أربيل

( Erbil )

Erbil (Arabic: أربيل, romanized: Arbīl; Syriac: ܐܲܪܒܹܝܠ, romanized: Arbel), also called Hawler (Kurdish: هەولێر, romanized: Hewlêr), is the capital and most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The city is in the Erbil Governorate.

Human settlement at Erbil may be dated back to the 5th millennium BC. At the heart of the city is the ancient Citadel of Erbil and Mudhafaria Minaret. The earliest historical reference to the region dates to the Third Dynasty of Ur of Sumer, when King Shulgi mentioned the city of Urbilum. The city was later conquered by the Assyrians.

...Read more

Erbil (Arabic: أربيل, romanized: Arbīl; Syriac: ܐܲܪܒܹܝܠ, romanized: Arbel), also called Hawler (Kurdish: هەولێر, romanized: Hewlêr), is the capital and most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The city is in the Erbil Governorate.

Human settlement at Erbil may be dated back to the 5th millennium BC. At the heart of the city is the ancient Citadel of Erbil and Mudhafaria Minaret. The earliest historical reference to the region dates to the Third Dynasty of Ur of Sumer, when King Shulgi mentioned the city of Urbilum. The city was later conquered by the Assyrians.

In the 3rd century BC, Erbil was an independent power in its area. It was conquered for a time by the Gutians. Beginning in the late 2nd century BC, it came under Assyrian control. Subsequent to this, it was part of the geopolitical province of Assyria under several empires in turn, including the Median Empire, the Achaemenid Empire (Achaemenid Assyria), Macedonian Empire, Seleucid Empire, Armenian Empire, Parthian Empire, Roman Assyria and Sasanian Empire, as well as being the capital of the tributary state of Adiabene between the mid-second century BC and early 2nd century AD. In ancient times the patron deity of the city was Ishtar of Arbela.

Following the Muslim conquest of Persia, the region no longer remained united, and during the Middle Ages, the city came to be ruled by the Seljuk and Ottoman empires.

Erbil's archaeological museum houses a large collection of pre-Islamic artifacts, particularly the art of Mesopotamia, and is a centre for archaeological projects in the area. The city was designated as the Arab Tourism Capital 2014 by the Arab Council of Tourism. In July 2014, the Citadel of Erbil was inscribed as a World Heritage Site.

In 2006 a small excavation was conducted by Karel Novacek of the University of West Bohemia.[1] Being so heavily occupied, the site has never been properly excavated. The Erbil Plain Archaeological Survey began in 2012. The survey combines satellite imagery and field work to determine the development and archaeology of the plain around Erbil. Besides Erbil the plain has a number of promising archaeological sites, most notably Tell Baqrta.[2][3] Tell Baqrta is a very large, 80 hectare, site which dates back to the Early Bronze Age.[4] In 2013 a team from the Sapienza University of Rome conducted some ground penetrating radar work on the center of the citadel. Starting in 2014 an Iraqi-led excavation began on a citadel location where the collapse of a modern building provided an opportunity for excavation. Historical aerial photographs and ground survey have also begun on the lower city.[5]

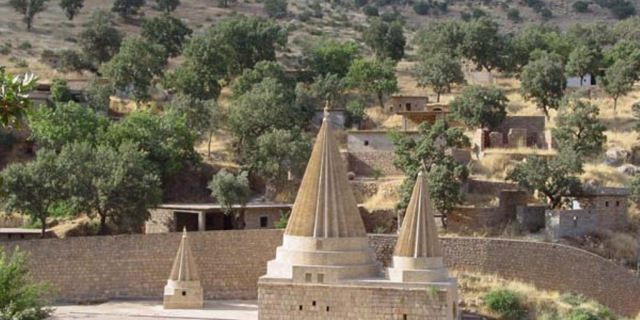

Ancient history Citadel of Erbil, declared World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2014[6]

Citadel of Erbil, declared World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2014[6] Chaldean Catholic Cathedral of Saint Joseph in Ankawa, a suburb of Erbil

Chaldean Catholic Cathedral of Saint Joseph in Ankawa, a suburb of ErbilThe region in which Erbil lies was largely under Sumerian domination from c. 3000 BC, until the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) which united all of the Akkadian Semites and Sumerians of Mesopotamia under one rule.[7]

The first mention of Erbil in literary sources comes from the archives of the kingdom of Ebla. They record two journeys to Erbil (Irbilum) by a messenger from Ebla around 2300 BFC. Erridupizir, king of the kingdom of Gutium, captured the city in 2150 BC.[8] The Neo-Sumerian ruler of Ur, Amar-Sin, sacked Urbilum in his second year, c. 1975 BC.[9]

In the centuries after the fall of the Ur III empire Erbil became a power in its area.It was conquered by Shamsi-Adad I during his short lived Upper Mesopotamian Kingdom, becoming independent after its fall. By the time of the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1050 BC) Erbil was within the Assyrian zone of control which largely extended into the Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC). The city then changed hands a number of times including the Persian, Greek, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid rule.

