Madurai ( MUH-doo-rai, US also MAH-də-RY, Tamil: [mɐðuɾɐi̯]) is a major city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the cultural capital of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Madurai District. As of the 2011 census, it was the third largest urban agglomeration in Tamil Nadu after Chennai and Coimbatore and the 33rd most populated city in India. Located on the banks of River Vaigai, Madurai has been a major settlement for two millennia and has a documented history of more than 2500 years. It is often referred to as "Thoonga Nagaram", meaning "the city that never sleeps".

Madurai is closely associated with the Tamil language. The third Tamil Sangam, a major congregation of Tamil scholars, is said to hav...Read more

Madurai ( MUH-doo-rai, US also MAH-də-RY, Tamil: [mɐðuɾɐi̯]) is a major city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the cultural capital of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Madurai District. As of the 2011 census, it was the third largest urban agglomeration in Tamil Nadu after Chennai and Coimbatore and the 33rd most populated city in India. Located on the banks of River Vaigai, Madurai has been a major settlement for two millennia and has a documented history of more than 2500 years. It is often referred to as "Thoonga Nagaram", meaning "the city that never sleeps".

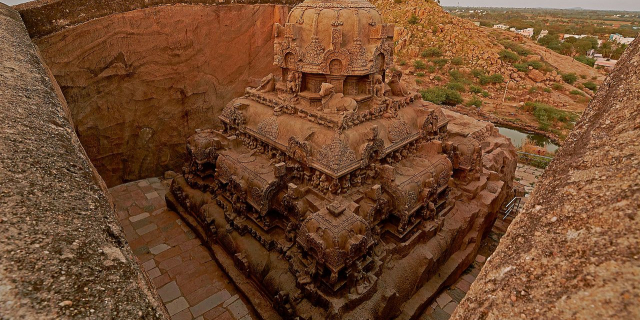

Madurai is closely associated with the Tamil language. The third Tamil Sangam, a major congregation of Tamil scholars, is said to have been held in the city. The recorded history of the city goes back to the 3rd century BCE, being mentioned by Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Mauryan Empire, and Kautilya, a minister of the Mauryan emperor Chandragupta Maurya. Signs of human settlements and Roman trade links dating back to 300 BCE are evident from excavations by Archeological Survey of India in Manalur. The city is believed to be of significant antiquity and has been ruled, at different times, by the Pandyas, Cholas, Madurai Sultanate, Vijayanagar Empire, Madurai Nayaks, Carnatic kingdom, and the British East India Company British Raj. The city has a number of historical monuments, with the Koodal Azhagar temple, Meenakshi Temple and the Thirumalai Nayakkar Mahal being the most prominent.

Madurai is an important industrial and educational hub in South Tamil Nadu. The city is home to various automobile, rubber, chemical and granite manufacturing industries. Madurai has important government educational institutes such as the Madurai Medical College, Homeopathic Medical College, Madurai Law College, Agricultural College and Research Institute. Madurai city is administered by a municipal corporation established in 1971 as per the Municipal Corporation Act. The city covers an area of 147.97 km2 (57.13 sq mi) and had a population of 1,470,755 in 2011. The city is also the seat of a bench of the Madras High Court.

It is one of the few towns and cities in List of AMRUT Smart cities in Tamil Nadu selected for AMRUT Schemes from central government and the developmental activities are taken care by government of Tamil Nadu.

Hand coloured antique wood engraving drawn by W. Purser (1858) shows Madurai city and Meenakshi Temple as seen from the north bank of the Vaigai river

Hand coloured antique wood engraving drawn by W. Purser (1858) shows Madurai city and Meenakshi Temple as seen from the north bank of the Vaigai riverMadurai is mentioned in the Buddhist text Mahavamsa, that in the 6th century BCE, Prince Vijaya (BCE 543–505) married the daughter of King Pandu of Madurai and 700 men of prince Vijaya married 700 maidens from Madurai as their wives. The princess and maidens were sent to Sri Lanka with valuable items by ships and they landed in MahaTittha, present-day Mannar.[1]

