مقبرة 62

( Tomb of Tutankhamun )

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1332–1323 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed ...Read more

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1332–1323 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BC).

Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered in 1922 by excavators led by Howard Carter. As a result of the quantity and spectacular appearance of the burial goods, the tomb attracted a media frenzy and became the most famous find in the history of Egyptology. The death of Carter's patron, the Earl of Carnarvon, in the midst of the excavation process inspired speculation that the tomb was cursed. The discovery produced only limited evidence about the history of Tutankhamun's reign and the Amarna Period that preceded it, but it provided insight into the material culture of wealthy ancient Egyptians as well as patterns of ancient tomb robbery. Tutankhamun became one of the best-known pharaohs, and some artefacts from his tomb, such as his golden funerary mask, are among the best-known artworks from ancient Egypt.

Most of the tomb's goods were sent to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and are now in the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, although Tutankhamun's mummy and sarcophagus are still on display in the tomb. Flooding and heavy tourist traffic have inflicted damage on the tomb since its discovery, and a replica of the burial chamber has been constructed nearby to reduce tourist pressure on the original tomb.

Tutankhamun reigned as pharaoh between c. 1334 and 1325 BC, towards the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom.[1][2] He took the throne as a child after the death of Akhenaten (who was probably his father) and the subsequent brief reigns of Neferneferuaten and Smenkhkare. Akhenaten had radically reshaped ancient Egyptian religion by worshipping a single deity, Aten, and rejecting other deities, a shift that began the Amarna Period.[3] One of Tutankhamun's major acts was the restoration of traditional religious practice. His name was changed from Tutankhaten, referring to Akhenaten's deity, to Tutankhamun, honouring Amun, one of the foremost deities of the traditional pantheon. Similarly, his queen's name was changed from Ankhesenpaaten to Ankhesenamun.[4]

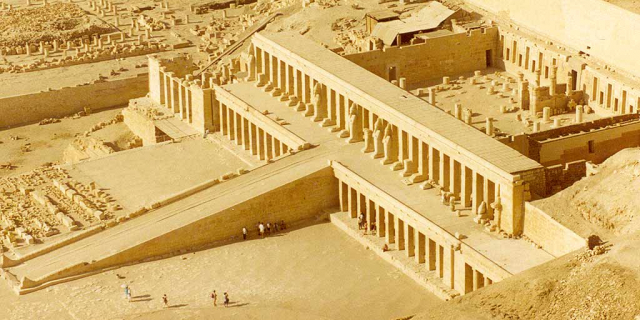

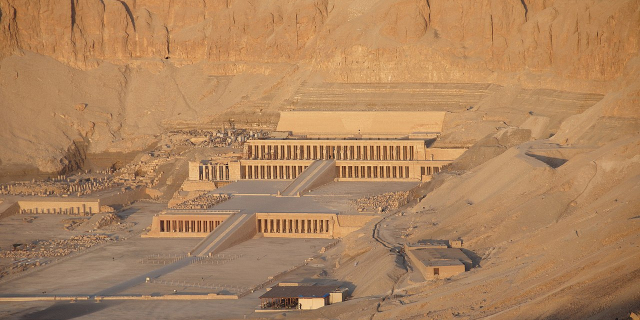

The central portion of the Valley of the Kings in 2012, with tomb entrances labeled. The covered entrance to KV62 is at centre right.

The central portion of the Valley of the Kings in 2012, with tomb entrances labeled. The covered entrance to KV62 is at centre right.Shortly after he took power, he commissioned a full-size royal tomb, which was probably one of two tombs from the same era, WV23 or KV57.[5] KV62 is thought to have originally been a non-royal tomb, possibly intended for Ay, Tutankhamun's advisor. After he died prematurely, KV62 was enlarged to accommodate his burial. Ay became pharaoh on Tutankhamun's death and was buried in WV23. Ay was elderly when he came to the throne, and it is possible that he buried Tutankhamun in KV62 in order to usurp WV23 for himself and ensure that he would have a tomb of suitably royal proportions ready when he himself died. Pharaohs in Tutankhamun's time also built mortuary temples where they would receive offerings to sustain their spirits in the afterlife. The Temple of Ay and Horemheb at Medinet Habu contained statues that were originally carved for Tutankhamun, suggesting either that Tutankhamun's temple stood nearby or that Ay usurped Tutankhamun's temple as his own.[6]

