Sudan

Context of Sudan

Sudan (English: or ; Arabic: السودان, romanized: as-Sūdān, pronounced [suː.dæːn]), officially the Republic of the Sudan (Arabic: جمهورية السودان, romanized: Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It is bordered with the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Egypt to the north, Eritrea to the northeast, Ethiopia to the southeast, Libya to the northwest, South Sudan to the south and the Red Sea. It has a population of 45.7 mi...Read more

Sudan (English: or ; Arabic: السودان, romanized: as-Sūdān, pronounced [suː.dæːn]), officially the Republic of the Sudan (Arabic: جمهورية السودان, romanized: Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It is bordered with the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Egypt to the north, Eritrea to the northeast, Ethiopia to the southeast, Libya to the northwest, South Sudan to the south and the Red Sea. It has a population of 45.7 million people as of 2022 and occupies 1,886,068 square kilometres (728,215 square miles), making it Africa's third-largest country by area, and the third-largest by area in the Arab League. It was the largest country by area in Africa and the Arab League until the secession of South Sudan in 2011, since which both titles have been held by Algeria. Its capital city is Khartoum and its most populous city is Omdurman (part of the metropolitan area of Khartoum).

Sudan's history goes back to the pharaonic period, witnessing the Kingdom of Kerma (c. 2500–1500 BC), the subsequent rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom (c. 1500 BC–1070 BC) and the rise of the Kingdom of Kush (c. 785 BC–350 AD), which would in turn control Egypt itself for nearly a century. After the fall of Kush, the Nubians formed the three Christian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia, with the latter two lasting until around 1500. Between the 14th and 15th centuries, most of Sudan was gradually settled by Arab nomads. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, central and eastern Sudan were dominated by the Funj sultanate, while Darfur ruled the west and the Ottomans the east.

During the Mamluk and Ottoman periods, slave trade played a big role and was demanded from the Sudanese Kashif as the regular remittance of tribute. In 1811, Mamluks established a state at Dunqulah as a base for their slave trading. Under Turco-Egyptian rule of Sudan after the 1820s, the practice of trading slaves was entrenched along a north–south axis, with slave raids taking place in southern parts of the country and slaves being transported to Egypt and the Ottoman empire.

From the early 19th century, the entirety of Sudan was conquered by the Egyptians under the Muhammad Ali dynasty. It was under Egyptian rule that Sudan acquired its modern borders and began the process of political, agricultural, and economic development. In 1881, nationalist sentiment in Egypt led to the Orabi Revolt, "weakening" the power of the Egyptian monarchy, and eventually leading to the occupation of Egypt by the United Kingdom. At the same time, religious-nationalist fervour in Sudan erupted in the Mahdist Uprising led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad, and resulting in the establishment of the Caliphate of Omdurman. The Mahdist forces were eventually defeated by a joint Egyptian-British military force, restoring the authority of the Egyptian monarch. However, Egyptian sovereignty in Sudan would henceforth be rather nominal, as the true power in both Egypt and Sudan was now the United Kingdom. In 1899, under British pressure, Egypt agreed to share sovereignty over Sudan with the United Kingdom as a condominium. In effect, Sudan was governed as a British possession. The 20th century saw the growth of both Egyptian and Sudanese nationalism focusing on ending the United Kingdom's occupation. The Egyptian revolution of 1952 toppled the monarchy and demanded the withdrawal of British forces from all of Egypt and Sudan. Muhammad Naguib, one of the two co-leaders of the revolution, and Egypt's first President, who was half-Sudanese and had been raised in Sudan, made securing Sudanese independence a priority of the revolutionary government. The following year, under Egyptian and Sudanese pressure, the United Kingdom agreed to Egypt's demand for both governments to terminate their shared sovereignty over Sudan and to grant Sudan independence. On 1 January 1956, Sudan was duly declared an independent state.

After Sudan became independent, a democratic parliamentary system was established in Sudan, interrupted by multiple military coups led by either left or right radicals from communist regime in early Nimeiry years, to Islamist radicals in Al-Bashir's regime. The Jaafar Nimeiry regime began Islamist rule. This exacerbated the rift between the Islamic North, the seat of the government, and the Animists and Christians in the South. Differences in language, religion, and political power erupted in a civil war between government forces, influenced by the National Islamic Front (NIF), and the southern rebels, whose most influential faction was the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), which eventually led to the independence of South Sudan in 2011. Between 1989 and 2019, Sudan experienced a 30-year-long military dictatorship led by Omar al-Bashir, who was accused of human rights abuses, including torture, persecution of minorities, allegations of sponsoring global terrorism, and ethnic genocide due to its actions in the War in the Darfur region that broke out in 2003. Overall, the regime's actions killed an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people. Protests erupted in 2018, demanding Bashir's resignation, which resulted in a coup d'état on 11 April 2019 and Bashir's imprisonment.

