अजंता गुफाएँ

( Ajanta Caves )

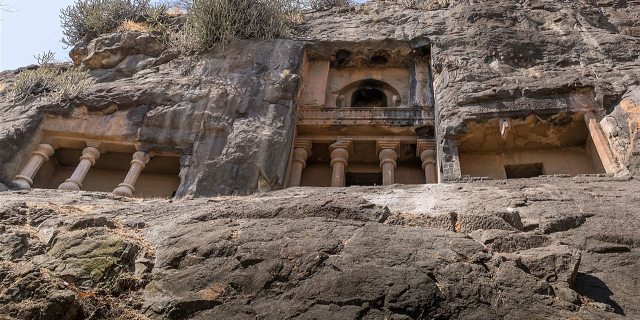

The Ajanta Caves are 29 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments dating from the second century BCE to about 480 CE in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state in India. Ajanta Caves are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Universally regarded as masterpieces of Buddhist religious art, the caves include paintings and rock-cut sculptures described as among the finest surviving examples of ancient Indian art, particularly expressive paintings that present emotions through gesture, pose and form.

The caves were built in two phases, the first starting around the second century BCE and the second occurring from 400 to 650 CE, according to older accounts, or in a brief period of 460–480 CE according to later scholarship.

The Ajanta Caves constitute ancient monasteries (Viharas) and worship-halls (Chaityas) of different Buddhist traditions carved into a 75-metre (246 ft) wall of rock. The caves also present paintings depicting the past lives and re...Read more

The Ajanta Caves are 29 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments dating from the second century BCE to about 480 CE in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state in India. Ajanta Caves are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Universally regarded as masterpieces of Buddhist religious art, the caves include paintings and rock-cut sculptures described as among the finest surviving examples of ancient Indian art, particularly expressive paintings that present emotions through gesture, pose and form.

The caves were built in two phases, the first starting around the second century BCE and the second occurring from 400 to 650 CE, according to older accounts, or in a brief period of 460–480 CE according to later scholarship.

The Ajanta Caves constitute ancient monasteries (Viharas) and worship-halls (Chaityas) of different Buddhist traditions carved into a 75-metre (246 ft) wall of rock. The caves also present paintings depicting the past lives and rebirths of the Buddha, pictorial tales from Aryasura's Jatakamala, and rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities. Textual records suggest that these caves served as a monsoon retreat for monks, as well as a resting site for merchants and pilgrims in ancient India. While vivid colours and mural wall paintings were abundant in Indian history as evidenced by historical records, Caves 1, 2, 16 and 17 of Ajanta form the largest corpus of surviving ancient Indian wall-paintings.

The Ajanta Caves are mentioned in the memoirs of several medieval-era Chinese Buddhist travellers. They were covered by jungle until accidentally "discovered" and brought to Western attention in 1819 by a colonial British officer Captain John Smith on a tiger-hunting party. The caves are in the rocky northern wall of the U-shaped gorge of the river Waghur, in the Deccan plateau. Within the gorge are a number of waterfalls, audible from outside the caves when the river is high.

With the Ellora Caves, Ajanta is one of the major tourist attractions of Maharashtra. It is about 59 kilometres (37 miles) from the city of Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India, 104 kilometres (65 miles) from the city of Aurangabad, and 350 kilometres (220 miles) east-northeast of Mumbai. Ajanta is 100 kilometres (62 miles) from the Ellora Caves, which contain Hindu, Jain and Buddhist caves, the last dating from a period similar to Ajanta. The Ajanta style is also found in the Ellora Caves and other sites such as the Elephanta Caves, Aurangabad Caves, Shivleni Caves and the cave temples of Karnataka.

Map of Ajanta Caves

Map of Ajanta CavesThe Ajanta Caves are generally agreed to have been made in two distinct phases; first during the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE, and second several centuries later.[1][2][3]

The caves consist of 36 identifiable foundations,[4] some of them discovered after the original numbering of the caves from 1 through 29. The later-identified caves have been suffixed with the letters of the alphabet, such as 15A, identified between originally numbered caves 15 and 16.[5] The cave numbering is a convention of convenience and does not reflect the chronological order of their construction.[6]

Caves of the first (Satavahana) period Cave 9, a first-period Hinayana-style chaitya worship hall with stupa but no idols

Cave 9, a first-period Hinayana-style chaitya worship hall with stupa but no idolsThe earliest group consists of caves 9, 10, 12, 13 and 15A. The murals in these caves depict stories from the Jatakas.[6] Later caves reflect the artistic influence of the Gupta period,[6] but there are differing opinions on which century in which the early caves were built.[7][8] According to Walter Spink, they were made during the period 100 BCE to 100 CE, probably under the patronage of the Hindu Satavahana dynasty (230 BCE – c. 220 CE) who ruled the region.[9][10] Other datings prefer the period of the Maurya Empire (300 BCE to 100 BCE).[11] Of these, caves 9 and 10 are stupa containing worship halls of chaitya-griha form, and caves 12, 13, and 15A are vihāras (see the architecture section below for descriptions of these types).[5] The first Satavahana period caves lacked figurative sculpture, emphasizing the stupa instead.