Ay was succeeded by Tutankhamun's general Horemheb, although the transfer of power may have been contested and created a brief period of political instability.[7][8] As part of the continued reaction against Atenism, Horemheb tried to erase Akhenaten and his successors from the record, dismantling Akhenaten's monuments and usurping those erected by Tutankhamun. Future king-lists skipped straight from Akhenaten's father, Amenhotep III, to Horemheb.[7]

Within a few years of Tutankhamun's burial, his tomb was robbed twice. After the first robbery, officials responsible for its security repaired and repacked some of the damaged goods before filling the outer corridor with chips of limestone, along with objects dropped by the thieves, to deter future thefts. Nevertheless, a second set of robbers burrowed through the corridor fill. This robbery too was detected, and after a second hasty restoration the tomb was once again sealed.[9]

The Valley of the Kings is subject to periodic flash floods that deposit alluvium.[10] Much of the valley, including the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb, was covered by a layer of alluvium over which huts were later built for the tomb workers who cut KV57, in which Horemheb was buried. The geologist Stephen Cross has argued that a major flood deposited this layer after KV62 was last sealed and before the huts were built, which would mean Tutankhamun's tomb had been rendered inaccessible by the time Ay's reign ended.[11] However, the Egyptologist Andreas Dorn suggests that this layer already existed during Tutankhamun's reign, and workers dug through it to reach the bedrock into which they cut his tomb.[12]

More than 150 years after Tutankhamun's burial, KV9, the tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI, was cut into the rock to the west of his tomb.[13] The entrance of his tomb was further buried by mounds of debris from KV9's excavation and by the workers' huts atop that debris. In subsequent years the tombs in the valley suffered major waves of robbery: first during the late Twentieth Dynasty by local gangs of thieves, then during the Twenty-first Dynasty by officials working for the High Priests of Amun, who stripped the tombs of their valuables and removed the royal mummies. Tutankhamun's tomb, buried and forgotten, remained undisturbed.[14]

Discovery and clearanceSeveral tombs in the Valley of the Kings lay open continuously from ancient times onward, but the entrances to many others remained hidden until after the emergence of Egyptology in the early nineteenth century.[15] Many of the remaining tombs were found by a series of excavators working for Theodore M. Davis from 1902 to 1914. Under Davis most of the valley was explored, although he never found Tutankhamun's tomb because he thought no tomb would have been cut into the valley floor.[16] Among his discoveries was KV54, a pit containing objects bearing Tutankhamun's name; these objects are now thought to have been either burial goods that were originally stored in the corridor of Tutankhamun's tomb, which were removed and reburied in KV54 when the restorers filled the corridor, or objects related to Tutankhamun's funeral. Davis's excavators also discovered a small tomb called KV58 that contained pieces of a chariot harness bearing the names of Tutankhamun and Ay. Davis was convinced that KV58 was Tutankhamun's tomb.[17]

The northwest corner of the antechamber, as photographed in 1922. The plaster partition between the antechamber and burial chamber is on the right.

The northwest corner of the antechamber, as photographed in 1922. The plaster partition between the antechamber and burial chamber is on the right.After Davis gave up work on the valley, the archaeologist Howard Carter and his patron George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, made an effort to clear the valley of debris down to the bedrock. Davis's finds of artefacts bearing Tutankhamun's name gave them reason to hope they might find his tomb.[18] The discovery began on 4 November 1922 with a single step at the top of the entrance staircase.[19] When the excavators reached the antechamber, on 26 November, it exceeded all expectations, providing unprecedented insight into what a New Kingdom royal burial was like.[20]

Workmen move goods from the tomb along a Decauville railroad track to the Nile.