Islam was Sudan's state religion and Islamic laws were applied from 1983 until 2020 when the country became a secular state. Sudan is a developing country, and ranks 172nd on the Human Development Index as of 2022. Sudan has a lower-middle income economy which largely relies on agriculture due to long-term international sanctions and isolation, as well as a long history of internal instability and factional violence. Over 35% of Sudan's population lives in poverty. Sudan is a member of the United Nations, the Arab League, African Union, COMESA, Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

More about Sudan

- Currency Sudanese pound

- Calling code +249

- Internet domain .sd

- Mains voltage 230V/50Hz

- Democracy index 2.54

- Population 30894000

- Area 1886068

- Driving side right

- Prehistoric Sudan (before c....Read morePrehistoric Sudan (before c. 8000 BC)Read less

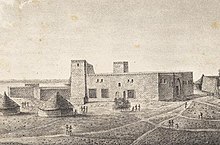

The large mud brick temple, known as the Western Deffufa, in the ancient city of Kerma

The large mud brick temple, known as the Western Deffufa, in the ancient city of Kerma Fortress of Buhen, of the Middle Kingdom, reconstructed under the New Kingdom (about 1200 BC)

Fortress of Buhen, of the Middle Kingdom, reconstructed under the New Kingdom (about 1200 BC)By the eighth millennium BC, people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mudbrick villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding.[1] Neolithic peoples created cemeteries such as R12. During the fifth millennium BC, migrations from the drying Sahara brought neolithic people into the Nile Valley along with agriculture. The population that resulted from this cultural and genetic mixing developed a social hierarchy over the next centuries which became the Kingdom of Kush (with the capital at Kerma) at 1700 BC. Anthropological and archaeological research indicate that during the predynastic period Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were ethnically, and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 BC.[2]

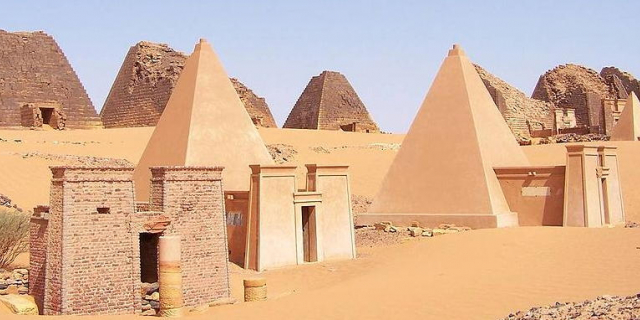

Kingdom of Kush (c. 1070 BC–350 AD)Nubian pyramids in Meroë Kušiya soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I tomb relief.

Kušiya soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I tomb relief.The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient Nubian state centered on the confluences of the Blue Nile and White Nile, and the Atbarah River and the Nile River. It was established after the Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt; it was centered at Napata in its early phase.[3]

After King Kashta ("the Kushite") invaded Egypt in the eighth century BC, the Kushite kings ruled as pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt for nearly a century before being defeated and driven out by the Assyrians.[4] At the height of their glory, the Kushites conquered an empire that stretched from what is now known as South Kordofan to the Sinai. Pharaoh Piye attempted to expand the empire into the Near East but was thwarted by the Assyrian king Sargon II.

Between 800 BCE and 100 AD were built the Nubian pyramids, among them can be named El-Kurru, Kashta, Piye, Tantamani, Shabaka, Pyramids of Gebel Barkal, Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah), the Sedeinga pyramids, and Pyramids of Nuri.[5]

The Kingdom of Kush is mentioned in the Bible as having saved the Israelites from the wrath of the Assyrians, although disease among the besiegers might have been one of the reasons for the failure to take the city.[6][page needed] The war that took place between Pharaoh Taharqa and the Assyrian king Sennacherib was a decisive event in western history, with the Nubians being defeated in their attempts to gain a foothold in the Near East by Assyria. Sennacherib's successor Esarhaddon went further and invaded Egypt itself to secure his control of the Levant. This succeeded, as he managed to expel Taharqa from Lower Egypt. Taharqa fled back to Upper Egypt and Nubia, where he died two years later. Lower Egypt came under Assyrian vassalage but proved unruly, unsuccessfully rebelling against the Assyrians. Then, the king Tantamani, a successor of Taharqa, made a final determined attempt to regain Lower Egypt from the newly reinstated Assyrian vassal Necho I. He managed to retake Memphis killing Necho in the process and besieged cities in the Nile Delta. Ashurbanipal, who had succeeded Esarhaddon, sent a large army in Egypt to regain control. He routed Tantamani near Memphis and, pursuing him, sacked Thebes. Although the Assyrians immediately departed Upper Egypt after these events, weakened, Thebes peacefully submitted itself to Necho's son Psamtik I less than a decade later. This ended all hopes of a revival of the Nubian Empire, which rather continued in the form of a smaller kingdom centered on Napata. The city was raided by the Egyptian c. 590 BC, and sometime soon after to the late-3rd century BC, the Kushite resettled in Meroë.[4][7][8]

Medieval Christian Nubian kingdoms (c. 350–1500) The three Christian Nubian kingdoms. The northern border of Alodia is unclear, but it also might have been located further north, between the fourth and fifth Nile cataract.[9]

The three Christian Nubian kingdoms. The northern border of Alodia is unclear, but it also might have been located further north, between the fourth and fifth Nile cataract.[9]On the turn of the fifth century the Blemmyes established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, probably centered around Talmis (Kalabsha), but before 450 they were already driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians. The latter eventually founded a kingdom on their own, Nobatia.[10] By the sixth century there were in total three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, which had its capital at Pachoras (Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria centred at Tungul (Old Dongola), about 13 kilometres (8 miles) south of modern Dongola; and Alodia, in the heartland of the old Kushitic kingdom, which had its capital at Soba (now a suburb of modern-day Khartoum).[11] Still in the sixth century they converted to Christianity.[12] In the seventh century, probably at some point between 628 and 642, Nobatia was incorporated into Makuria.[13]