According to Spink, once the Satavahana period caves were made, the site was not further developed for a considerable period until the mid-5th century.[12] However, the early caves were in use during this dormant period, and Buddhist pilgrims visited the site, according to the records left by Chinese pilgrim Faxian around 400 CE.[5]

Caves of the later or Vākāṭaka periodThe second phase of construction at the Ajanta Caves site began in the 5th century. For a long time it was thought that the later caves were made over an extended period from the 4th to the 7th centuries CE,[13] but in recent decades a series of studies by the leading expert on the caves, Walter M. Spink, have argued that most of the work took place over the very brief period from 460 to 480 CE,[12] during the reign of Hindu Emperor Harishena of the Vākāṭaka dynasty.[14][15][16] This view has been criticised by some scholars,[17] but is now broadly accepted by most authors of general books on Indian art, for example, Huntington and Harle.

The second phase is attributed to the theistic Mahāyāna,[6] or Greater Vehicle tradition of Buddhism.[19][20] Caves of the second period are 1–8, 11, 14–29, some possibly extensions of earlier caves. Caves 19, 26, and 29 are chaitya-grihas, the rest viharas. The most elaborate caves were produced in this period, which included some refurbishing and repainting of the early caves.[21][6][22]

Spink states that it is possible to establish dating for this period with a very high level of precision; a fuller account of his chronology is given below.[23] Although debate continues, Spink's ideas are increasingly widely accepted, at least in their broad conclusions. The Archaeological Survey of India website still presents the traditional dating: "The second phase of paintings started around 5th–6th centuries A.D. and continued for the next two centuries".

According to Spink, the construction activity at the incomplete Ajanta Caves was abandoned by wealthy patrons in about 480 CE, a few years after the death of Harishena. However, states Spink, the caves appear to have been in use for a period of time as evidenced by the wear of the pivot holes in caves constructed close to 480 CE.[24] The second phase of constructions and decorations at Ajanta corresponds to the very apogee of Classical India, or India's golden age.[25] However, at that time, the Gupta Empire was already weakening from internal political issues and from the assaults of the Hūṇas, so that the Vakatakas were actually one of the most powerful empires in India.[26] Some of the Hūṇas, the Alchon Huns of Toramana, were precisely ruling the neighbouring area of Malwa, at the doorstep of the Western Deccan, at the time the Ajanta caves were made.[27] Through their control of vast areas of northwestern India, the Huns may actually have acted as a cultural bridge between the area of Gandhara and the Western Deccan, at the time when the Ajanta or Pitalkhora caves were being decorated with some designs of Gandharan inspiration, such as Buddhas dressed in robes with abundant folds.[28]

According to Richard Cohen, a description of the caves by 7th-century Chinese traveler Xuanzang and scattered medieval graffiti suggest that the Ajanta Caves were known and probably in use subsequently, but without a stable or steady Buddhist community presence.[29] The Ajanta caves are mentioned in the 17th-century text Ain-i-Akbari by Abu al-Fazl, as twenty four rock-cut cave temples each with remarkable idols.[29]

Colonial eraOn 28 April 1819 a British officer named John Smith, of the 28th Cavalry, while hunting tigers was shown the entrance to Cave No. 10 when a local shepherd boy guided him to the location and the door. The caves were well known by locals already.[30] Captain Smith went to a nearby village and asked the villagers to come to the site with axes, spears, torches, and drums, to cut down the tangled jungle growth that made entering the cave difficult.[30] He then deliberately damaged an image on the wall by scratching his name and the date over the painting of a bodhisattva. Since he stood on a five-foot high pile of rubble collected over the years, the inscription is well above the eye-level gaze of an adult today.[31] A paper on the caves by William Erskine was read to the Bombay Literary Society in 1822.[32]

Name and date inscribed by John Smith after he found Cave 10 in 1819

Name and date inscribed by John Smith after he found Cave 10 in 1819Within a few decades, the caves became famous for their exotic setting, impressive architecture, and above all their exceptional and unique paintings. A number of large projects to copy the paintings were made in the century after rediscovery. In 1848, the Royal Asiatic Society established the "Bombay Cave Temple Commission" to clear, tidy and record the most important rock-cut sites in the Bombay Presidency, with John Wilson as president. In 1861 this became the nucleus of the new Archaeological Survey of India.[33]

During the colonial era, the Ajanta site was in the territory of the princely state of the Hyderabad and not British India.[34] In the early 1920s, Mir Osman Ali Khan the last Nizam of Hyderabad appointed people to restore the artwork, converted the site into a museum and built a road to bring tourists to the site for a fee. These efforts resulted in early mismanagement, states Richard Cohen, and hastened the deterioration of the site. Post-independence, the state government of Maharashtra built arrival, transport, facilities, and better site management. The modern Visitor Center has good parking facilities and public conveniences and ASI operated buses run at regular intervals from Visitor Center to the caves.[34]

The Nizam's Director of Archaeology obtained the services of two experts from Italy, Professor Lorenzo Cecconi, assisted by Count Orsini, to restore the paintings in the caves.[35] The Director of Archaeology for the last Nizam of Hyderabad said of the work of Cecconi and Orsini:

The repairs to the caves and the cleaning and conservation of the frescoes have been carried out on such sound principles and in such a scientific manner that these matchless monuments have found a fresh lease of life for at least a couple of centuries.[36]

Despite these efforts, later neglect led to the paintings degrading in quality once again.[36]

Since 1983, Ajanta caves have been listed among the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of India. The Ajanta Caves, along with the Ellora Caves, have become the most popular tourist destination in Maharashtra, and are often crowded at holiday times, increasing the threat to the caves, especially the paintings.[37] In 2012, the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation announced plans to add to the ASI visitor centre at the entrance complete replicas of caves 1, 2, 16 & 17 to reduce crowding in the originals, and enable visitors to receive a better visual idea of the paintings, which are dimly-lit and hard to read in the caves.[38]

Add new comment