Madurai has been inhabited since at least the 3rd century BCE.[2] Megasthenes may have visited Madurai during the 3rd century BCE, with the city referred as "Methora" in his accounts.[3] The view is contested by some scholars who believe "Methora" refers to the north Indian city of Mathura, as it was a large and established city in the Mauryan Empire.[4] Madurai is also mentioned in Kautilya's (370–283 BCE)[5] Arthashastra.[3] Sangam literature like Maturaikkāñci records the importance of Madurai as a capital city of the Pandyan dynasty.[6][7] Madurai is mentioned in the works of Roman historians Pliny the Younger (61 – c. 112 CE), Ptolemy (c. 90 – c. CE 168), those of the Greek geographer Strabo (64/63 BCE – c. 24 CE),[8] and also in Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.[9]

Pandyan dynasty at its greatest extent

Pandyan dynasty at its greatest extent Coin of Jalaluddin Ahsan Khan, first ruler of the Sultanate of Madurai, 1335–1339 CE

Coin of Jalaluddin Ahsan Khan, first ruler of the Sultanate of Madurai, 1335–1339 CEAfter the Sangam age, most of present-day Tamil Nadu, including Madurai, came under the rule of the Kalabhra dynasty,[10] which was ousted by the Pandyas around 590 CE.[11][12] The Pandyas were ousted from Madurai by the Chola dynasty during the early 9th century. The city was fought over between the Cholas and the Pandyas during the 12th century, changing hands several times,[13] until the early 13th century, when the second Pandyan empire was established with Madurai as its capital.[14] After the death of Kulasekara Pandian (1268–1308 CE), Madurai came under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate.[14] The Madurai Sultanate then seceded from Delhi and functioned as an independent kingdom until its gradual annexation by the Vijayanagara Empire in 1378 CE. Madurai became independent from Vijayanagar in 1559 CE under the Nayaks.[15] Nayak rule ended in 1736 CE and Madurai was repeatedly captured several times by Chanda Sahib (1740 – 1754 CE), Arcot Nawab and Muhammed Yusuf Khan (1725 – 1764 CE) in the middle of the 18th century.[3]

In 1801, Madurai came under the direct control of the British East India Company and was annexed to the Madras Presidency.[16][17] The British government made donations to the Meenakshi temple and participated in the Hindu festivals during the early part of their rule. The city evolved as a political and industrial complex through the 19th and 20th centuries to become a district headquarters of a larger Madurai district.[18] In 1837, the fortifications around the temple were demolished by the British.[19] The moat was drained and the debris was used to construct new streets – Veli, Marat and Perumaal Mesthiri streets.[20] The city was constituted as a municipality in 1866 under the Town Improvement Act of 1865.[21] The British government faced initial hiccups during the earlier period of the establishment of municipality in land ceiling and tax collection in Madurai and Dindigul districts under the direct administration of the officers of the government. The city, along with the district, was resurveyed between 1880 and 1885 CE and subsequently, five municipalities were constituted in the two districts and six taluk boards were set up for local administration. Police stations were established in Madurai city, housing the headquarters of the District Superintendent.[22]

It was in Madurai, in 1921, that Mahatma Gandhi, pre-eminent leader of Indian nationalism in British-ruled India, first adopted the loin cloth as his mode of dress after seeing agricultural labourers wearing it.[23] Leaders of the independence movement in Madurai included N. M. R. Subbaraman,[24][25] Karumuttu Thiagarajan Chettiar and Mohammad Ismail Sahib.[26] The Temple Entry Authorization and Indemnity Act passed by the government of Madras Presidency under C. Rajagopalachari in 1939 removed restrictions prohibiting Shanars and Dalits from entering Hindu temples. The temple entry movement was first led in Madurai Meenakshi temple by independence activist A. Vaidyanatha Iyer in 1939.[27][28]

In 1971, the municipality of Madurai was upgraded to a Municipal Corporation.[29] In 2011 the Corporation of Madurai expanded the area of its jurisdiction from seventy-two wards to one hundred wards, an increase in area from 51.82 square kilometres (12,810 acres) to 147.997 square kilometres (36,571 acres).[29]

Add new comment