Between 639 and 641 the Muslim Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Byzantine Egypt. In 641 or 642 and again in 652 they invaded Nubia but were repelled, making the Nubians one of the few who managed to defeat the Arabs during the Islamic expansion. Afterward the Makurian king and the Arabs agreed on a unique non-aggression pact that also included an annual exchange of gifts, thus acknowledging Makuria's independence.[14] While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia they began to settle east of the Nile, where they eventually founded several port towns[15] and intermarried with the local Beja.[16]

Moses George, king of Makuria and Alodia

Moses George, king of Makuria and AlodiaFrom the mid eighth to mid eleventh century the political power and cultural development of Christian Nubia peaked.[17] In 747 Makuria invaded Egypt, which at this time belonged to the declining Umayyads,[18] and it did so again in the early 960s, when it pushed as far north as Akhmim.[19] Makuria maintained close dynastic ties with Alodia, perhaps resulting in the temporary unification of the two kingdoms into one state.[20] The culture of the medieval Nubians has been described as "Afro-Byzantine",[21] but was also increasingly influenced by Arab culture.[22] The state organisation was extremely centralised,[23] being based on the Byzantine bureaucracy of the sixth and seventh centuries.[24] Arts flourished in the form of pottery paintings[25] and especially wall paintings.[26] The Nubians developed an alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin, basing it on the Coptic alphabet, while also using Greek, Coptic and Arabic.[27] Women enjoyed high social status: they had access to education, could own, buy and sell land and often used their wealth to endow churches and church paintings.[28] Even the royal succession was matrilineal, with the son of the king's sister being the rightful heir.[29]

From the late 11th/12th century, Makuria's capital Dongola was in decline, and Alodia's capital declined in the 12th century as well.[30] In the 14th and 15th centuries Bedouin tribes overran most of Sudan,[31] migrating to the Butana, the Gezira, Kordofan and Darfur.[32] In 1365 a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia, while Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. Afterwards Makuria continued to exist only as a petty kingdom.[33] After the prosperous[34] reign of king Joel (fl. 1463–1484) Makuria collapsed.[35] Coastal areas from southern Sudan up to the port city of Suakin was succeeded by the Adal Sultanate in the fifteenth century.[36][37] To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either the Arabs, commanded by tribal leader Abdallah Jamma, or the Funj, an African people originating from the south.[38] Datings range from the 9th century after the Hijra (c. 1396–1494),[39] the late 15th century,[40] 1504[41] to 1509.[42] An alodian rump state might have survived in the form of the kingdom of Fazughli, lasting until 1685.[43]

Islamic kingdoms of Sennar and Darfur (c. 1500–1821) The great mosque of Sennar, built in the 17th century[44]

The great mosque of Sennar, built in the 17th century[44]In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the Kingdom of Sennar, in which Abdallah Jamma's realm was incorporated.[45] By 1523, when Jewish traveler David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already extended as far north as Dongola.[46] Meanwhile, Islam began to be preached on the Nile by Sufi holy men who settled there in the 15th and 16th centuries[47] and by David Reubeni's visit king Amara Dunqas, previously a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim.[48] However, the Funj would retain un-Islamic customs like the divine kingship or the consumption of alcohol until the 18th century.[49] Sudanese folk Islam preserved many rituals stemming from Christian traditions until the recent past.[50]

Soon the Funj came in conflict with the Ottomans, who had occupied Suakin around 1526[51] and eventually pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area in 1583/1584. A subsequent Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola was repelled by the Funj in 1585.[52] Afterwards, Hannik, located just south of the third cataract, would mark the border between the two states.[53] The aftermath of the Ottoman invasion saw the attempted usurpation of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. While the Funj eventually killed him in 1611/1612 his successors, the Abdallab, were granted to govern everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Niles with considerable autonomy.[54]

During the 17th century the Funj state reached its widest extent,[55] but in the following century it began to decline.[56] A coup in 1718 brought a dynastic change,[57] while another one in 1761–1762[58] resulted in the Hamaj Regency, where the Hamaj (a people from the Ethiopian borderlands) effectively ruled while the Funj sultans were their mere puppets.[59] Shortly afterwards the sultanate began to fragment;[60] by the early 19th century it was essentially restricted to the Gezira.[61]

Southern Sudan in c. 1800. Modern boundaries are shown.

Southern Sudan in c. 1800. Modern boundaries are shown.The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the Arabisation of the state.[62] To legitimise their rule over their Arab subjects the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descend.[63] North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin.[64] Until the 19th century Arabic had succeeded in becoming the dominant language of central riverine Sudan[65][66][67] and most of Kordofan.[68]

West of the Nile, in Darfur, the Islamic period saw at first the rise of the Tunjur kingdom, which replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 15th century[69] and extended as far west as Wadai.[70] The Tunjur people were probably Arabised Berbers and, their ruling elite at least, Muslims.[71] In the 17th century the Tunjur were driven from power by the Fur Keira sultanate.[70] The Keira state, nominally Muslim since the reign of Sulayman Solong (r. c. 1660–1680),[72] was initially a small kingdom in northern Jebel Marra,[73] but expanded west- and northwards in the early 18th century[74] and eastwards under the rule of Muhammad Tayrab (r. 1751–1786),[75] peaking in the conquest of Kordofan in 1785.[76] The apogee of this empire, now roughly the size of present-day Nigeria,[76] would last until 1821.[75]

