huge indemnity, along with five years of back taxes, which left Asian cities heavily in debt for a long time to come.[26]

King Ptolemy XII Auletes of Egypt retired to Ephesus in 57 BCE, passing his time in the sanctuary of the temple of Artemis when the Roman Senate failed to restore him to his throne.[27]

Mark Antony was welcomed by Ephesus for periods when he was proconsul[28] and in 33 BC with Cleopatra when he gathered his fleet of 800 ships before the battle of Actium with Octavius.[29]

When Augustus became emperor in 27 BCE, the most important change was when he made Ephesus the capital of proconsular Asia (which covered western Asia Minor) instead of Pergamum. Ephesus then entered an era of prosperity, becoming both the seat of the governor and a major centre of commerce. According to Strabo, it was second in importance and size only to Rome.[30]

The city and temple were destroyed by the Goths in 263 CE. This marked the decline of the city's splendour. However emperor Constantine the Great rebuilt much of the city and erected new public baths.

The Roman population The 'terrace houses' at Ephesus, showing how the wealthy lived during the Roman period. Eventually the harbour became silted up, and the city lost its natural resources.

The 'terrace houses' at Ephesus, showing how the wealthy lived during the Roman period. Eventually the harbour became silted up, and the city lost its natural resources.Until recently, the population of Ephesus in Roman times was estimated to number up to 225,000 people by Broughton.[31][32] More recent scholarship regards these estimates as unrealistic. Such a large estimate would require population densities seen in only a few ancient cities, or extensive settlement outside the city walls. This would have been impossible at Ephesus because of the mountain ranges, coastline and quarries which surrounded the city.[33]

The wall of Lysimachus has been estimated to enclose an area of 415 hectares (1,030 acres). Not all of this area was inhabited due to public buildings and spaces in the city center and the steep slope of the Bülbül Dağı mountain, which was enclosed by the wall. Ludwig Burchner estimated this area with the walls at 1000 acres. Jerome Murphy-O'Connor uses an estimate of 345 hectares for the inhabited land or 835 acres (Murphey cites Ludwig Burchner). He cites Josiah Russell using 832 acres and Old Jerusalem in 1918 as the yardstick estimated the population at 51,068 at 148.5 persons per hectare. Using 510 persons per hectare, he arrives at a population between 138,000 and 172,500 .[34] J.W. Hanson estimated the inhabited space to be smaller, at 224 hectares (550 acres). He argues that population densities of 150~250 people per hectare are more realistic, which gives a range of 33,600–56,000 inhabitants. Even with these much lower population estimates, Ephesus was one of the largest cities of Roman Asia Minor, ranking it as the largest city after Sardis and Alexandria Troas.[35] Hanson and Ortman (2017)[36] estimate an inhabited area to be 263 hectares and their demographic model yields an estimate of 71,587 inhabitants, with a population density of 276 inhabitants per hectare. By contrast, Rome within the walls encompassed 1,500 hectares and as over 400 built-up hectares were left outside the Aurelian Wall, whose construction was begun in 274 CE and finished in 279 CE, the total inhabited area plus public spaces inside the walls consisted of ca. 1,900 hectares. Imperial Rome had a population estimated to be between 750,000 and one million (Hanson and Ortman's (2017)[36] model yields an estimate of 923,406 inhabitants), which imply in a population density of 395 to 526 inhabitants per hectare, including public spaces.

Byzantine Roman period (395–1308)Ephesus remained the most important city of the Byzantine Empire in Asia after Constantinople in the 5th and 6th centuries.[37] Emperor Flavius Arcadius raised the level of the street between the theatre and the harbour. The basilica of St. John was built during the reign of emperor Justinian I in the 6th century.

Excavations in 2022 indicate that large parts of the city were destroyed in 614/615 by a military conflict, most likely during the Sasanian War, which initiated a drastic decline in the city's population and standard of living.[38]

The importance of the city as a commercial centre further declined as the harbour, today 5 kilometres inland, was slowly silted up by the river (today, Küçük Menderes) despite repeated dredging during the city's history.[39] The loss of its harbour caused Ephesus to lose its access to the Aegean Sea, which was important for trade. People started leaving the lowland of the city for the surrounding hills. The ruins of the temples were used as building blocks for new homes. Marble sculptures were ground to powder to make lime for plaster.

Sackings by the Arabs first in the year 654–655 by caliph Muawiyah I, and later in 700 and 716 hastened the decline further.

When the Seljuk Turks conquered Ephesus in 1090,[40] it was a small village. The Byzantines resumed control in 1097 and changed the name of the town to Hagios Theologos. They kept control of the region until 1308. Crusaders passing through were surprised that there was only a small village, called Ayasalouk, where they had expected a bustling city with a large seaport. Even the temple of Artemis was completely forgotten by the local population. The Crusaders of the Second Crusade fought the Seljuks just outside the town in December 1147.

Pre-Ottoman period (1304–1390) The İsa Bey Mosque constructed in 1374–75, is one of the oldest and most impressive remains from the Anatolian beyliks.

The İsa Bey Mosque constructed in 1374–75, is one of the oldest and most impressive remains from the Anatolian beyliks.The town surrendered, on 24 October 1304, to Sasa Bey, a Turkish warlord of the Menteşoğulları principality. Nevertheless, contrary to the terms of the surrender the Turks pillaged the church of Saint John and deported most of the local population to Thyrea, Greece when a revolt seemed probable. During these events many of the remaining inhabitants were massacred.[41]

Shortly afterwards, Ephesus was ceded to the Aydinid principality that stationed a powerful navy in the harbour of Ayasuluğ (the present-day Selçuk, next to Ephesus). Ayasoluk became an important harbour, from which piratical raids to the surrounding Christian regions were organised, both official by the state and private.[42]

The town knew again a short period of prosperity during the 14th century under these new Seljuk rulers. They added important architectural works such as the İsa Bey Mosque, caravansaries and Turkish bathhouses (hamam).

Ephesians were incorporated as vassals into the Ottoman Empire for the first time in 1390. The Central Asian warlord Tamerlane defeated the Ottomans in Anatolia in 1402, and the Ottoman sultan Bayezid I died in captivity. The region was restored to the Anatolian beyliks. After a period of unrest, the region was again incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1425.

Ephesus was completely abandoned by the 15th century. Nearby Ayasuluğ (Ayasoluk being a corrupted form of the original Greek name[43]) was turkified to Selçuk in 1914.

Gökovalı, Şadan; Altan Erguvan (1982) Ephesus, Ticaret Matbaacılık, p.7. ^ Foss, Clive (1979). Ephesus After Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ^ Foss, Clive (1979). Ephesus After Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. viii. ^ "Bruce F.F., "St John at Ephesus", The John Rylands University Library, 60 (1978), p. 339" (PDF).

Add new comment