Under the Medes, Cyaxares might have settled a number of people from the ancient Iranian tribe of Sagartians in the Assyrian cities of Arbela and Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), probably as a reward for their help in the capture of Nineveh. According to Classical authors, the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great occupied Assyria in 547 BC and established it as an Achaemenid military protectorate state (or satrapy) called in Old Persian Aθurā (Athura), with Babylon as the capital.[10]

The Battle of Gaugamela, in which Alexander the Great defeated Darius III of Persia, took place in 331 BC approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) west of Erbil according to Urbano Monti's world map.[11] After the battle, Darius managed to flee to the city. (Somewhat inaccurately, the confrontation is sometimes known as the "Battle of Arbela".) Subsequently, Arbela was part of Alexander's Empire. After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, Arbela became part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire.

Erbil became part of the region disputed between Rome and Persia under the Sasanids. During the Parthian era to early Sassanian era, Erbil became the capital of the state of Adiabene (Assyrian Ḥadyab). The town and kingdom are known in Jewish history for the conversion of the royal family to Judaism.[12]

Its populace then gradually converted from the ancient Mesopotamian religion between the first and fourth centuries to Christianity, with Pkidha traditionally becoming its first bishop around 104 AD. The ancient Mesopotamian religion did not die out entirely in the region until the tenth century AD.[13][14] The Adiabene (East Syriac ecclesiastical province) in Arbela (Syriac: ܐܪܒܝܠ Arbel) became a centre of eastern Syriac Christianity until late in the Middle Ages.[15]

Medieval historyAs many of the Assyrians who had converted to Christianity adopted Biblical (including Jewish) names, most of the early bishops had Eastern Aramaic or Jewish/Biblical names, which does not suggest that many of the early Christians in this city were converts from Judaism.[16] It served as the seat of a Metropolitan of the Assyrian Church of the East. From the city's Christian period come many church fathers and well-known authors in Aramaic.

Following the Muslim conquest of Persia, the Sassanian province of Naxwardašīragān and later Garamig ud Nodardashiragan,[17] of which Erbil made part of, was dissolved, and from the mid-seventh century AD the region saw a gradual influx of Muslim peoples, predominantly Arabs and Turkic peoples.

The most notable Kurdish tribe in the region was the Hadhabani, of which several individuals also acted as governors for the city from the late tenth century until the 12th century when it was conquered by the Zengids and its governorship given to the Turkic Begtegenids, of whom the most notable was Gökböri, who retained the city during the Ayyubid era.[18][19] Yaqut al-Hamawi further describes Erbil as being mostly Kurdish-populated in the 13th century.[20]

Siege of Erbil by the Ilkhanid Mongols in 1258–59 depicted in the Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Division Orientale

Siege of Erbil by the Ilkhanid Mongols in 1258–59 depicted in the Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Division OrientaleWhen the Mongols invaded the Near East in the 13th century, they attacked Arbil for the first time in 1237. They plundered the lower town but had to retreat before an approaching Caliphate army and had to put off the capture of the citadel.[21][broken footnote] After the fall of Baghdad to Hülegü and the Mongols in 1258, the last Begtegenid ruler surrendered to the Mongols, claiming the Kurdish garrison of the city would follow suit; they refused this however, therefore the Mongols returned to Arbil and were able to capture the citadel after a siege lasting six months.[22][23] Hülegü then appointed a Christian Assyrian governor to the town, and the Syriac Orthodox Church was allowed to build a church.

As time passed, sustained persecutions of Christians, Jews and Buddhists throughout the Ilkhanate began in earnest in 1295 under the rule of Oïrat amir Nauruz, which affected the indigenous Christian Assyrians greatly.[24] This manifested early on in the reign of the Ilkhan Ghazan. In 1297, after Ghazan had felt strong enough to overcome Nauruz's influence, he put a stop to the persecutions.

During the reign of the Ilkhan Öljeitü, the Assyrian inhabitants retreated to the citadel to escape persecution. In the Spring of 1310, the Malek (governor) of the region attempted to seize it from them with the help of the Kurds. Despite the Turkic bishop Mar Yahballaha's best efforts to avert the impending doom, the citadel was at last taken after a siege by Ilkhanate troops and Kurdish tribesmen on 1 July 1310, and all the defenders were massacred, including many of the Assyrian inhabitants of the lower town.[25][26]

However, the city's Assyrian population remained numerically significant until the destruction of the city by the forces of Timur in 1397.[27]

In the Middle Ages, Erbil was ruled successively by the Umayyads, the Abbasids, the Buwayhids, the Seljuks and then the Turkmen Begtegīnid Emirs of Erbil (1131–1232), most notably Gökböri, one of Saladin's leading generals; they were in turn followed by the Ilkhanids, the Jalayirids, the Kara Koyunlu, the Timurids and the Ak Koyunlu. Erbil was the birthplace of the famous 12th and 13th century Kurdish historians and writers Ibn Khallikan and Ibn al-Mustawfi. After the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, Erbil came under the Soran emirate. In the 18th century Baban Emirate took the city but it was retaken by Soran ruler Mir Muhammed Kor in 1822. The Soran emirate continued ruling over Erbil until it was taken by the Ottomans in 1851. Erbil became a part of the Mosul vilayet in Ottoman Empire until World War I, when the Ottomans and their Kurdish and Turkmen allies were defeated by the British Empire.