Turkiyah and Mahdist Sudan (1821–1899)Ismail Pasha, the Ottoman Khedive of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879 Muhammad Ahmad, ruler of Sudan (1881–1885)

Muhammad Ahmad, ruler of Sudan (1881–1885)In 1821, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali of Egypt, had invaded and conquered northern Sudan. Although technically the Vali of Egypt under the Ottoman Empire, Muhammad Ali styled himself as Khedive of a virtually independent Egypt. Seeking to add Sudan to his domains, he sent his third son Ismail (not to be confused with Ismaʻil Pasha mentioned later) to conquer the country, and subsequently incorporate it into Egypt. With the exception of the Shaiqiya and the Darfur sultanate in Kordofan, he was met without resistance. The Egyptian policy of conquest was expanded and intensified by Ibrahim Pasha's son, Ismaʻil, under whose reign most of the remainder of modern-day Sudan was conquered.

The Egyptian authorities made significant improvements to the Sudanese infrastructure (mainly in the north), especially with regard to irrigation and cotton production. In 1879, the Great Powers forced the removal of Ismail and established his son Tewfik Pasha in his place. Tewfik's corruption and mismanagement resulted in the 'Urabi revolt, which threatened the Khedive's survival. Tewfik appealed for help to the British, who subsequently occupied Egypt in 1882. Sudan was left in the hands of the Khedivial government, and the mismanagement and corruption of its officials.[77][78]

During the Khedivial period, dissent had spread due to harsh taxes imposed on most activities. Taxation on irrigation wells and farming lands were so high most farmers abandoned their farms and livestock. During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade had an adverse impact on the economy of northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces.[79] Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abd Allah, the Mahdi (Guided One), offered to the ansars (his followers) and those who surrendered to him a choice between adopting Islam or being killed. The Mahdiyah (Mahdist regime) imposed traditional Sharia Islamic laws. On 12 August 1881, an incident occurred at Aba Island, sparking the outbreak of what became the Mahdist War.

From his announcement of the Mahdiyya in June 1881 until the fall of Khartoum in January 1885, Muhammad Ahmad led a successful military campaign against the Turco-Egyptian government of the Sudan, known as the Turkiyah. Muhammad Ahmad died on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of Khartoum. After a power struggle amongst his deputies, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, with the help primarily of the Baggara of western Sudan, overcame the opposition of the others and emerged as the unchallenged leader of the Mahdiyah. After consolidating his power, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad assumed the title of Khalifa (successor) of the Mahdi, instituted an administration, and appointed Ansar (who were usually Baggara) as emirs over each of the several provinces.

The flight of the Khalifa after his defeat at the Battle of OmdurmanRegional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's brutal methods to extend his rule throughout the country. In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrating as far as Gondar. In March 1889, king Yohannes IV of Ethiopia marched on Metemma; however, after Yohannes fell in battle, the Ethiopian forces withdrew. Abd ar-Rahman an-Nujumi, the Khalifa's general, attempted an invasion of Egypt in 1889, but British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. The failure of the Egyptian invasion broke the spell of the Ansar's invincibility. The Belgians prevented the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria, and in 1893, the Italians repelled an Ansar attack at Agordat (in Eritrea) and forced the Ansar to withdraw from Ethiopia.

In the 1890s, the British sought to re-establish their control over Sudan, once more officially in the name of the Egyptian Khedive, but in actuality treating the country as a British colony. By the early 1890s, British, French, and Belgian claims had converged at the Nile headwaters. Britain feared that the other powers would take advantage of Sudan's instability to acquire territory previously annexed to Egypt. Apart from these political considerations, Britain wanted to establish control over the Nile to safeguard a planned irrigation dam at Aswan. Herbert Kitchener led military campaigns against the Mahdist Sudan from 1896 to 1898. Kitchener's campaigns culminated in a decisive victory in the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898. A year later, the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat on 25 November 1899 resulted in the death of Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, subsequently bringing to the end of the Mahdist War.

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956) The Mahdist War was fought between a group of Muslim dervishes, called Mahdists, who had over-run much of Sudan, and the British forces.

The Mahdist War was fought between a group of Muslim dervishes, called Mahdists, who had over-run much of Sudan, and the British forces.In 1899, Britain and Egypt reached an agreement under which Sudan was run by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent.[80] In reality, Sudan was effectively administered as a Crown colony. The British were keen to reverse the process, started under Muhammad Ali Pasha, of uniting the Nile Valley under Egyptian leadership and sought to frustrate all efforts aimed at further uniting the two countries.[citation needed]

Under the Delimitation, Sudan's border with Abyssinia was contested by raiding tribesmen trading slaves, breaching boundaries of the law. In 1905 Local chieftain Sultan Yambio reluctant to the end gave up the struggle with British forces that had occupied the Kordofan region, finally ending the lawlessness. The continued British administration of Sudan fuelled an increasingly strident nationalist backlash, with Egyptian nationalist leaders determined to force Britain to recognise a single independent union of Egypt and Sudan. With a formal end to Ottoman rule in 1914, Sir Reginald Wingate was sent that December to occupy Sudan as the new Military Governor. Hussein Kamel was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, as was his brother and successor, Fuad I. They continued upon their insistence of a single Egyptian-Sudanese state even when the Sultanate of Egypt was retitled as the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan, but it was Saad Zaghloul who continued to be frustrated in the ambitions until his death in 1927.[81]