Workmen move goods from the tomb along a Decauville railroad track to the Nile.The condition of the burial goods varied greatly; many had been profoundly affected by moisture, which probably derived from both the damp state of the plaster when the tomb was first sealed and from water seepage over the millennia until it was excavated.[21] Recording the tomb's contents and conserving them so they could survive to be transported to Cairo proved to be an unprecedented task, lasting for ten digging seasons.[22][23] Although many others participated, the only members of the excavation team who worked throughout the process were Carter, Alfred Lucas (a chemist who was instrumental in the conservation effort), Harry Burton (who photographed the tomb and its artefacts) and four foremen: Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said.[24]

The spectacular nature of the tomb goods inspired a media frenzy, dubbed "Tutmania", that made Tutankhamun into one of the most famous pharaohs, often known by the nickname "King Tut".[25][26] In the Western world the publicity inspired a fad for ancient Egyptian-inspired design motifs.[27] In Egypt it reinforced the ideology of pharaonism, which emphasized modern Egypt's connection to its ancient past and had risen to prominence during Egypt's struggle for independence from British rule from 1919 to 1922.[28] The publicity increased when Carnarvon died of an infection in April 1923, inspiring rumours that he had been killed by a curse on the tomb. Other deaths or strange events connected with the tomb came to be attributed to the curse as well.[29]

After Carnarvon's death, the tomb clearance continued under Carter's leadership. In the second season of the process, in late 1923 and early 1924, the antechamber was emptied of artefacts and work began on the burial chamber.[30] The Egyptian government, which had become partially independent in 1922, fought with Carter over the question of access to the tomb; the government felt that Egyptians, and especially the Egyptian press, were given too little access. In protest of the government's increasing restrictions, Carter and his associates stopped work in February 1924, beginning a legal dispute that lasted until January 1925. Under the agreement that resolved the dispute, the artefacts from the tomb would not be divided between the government and the dig's sponsors, as had been standard practice on previous Egyptological digs.[31] Instead most of the tomb's contents went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[32]

The excavators opened and removed Tutankhamun's coffins and mummy in 1925, then spent the next few seasons working on the treasury and annexe. The clearance of the tomb itself was completed in November 1930, though Carter and Lucas continued to work on conserving the remaining burial goods until February 1932, when the last shipment was sent to Cairo.[33]

Tourism and preservation The sign outside of the entrance to tomb of Tutankhamun in Arabic and English.

The sign outside of the entrance to tomb of Tutankhamun in Arabic and English.The tomb has been a popular tourist destination ever since the clearance process began.[34] Sometime after the mummy was reinterred in 1926, someone broke into the sarcophagus, stealing objects Carter had left in place. A likely time for the event is the Second World War, when a shortage of security workers led to widespread looting of Egyptian antiquities. The body was subsequently rewrapped, suggesting local officials may have discovered the break-in and restored the mummy without reporting what had happened. The theft was not exposed until 1968, after the anatomist Ronald Harrison re-examined Tutankhamun's remains.[35]

Most tombs in the Valley of the Kings tombs are vulnerable to flash flooding.[36] When analysing Tutankhamun's tomb in 1927, Lucas concluded that despite the moisture seepage, no significant liquid water had entered before its discovery.[37] In contrast, since the discovery water has periodically trickled in through the entrance, and on New Year's Day in 1991 a rainstorm flooded the tomb through a fault in the burial chamber ceiling. The flood stained the painted chamber wall and left about 7 centimetres (2.8 in) of standing water on the floor.[38] Tombs are also threatened by the tourists who visit them, who may damage the wall decoration with their touch and with the moisture introduced by their breath.[36] The mummy is also vulnerable to this kind of damage, so in 2007 it was moved to a climate-controlled glass display case that was placed in the antechamber, allowing it to be displayed to the public while protecting it from humidity and mould.[39]

The Society of Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt suggested the idea of creating a replica of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1988, so that tourists could see it without further damaging the original.[40] In 2009, Factum Arte, a workshop that specialises in replicas of large-scale artworks, took detailed scans of the burial chamber on which to base a replica,[40] while the Egyptian government and the Getty Conservation Institute launched a long-term project to assess the condition of the tomb and renovate it as needed.[41] The replica was completed in 2012 and opened to the public in 2014;[40] the renovation was completed in 2019.[42]

In 2015, the Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves argued, based on Factum Arte's scans, that the west and north walls of the burial chamber included previously unnoticed plaster partitions. That would suggest the tomb contained two previously unknown chambers, one behind each partition, which Reeves suggested were the burial place of Neferneferuaten. The Ministry of Antiquities commissioned a ground-penetrating radar examination later that year, which seemed to show voids behind the chamber walls, but follow-up radar examinations in 2016 and 2018 determined that there are no such voids and therefore no hidden chambers.[43]

Tutankhamun's tomb is in higher demand from tourists than any other in the Valley of the Kings. Up to 1,000 people pass through it on its busiest days.[44]

Add new comment