The MedesThe Medes, and with them the Sagarthians, were to revolt against Darius I of Persia in 522 BC, but this revolt was firmly put down by the army which Darius sent out under the leadership of General Takhmaspada the following year. The events are depicted in the Behistun Inscription which stands today in the mountains of Iran's Kermanshah province. Ever the buffer zone between the two great empires of Byzantium and Persia, the plains of 10 km to the west of Erbil were to witness the Battle of Gaugemela between Alexander the Great and Darius III of Persia in 331 BC. Vanquished, Darius managed to flee to Erbil, which is why the battle is still sometimes referred to – rather inaccurately – as the Battle of Erbil.

Erbil went on to be the seat of rule of the Adiabene Kingdom in the first century AD, largely located to the northwest in the region of modern-day Diyarbakir in Turkey. It is remembered in Jewish traditions for the notable conversion of its Queen, Helena of Adiabene, to Judaism before she moved on to Jerusalem. Early Christianity was also to flourish in Erbil with a bishop established in the town as early as AD 100 with a community of followers thought to be converts from Judaism.[15]

Provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres for an independent Kurdistan (in 1920)Modern history

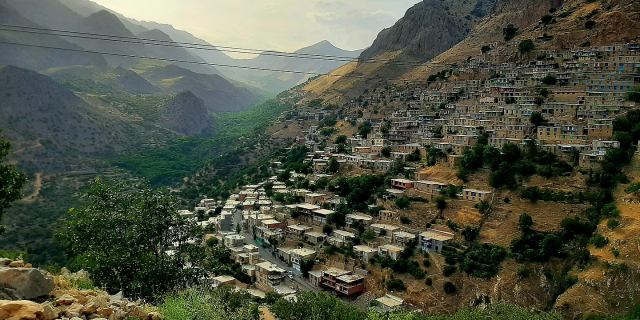

Provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres for an independent Kurdistan (in 1920)Modern historyErbil lies on the plain beneath the mountains, but for the most part, the inhabitants of Iraqi Kurdistan dwell up above in the rugged and rocky terrain that is the traditional habitat of the Kurds since time immemorial.[28]

A postcard showing the city of Erbil in 1900

A postcard showing the city of Erbil in 1900The modern town of Erbil stands on a tell topped by an Ottoman fort. During the Middle Ages, Erbil became a major trading centre on the route between Baghdad and Mosul, a role which it still plays today with important road links to the outside world.

Erbil Main Square

Erbil Main Square The patriarchate of the Assyrian Church of the East in Erbil

The patriarchate of the Assyrian Church of the East in ErbilErbil is also home to a large population of refugees due to ongoing conflicts in Syria. In 2020, it was estimated that 450,000 refugees had settled in the Erbil metropolitan area since 2003, with many of them expected to remain.[29]

The parliament of the Iraqi Kurdistan was established in Erbil in 1970 after negotiations between the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) led by Mustafa Barzani, but was effectively controlled by Saddam Hussein until the Kurdish uprising at the end of the 1991 Gulf War. The legislature ceased to function effectively in the mid-1990s when fighting broke out between the two main Kurdish factions, the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The city was captured by the KDP in 1996 with the assistance of the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein. The PUK then established an alternative Kurdish government in Sulaimaniyah. KDP claimed that in March 1996, PUK asked for Iran's help to fight KDP. Considering this as a foreign attack on Iraq's soil, the KDP asked Saddam Hussein for help.

The Kurdish Parliament in Erbil reconvened after a peace agreement was signed between the Kurdish parties in 1997, but had no real power. The Kurdish government in Erbil had control only in the western and northern parts of the autonomous region. During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, a United States special forces task force was headquartered just outside Erbil. The city was the scene of celebrations on 10 April 2003 after the fall of the Ba'ath regime.

Erbil Clock Tower

Erbil Clock TowerDuring the U.S. occupation of Iraq, sporadic attacks hit Erbil. Parallel bomb attacks against Eid celebrations killed 117 people in February 2004.[30] Responsibility was claimed by Ansar al-Sunnah.[30] A suicide bombing in May 2005 killed 60 civilians and injured 150 more outside a police recruiting centre.[31]

The Erbil International Airport opened in the city in 2005.[32]

In September 2013, a quintuple car bombing killed six people.

In 2015, the Assyrian Church of the East moved its seat from Chicago to Erbil.

In February 2021, a series of missiles hit the city killing two and injuring eight people. Further missile attacks took place in March 2022.

Add new comment