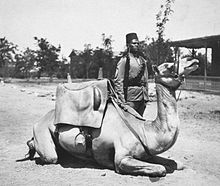

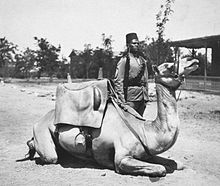

A camel soldier of the native forces of the British army, early 20th century

A camel soldier of the native forces of the British army, early 20th centuryFrom 1924 until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate territories; the north and south. The assassination of a Governor-General of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in Cairo was the causative factor; it brought demands of the newly elected Wafd government from colonial forces. A permanent establishment of two battalions in Khartoum was renamed the Sudan Defence Force acting as under the government, replacing the former garrison of Egyptian army soldiers, saw action afterward during the Walwal Incident.[82] The Wafdist parliamentary majority had rejected Sarwat Pasha's accommodation plan with Austen Chamberlain in London; yet Cairo still needed the money. The Sudanese Government's revenue had reached a peak in 1928 at £6.6 million, thereafter the Wafdist disruptions, and Italian borders incursions from Somaliland, London decided to reduce expenditure during the Great Depression. Cotton and gum exports were dwarfed by the necessity to import almost everything from Britain leading to a balance of payments deficit at Khartoum.[83]

In July 1936 the Liberal Constitutional leader, Muhammed Mahmoud was persuaded to bring Wafd delegates to London to sign the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, "the beginning of a new stage in Anglo-Egyptian relations", wrote Anthony Eden.[84] The British Army was allowed to return to Sudan to protect the Canal Zone. They were able to find training facilities, and the RAF was free to fly over Egyptian territory. It did not, however, resolve the problem of Sudan: the Sudanese Intelligentsia agitated for a return to metropolitan rule, conspiring with Germany's agents.[85]

Mussolini made it clear that he could not invade Abyssinia without first conquering Egypt and Sudan; they intended unification of Libya with Italian East Africa. The British Imperial General Staff prepared for military defence of the region, which was thin on the ground.[86] The British ambassador blocked Italian attempts to secure a Non-Aggression Treaty with Egypt-Sudan. But Mahmoud was a supporter of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem; the region was caught between the Empire's efforts to save the Jews, and moderate Arab calls to halt migration.[87]

The Sudanese Government was directly involved militarily in the East African Campaign. Formed in 1925, the Sudan Defence Force played an active part in responding to incursions early in World War Two. Italian troops occupied Kassala and other border areas from Italian Somaliland during 1940. In 1942, the SDF also played a part in the invasion of the Italian colony by British and Commonwealth forces. The last British governor-general was Robert George Howe.

The Egyptian revolution of 1952 finally heralded the beginning of the march towards Sudanese independence. Having abolished the monarchy in 1953, Egypt's new leaders, Mohammed Naguib, whose mother was Sudanese, and later Gamal Abdel Nasser, believed the only way to end British domination in Sudan was for Egypt to officially abandon its claims of sovereignty. In addition, Nasser knew it would be difficult for Egypt to govern an impoverished Sudan after its independence. The British on the other hand continued their political and financial support for the Mahdist successor, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, whom it was believed would resist Egyptian pressure for Sudanese independence. Rahman was capable of this, but his regime was plagued by political ineptitude, which garnered a colossal loss of support in northern and central Sudan. Both Egypt and Britain sensed a great instability fomenting, and thus opted to allow both Sudanese regions, north and south to have a free vote on whether they wished independence or a British withdrawal.

Independence (1956–present)This section is missing information about the history of Sudan between 1956 and 1969 and between 1977 and 1989. (January 2016) Sudan's flag raised at independence ceremony on 1 January 1956 by the Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari and in presence of opposition leader Mohamed Ahmed Almahjoub.

Sudan's flag raised at independence ceremony on 1 January 1956 by the Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari and in presence of opposition leader Mohamed Ahmed Almahjoub.A polling process was carried out resulting in the composition of a democratic parliament and Ismail al-Azhari was elected first Prime Minister and led the first modern Sudanese government.[88] On 1 January 1956, in a special ceremony held at the People's Palace, the Egyptian and British flags were lowered and the new Sudanese flag, composed of green, blue and yellow stripes, was raised in their place by the prime minister Ismail al-Azhari.

Dissatisfaction culminated in a second coup d'état on 25 May 1969. The coup leader, Col. Gaafar Nimeiry, became prime minister, and the new regime abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties. Disputes between Marxist and non-Marxist elements within the ruling military coalition resulted in a briefly successful coup in July 1971, led by the Sudanese Communist Party. Several days later, anti-communist military elements restored Nimeiry to power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a cessation of the north–south civil war and a degree of self-rule. This led to ten years hiatus in the civil war but an end to American investment in the Jonglei Canal project. This had been considered absolutely essential to irrigate the Upper Nile region and to prevent an environmental catastrophe and wide-scale famine among the local tribes, most especially the Dinka. In the civil war that followed their homeland was raided, looted, pillaged, and burned. Many of the tribe were murdered in a bloody civil war that raged for over 20 years.

1971 Sudanese coup d'état

1971 Sudanese coup d'étatUntil the early 1970s, Sudan's agricultural output was mostly dedicated to internal consumption. In 1972, the Sudanese government became more pro-Western and made plans to export food and cash crops. However, commodity prices declined throughout the 1970s causing economic problems for Sudan. At the same time, debt servicing costs, from the money spent mechanizing agriculture, rose. In 1978, the IMF negotiated a Structural Adjustment Program with the government. This further promoted the mechanised export agriculture sector. This caused great hardship for the pastoralists of Sudan (see Nuba peoples). In 1976, the Ansars had mounted a bloody but unsuccessful coup attempt. But in July 1977, President Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, opening the way for a possible reconciliation. Hundreds of political prisoners were released, and in August a general amnesty was announced for all oppositionists.

Bashir era (1989–2019) Omar al-Bashir in 2017

Omar al-Bashir in 2017On 30 June 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir led a bloodless military coup.[89] The new military government suspended political parties and introduced an Islamic legal code on the national level.[90] Later, al-Bashir carried out purges and executions in the upper ranks of the army, the banning of associations, political parties, and independent newspapers, and the imprisonment of leading political figures and journalists.[91] On 16 October 1993, al-Bashir appointed himself "President" and disbanded the Revolutionary Command Council. The executive and legislative powers of the council were taken by al-Bashir.[92]

In the 1996 general election, he was the only candidate by law to run for election.[93] Sudan became a one-party state under the National Congress Party (NCP).[94] During the 1990s, Hassan al-Turabi, then Speaker of the National Assembly, reached out to Islamic fundamentalist groups and invited Osama bin Laden to the country.[95] The United States subsequently listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism.[96] Following Al Qaeda's bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the U.S. launched Operation Infinite Reach and targeted the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, which the U.S. government falsely believed was producing chemical weapons for the terrorist group. Al-Turabi's influence began to wane, and others in favour of more pragmatic leadership tried to change Sudan's international isolation.[97] The country worked to appease its critics by expelling members of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and encouraging bin Laden to leave.[98]

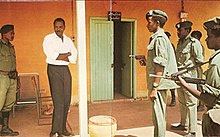

Government militia in DarfurBefore the 2000 presidential election, al-Turabi introduced a bill to reduce the President's powers, prompting al-Bashir to order a dissolution and declare a state of emergency. When al-Turabi urged a boycott of the President's re-election campaign signing agreement with Sudan People's Liberation Army, al-Bashir suspected they were plotting to overthrow the government.[99] Hassan al-Turabi was jailed later the same year.[100]

In February 2003, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) groups in Darfur took up arms, accusing the Sudanese government of oppressing non-Arab Sudanese in favor of Sudanese Arabs, precipitating the War in Darfur. The conflict has since been described as a genocide,[101] and the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague has issued two arrest warrants for al-Bashir.[102][103] Arabic-speaking nomadic militias known as the Janjaweed stand accused of many atrocities.

On 9 January 2005, the government signed the Nairobi Comprehensive Peace Agreement with the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) with the objective of ending the Second Sudanese Civil War. The United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) was established under the UN Security Council Resolution 1590 to support its implementation. The peace agreement was a prerequisite to the 2011 referendum: the result was a unanimous vote in favour of secession of South Sudan; the region of Abyei will hold its own referendum at a future date.

Southern Sudanese wait to vote during the 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum.

Southern Sudanese wait to vote during the 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum.The Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) was the primary member of the Eastern Front, a coalition of rebel groups operating in eastern Sudan. After the peace agreement, their place was taken in February 2004 after the merger of the larger fulani and Beja Congress with the smaller Rashaida Free Lions.[104] A peace agreement between the Sudanese government and the Eastern Front was signed on 14 October 2006, in Asmara. On 5 May 2006, the Darfur Peace Agreement was signed, aiming at ending the conflict which had continued for three years up to this point.[105] The Chad–Sudan Conflict (2005–2007) had erupted after the Battle of Adré triggered a declaration of war by Chad.[106] The leaders of Sudan and Chad signed an agreement in Saudi Arabia on 3 May 2007 to stop fighting from the Darfur conflict spilling along their countries' 1,000-kilometre (600 mi) border.[107]

In July 2007 the country was hit by devastating floods,[108] with over 400,000 people being directly affected.[109] Since 2009, a series of ongoing conflicts between rival nomadic tribes in Sudan and South Sudan have caused a large number of civilian casualties.

Partition and rehabilitationThe Sudanese conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile in the early 2010s between the Army of Sudan and the Sudan Revolutionary Front started as a dispute over the oil-rich region of Abyei in the months leading up to South Sudanese independence in 2011, though it is also related to civil war in Darfur that is nominally resolved. The events would later be known as the Sudanese Intifada, which would end only in 2013 after al-Bashir promised he would not seek re-election in 2015. He later broke his promise and sought re-election in 2015, winning through a boycott from the opposition who believed that the elections would not be free and fair. Voter turnout was at a low 46%.[110]

On 13 January 2017, US president Barack Obama signed an Executive Order that lifted many sanctions placed against Sudan and assets of its government held abroad. On 6 October 2017, the following US president Donald Trump lifted most of the remaining sanctions against the country and its petroleum, export-import, and property industries.[111]

2019 Sudanese Revolution and transitional government Sudanese protestors celebrate the 17 August 2019 signing of the Draft Constitutional Declaration between military and civilian representatives.

Sudanese protestors celebrate the 17 August 2019 signing of the Draft Constitutional Declaration between military and civilian representatives.On 19 December 2018, massive protests began after a government decision to triple the price of goods at a time when the country was suffering an acute shortage of foreign currency and inflation of 70 percent.[112] In addition, President al-Bashir, who had been in power for more than 30 years, refused to step down, resulting in the convergence of opposition groups to form a united coalition. The government retaliated by arresting more than 800 opposition figures and protesters, leading to the death of approximately 40 people according to the Human Rights Watch,[113] although the number was much higher than that according to local and civilian reports. The protests continued after the overthrow of his government on 11 April 2019 after a massive sit-in in front of the Sudanese Armed Forces main headquarters, after which the chiefs of staff decided to intervene and they ordered the arrest of President al-Bashir and declared a three-month state of emergency.[114][115][116] Over 100 people died on 3 June after security forces dispersed the sit-in using tear gas and live ammunition in what is known as the Khartoum massacre,[117][118] resulting in Sudan's suspension from the African Union.[119] Sudan's youth had been reported to be driving the protests.[120] The protests came to an end when the Forces for Freedom and Change (an alliance of groups organizing the protests) and Transitional Military Council (the ruling military government) signed the July 2019 Political Agreement and the August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration.[121][122]

Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan with Israel's Minister of Intelligence, Eli Cohen, in January 2021

Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan with Israel's Minister of Intelligence, Eli Cohen, in January 2021The transitional institutions and procedures included the creation of a joint military-civilian Sovereignty Council of Sudan as head of state, a new Chief Justice of Sudan as head of the judiciary branch of power, Nemat Abdullah Khair, and a new prime minister. The former Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, a 61-year-old economist who worked previously for the UN Economic Commission for Africa, was sworn in on 21 August. He initiated talks with the IMF and World Bank aimed at stabilising the economy, which was in dire straits because of shortages of food, fuel and hard currency. Hamdok estimated that US$10bn over two years would suffice to halt the panic, and said that over 70% of the 2018 budget had been spent on civil war-related measures. The governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had invested significant sums supporting the military council since Bashir's ouster.[123] On 3 September, Hamdok appointed 14 civilian ministers, including the first female foreign minister and the first Coptic Christian, also a woman.[124][125] As of August 2021, the country was jointly led by Chairman of the Transitional Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok.[126]

2021 coup and the al-Burhan regimeThe Sudanese government announced on 21 September 2021 that there was a failed attempt at a coup d’état from the military that had led to the arrest of 40 military officers.[127][128]

One month after the attempted coup, another military coup on 25 October 2021 resulted in the capture of the civilian government, including former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. The coup was led by general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan who subsequently declared a state of emergency.[129][130][131][132]

On 21 November 2021, Hamdok was reinstated as prime minister after a political agreement was signed by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to restore the transition to civilian rule (although Burhan retained control). The 14-point deal called for the release of all political prisoners detained during the coup and stipulated that a 2019 constitutional declaration continued to be the basis for a political transition.[133] Hamdok fired the chief of police Khaled Mahdi Ibrahim al-Emam and his second in command Ali Ibrahim.[134]

On 2 January 2022, Hamdok announced his resignation from the position of Prime Minister following one of the most deadly protests to date.[135]

By March 2022 over 1,000 people including 148 children had been detained for opposing the coup, there were 25 allegations of rape[136] and 87 people had been killed[137] including 11 children.[136]

2023 rebellionIn April 2023 – as an internationally-brokered plan for a transition to civilian rule was discussed – power struggles grew between army commander (and de facto national leader) Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and his deputy, Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, head of the heavily-armed paramilitary Rapid Support Forces & Rapid Strike Force ("RSF"), formed from the Janjaweed militia.[138][139]

On 15 April 2023, their conflict erupted into intensely violent open battles in the streets of Khartoum between the army and the RSF – with troops, tanks and planes. By the third day, nearly 200 people had been reported killed and at least 1,800 injured, according to the United Nations.[140] Among the dead were three workers from the World Food Program, triggering a suspension of the organization's work in Sudan, despite ongoing hunger afflicting much of the country. U.N. secretary-general António Guterres demanded immediate "justice" for the killings, and called for an end to the conflict.[138][139] [141]

African Union and Saudi diplomats headed to Sudan to attempt to mediate a cease-fire. A brief cease fire (3–4 hours) was declared to permit evacuation of wounded, but the battle raged on, with both sides claiming conquest of key sites throughout the capital city.[138][139]

^ "Sudan A Country Study". Countrystudies.us. ^ Keita, S.O.Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20 (7): 129–54. doi:10.2307/3171969. JSTOR 317196. S2CID 162330365. ^ Edwards, David N. (2005). Nubian Past : an Archaeology of the Sudan. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-48276-6. OCLC 437079538. ^ a b Emberling, Geoff; Davis, Suzanne (2019). "A Cultural History of Kush: Politics, Economy, and Ritual Practice". Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond (PDF). Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. pp. 5–6, 10–11. ISBN 978-0-9906623-9-6. Retrieved 3 November 2021. ^ Takacs, Sarolta Anna; Cline, Eric H. (17 July 2015). The Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45839-5. ^ Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-193825-7. ^ Connah, Graham (2004). Forgotten Africa: An Introduction to Its Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-415-30590-X. Retrieved 3 November 2021. ^ Unseth, Peter (1 July 1998). "Semantic Shift on a Geographical Term". The Bible Translator. 49 (3): 323–324. doi:10.1177/026009359804900302. S2CID 131916337. ^ Welsby 2002, p. 26. ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 16–22. ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 24, 26. ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 16–17. ^ Werner 2013, p. 77. ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 68–70. ^ Hasan 1967, p. 31. ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 77–78. ^ Shinnie 1978, p. 572. ^ Werner 2013, p. 84. ^ Werner 2013, p. 101. ^ Welsby 2002, p. 89. ^ Ruffini 2012, p. 264. ^ Martens-Czarnecka 2015, pp. 249–265. ^ Werner 2013, p. 254. ^ Edwards 2004, p. 237. ^ Adams 1977, p. 496. ^ Adams 1977, p. 482. ^ Welsby 2002, pp. 236–239. ^ Werner 2013, pp. 344–345. ^ Welsby 2002, p. 88. ^ Welsby 2002, p. 252. ^ Hasan 1967, p. 176. ^ Hasan 1967, p. 145. ^ Werner 2013, pp. 143–145. ^ Lajtar 2011, pp. 130–131. ^ Ruffini 2012, p. 256. ^ Owens, Travis (June 2008). Beleaguered Muslim Fortresses And Ethiopian Imperial Expansion From The 13th To The 16th Century (PDF) (Masters). Naval Postgraduate School. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020. ^ Levtzion & Pouwels 2000, p. 229. ^ Welsby 2002, p. 255. ^ Vantini 1975, pp. 786–787. ^ Hasan 1967, p. 133. ^ Vantini 1975, p. 784. ^ Vantini 2006, pp. 487–489. ^ Spaulding 1974, pp. 12–30. ^ Holt & Daly 2000, p. 25. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 25–26. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 26. ^ Loimeier 2013, p. 150. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 31. ^ Loimeier 2013, pp. 151–152. ^ Werner 2013, pp. 177–184. ^ Peacock 2012, p. 98. ^ Peacock 2012, pp. 96–97. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 35. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 36–40. ^ Adams 1977, p. 601. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 78. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 88. ^ Spaulding 1974, p. 24-25. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 94–95. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 98. ^ Spaulding 1985, p. 382. ^ Loimeier 2013, p. 152. ^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 210–212. ^ Adams 1977, pp. 557–558. ^ Edwards 2004, p. 260. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 28–29. ^ Hesse 2002, p. 50. ^ Hesse 2002, pp. 21–22. ^ McGregor 2011, Table 1. ^ a b O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 110. ^ McGregor 2011, p. 132. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 123. ^ Holt & Daly 2000, p. 31. ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 126. ^ a b O'Fahey & Tubiana 2007, p. 9. ^ a b O'Fahey & Tubiana 2007, p. 2. ^ Churchill 1902, p. [page needed]. ^ Rudolf Carl Freiherr von Slatin; Sir Francis Reginald Wingate (1896). Fire and Sword in the Sudan. E. Arnold. Retrieved 26 June 2013. ^ Domke, D. Michelle (November 1997). "ICE Case Studies; Case Number: 3; Case Identifier: Sudan; Case Name: Civil War in the Sudan: Resources or Religion?". Inventory of Conflict and Environment. Archived from the original on 9 December 2000. Retrieved 8 January 2011 – via American University School of International Service. ^ Humphries, Christian (2001). Oxford World Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 644. ISBN 0195218183. ^ Daly, p. 346. ^ Morewood 2005, p. 4. ^ Daly, pp. 457–459. ^ Morewood 1940, pp. 94–95. ^ Arthur Henderson, 8 May 1936 quoted in Daly, p. 348 ^ Sir Miles Lampson, 29 September 1938; Morewood, p. 117 ^ Morewood, pp. 164–165. ^ "Brief History of the Sudan". Sudan Embassy in London. 20 November 2008. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2013. ^ "Factbox – Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir". Reuters. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2011. ^ Bekele, Yilma (12 July 2008). "Chickens Are Coming Home To Roost!". Ethiopian Review. Addis Ababa. Retrieved 13 January 2011. ^ Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-674-01090-1. ^ Walker, Peter (14 July 2008). "Profile: Omar al-Bashir". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 January 2011. ^ The New York Times. 16 March 1996. p. 4. ^ "History of the Sudan". HistoryWorld. n.d. Retrieved 13 January 2011. ^ Shahzad, Syed Saleem (23 February 2002). "Bin Laden Uses Iraq To Plot New Attacks". Asia Times. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 20 October 2002. Retrieved 14 January 2011.{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) ^ "Families of USS Cole Victims Sue Sudan for $105 Million". Fox News Channel. Associated Press. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2011. ^ Fuller, Graham E. (2004). The Future of Political Islam. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4039-6556-1. ^ Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 221–223. ISBN 978-0-307-26608-8. ^ "Profile: Sudan's President Bashir". BBC News. 25 November 2003. Retrieved 8 January 2011. ^ Ali, Wasil (12 May 2008). "Sudanese Islamist Opposition Leader Denies Link with Darfur Rebels". Sudan Tribune. Paris. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2013. ^ "ICC Prosecutor Presents Case Against Sudanese President, Hassan Ahmad al Bashir, for Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes in Darfur" (Press release). Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court. 14 July 2008. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. ^ "Warrant issued for Sudan's Bashir". BBC News. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2011. ^ Lynch, Colum; Hamilton, Rebecca (13 July 2010). "International Criminal Court Charges Sudan's Omar Hassan al-Bashir with Genocide". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 January 2011.[permanent dead link] ^ "UNMIS Media Monitoring Report" (PDF). United Nations Mission in Sudan. 4 January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2006. ^ "Darfur Peace Agreement". US Department of State. 8 May 2006. ^ "Restraint Plea to Sudan and Chad". Al Jazeera. Agence France-Presse. 27 December 2005. Archived from the original on 10 October 2006. ^ "Sudan, Chad Agree To Stop Fighting". China Daily. