The Ica stones are a collection of andesite stones from the Ica Province in Peru, known for their engraved motifs. Largely regarded to be modern hoaxes, the stones in some cases utilize art styles from various pre-Columbian Peruvian civilizations and often depict anachronistic scenes or objects, including dinosaurs and advanced technology.

Stones with engraved artwork were first reported in Peru in the middle fifteenth century during the Spanish conquest. Subsequent archaeological finds have been next to non-existent, though huaqueros (grave robbers) at some point prior to the 1960s began selling stones similar to the Ica stones. The modern set of stones were first popularized in the 1960s and 1970s. The most widely known collection of stones, numbering around 20,000 individual objects, belonged to the physician Javier Cabrera Darquea. Cabrera purchased the majority of his stones from the farmer Basilo Uschuya and believed them to represent evidence of an ancien...Read more

The Ica stones are a collection of andesite stones from the Ica Province in Peru, known for their engraved motifs. Largely regarded to be modern hoaxes, the stones in some cases utilize art styles from various pre-Columbian Peruvian civilizations and often depict anachronistic scenes or objects, including dinosaurs and advanced technology.

Stones with engraved artwork were first reported in Peru in the middle fifteenth century during the Spanish conquest. Subsequent archaeological finds have been next to non-existent, though huaqueros (grave robbers) at some point prior to the 1960s began selling stones similar to the Ica stones. The modern set of stones were first popularized in the 1960s and 1970s. The most widely known collection of stones, numbering around 20,000 individual objects, belonged to the physician Javier Cabrera Darquea. Cabrera purchased the majority of his stones from the farmer Basilo Uschuya and believed them to represent evidence of an ancient interstellar civilization that once existed in Peru for hundreds of millions of years. Uschuya later admitted to having forged the stones he sold to Cabrera and other farmers have also admitted to making such stones.

Since the stones have never been able to be examined in an archaeological context and no other expected evidence exists of the advanced civilization supposedly depicted on them, it is unlikely that such a society existed. The dinosaurs depicted on the stones reflect outdated ideas of dinosaur life appearance common in the 1960s and depict groups not known to have lived in South America, making it unlikely that they are depictions made by people who saw living dinosaurs. Despite by and large being seen as hoaxes, the Ica stones are popular pieces of "evidence" among certain pseudoscientific communities, such as Young Earth creationists and ancient astronaut proponents.

It is possible that some of the Ica stones are genuine pre-Columbian artifacts. This possibility is mainly maintained for stones not part of Cabrera's collection and with more conventional pre-Columbian motifs.

Archaeological discoveries show evidence of Peruvian cultures going back for several thousand years. At some later stages, the whole of modern Peru was united into a single political and cultural unit, culminating in the Inca Empire, followed by the Spanish conquest. At other stages, areas such as the Ica Valley, a habitable region separated from others by desert, developed distinctive cultures of their own.[1]

Engraved stones have been known from the region since long before the Ica stones were reported. The earliest known reports of similar artifacts are records by the Jesuit missionary Padre Simón, who travelled Peru during the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in the early and middle fifteenth century.[2][3][4] Examples of these stones were reportedly sent back to Spain in 1562.[3]

Early archaeological excavations in the Ica Province in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century by scholars such as Max Uhle, Julio C. Tello, Alfred Kroeber, William Duncan Strong and John Howland Rowe did not result in any reports of the finding of engraved andesite stones.[5] Nevertheless, engraved stones which had been looted by huaqueros (grave robbers) at some point began to be offered for sale to tourists and amateur collectors.[5]

An extraordinary[6] amount of Ica stones are known today, with the total number estimated to be around 50,000[7][2]–100,000.[8]

Cabrera's collection A collection of Ica stones surrounding a portrait of Javier Cabrera Darquea

A collection of Ica stones surrounding a portrait of Javier Cabrera DarqueaThe most widely known collection of Ica stones is that of the physician Javier Cabrera Darquea (1924–2001).[4] According to Cabrera's own account, his interest in the stones was first triggered on 13 May 1966, when he was given one of the engraved stones as a birthday present by his friend Felix Llosa Romero.[2] Possessing a keen interest in Peruvian prehistory,[2] Cabrera identified the motif of the stone as a type of prehistoric fish.[2][4] Cabrera never explained what particular fish species he believed the stone to depict or why he thought it was a prehistoric one.[9][3][10]

In order to expand his collection Cabrera reached out to the brothers Carlos and Pablo Soldi, collectors of pre-Inca Peruvian artifacts. The Soldis reportedly had a large collection of similar engraved stones, according to them found in the Ocucaje region, and sold 341 of them to Cabrera.[2] The Soldis claimed to have begun collecting the engraved stones in 1961, when a large number of them were supposedly uncovered through a flood of the Ica River.[2]

Further stones were acquired by Cabrera through being purchased from the farmer Basilo Uschuya, who provided him with many thousands of them.[2][4] In addition to his own set of acquired stones, Cabrera also kept a collection of similar stones supposedly found by his father, Bolivia Cabrera, at their plantation in the 1930s.[2][4] By the late 1970s, Cabrera's collection contained over 11,000 engraved stones.[2] While serving as a medical professional (including a tenure as the chief of the University of Lima's Department of Medicine) Cabrera initially kept his collection and interest a secret.[4] By 1970 the stones and Cabrera's ideas concerning them were becoming well-known.[2]

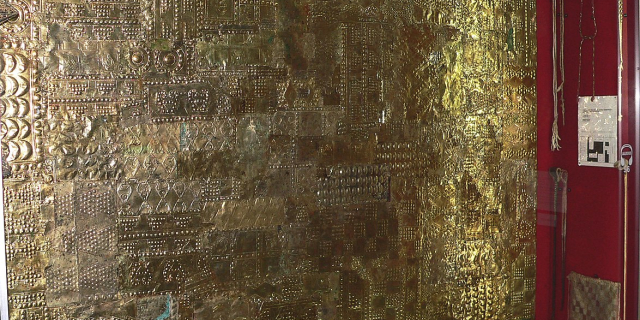

In 1996, Cabrera stopped practicing medicine and opened a museum,[4] the Museo de Piedras Grabadas ("Museum of Engraved Stones"),[3][11] to showcase his collection.[4] The museum is organized by the subject of the motif and the stones are lined up along the walls.[2] By the end of his life, Cabrera's collection reportedly contained around 20,000 stones,[3] many of which remain exhibited at his museum.[8] The National Chamber of Tourism of Peru lists the museum as a tourist destination and leaves the question of their authenticity open.[9]

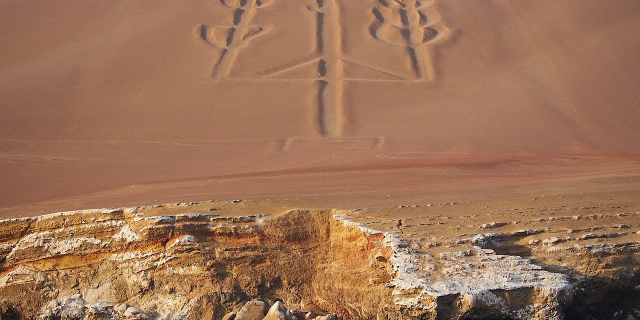

Cabrera referred to the stones as "gliptoliths" and put forth his own hypothesis on their origins, published in his book The Message of the Engraved Stones of Ica.[11] According to Cabrera, the stones were made by an ancient type of human which he called "Gliptolithic Man", who had larger brains than modern humans and could use their psychic energy to influence events in outer space. Gliptolithic Man supposedly appeared on Earth at least 405 million years ago and left the planet before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago to travel to a planet among the Pleiades.[2] The extinction event was supposedly caused by two of the Earth's three moons colliding with the planet and also resulted in the sinking of Atlantis.[12] Cabrera suggested that Gliptolithic Man left onboard electromagnetic spacecraft from the area that includes the Nazca Lines, which he thought was an "ancient spaceport".[2] Before leaving, they had supposedly been a global civilization, among other things responsible for building the pyramids of Egypt.[12] Due to a lack of evidence, Cabrera's interpretation has found little acceptance even among pseudohistorians.[2]

Calvo's collection Stone with an abstract or flower design reportedly found in 1966 by Santiago Agurto Calvo in a Paracas culture tomb

Stone with an abstract or flower design reportedly found in 1966 by Santiago Agurto Calvo in a Paracas culture tombIca stones were also collected by the architect Santiago Agurto Calvo,[4][5] rector of the National University of Engineering in Lima.[5] In addition to reportedly purchasing many such stones from locals,[4] Calvo organized searches in ancient cemeteries and in August 1966 reported the finding of an engraved stone in the Toma Luz sector, Callango district, in Ica Valley. The context of the find reportedly corresponded to the Tiwanaku culture.[5] Calvo believed that the engraved stones were part of some ancient burial ritual.[4]

Calvo reported his discovery to the Regional Museum of Ica, and was accompanied on further expeditions by its curator, the archaeologist Alejandro Pezzia Assereto.[5] In September 1966 in Uhle Hill cemetery, De la Banda sector, Ocucaje District, they reportedly found an engraved stone in a tomb of the Paracas culture. On the small stone, a few centimetres across, was engraved a design which might be abstract, or could be taken as a flower with eight petals.[5] Calvo published the discovery in a Lima newspaper.[13] Pezzia continued to search. In the San Evaristo cemetery in Toma Luz, he reported the find of an engraved stone of similar size to the previous one, depicting a fish. The context reportedly dated the tomb to the Middle Horizon (c. 600–1000 A.D.). In a nearby grave in the same cemetery, Pezzia reported the find of a stone depicting a llama. Pezzia published his findings in 1968, including drawings and descriptions.[5]

In 1968, Calvo donated some of the stones of his collection to the Regional Museum of Ica, and also unsuccessfully sought to have the region where they had been found made into a special preserve so that ancient objects could not be removed illegally.[2] The stones were exhibited at the museum, labelled as "pre-Inca burial art",[4] until they were removed in 1970[2] once Cabrera's collection and ideas concerning similar stones began to be publicized, the museum now believing them to be hoaxes.[4]

Add new comment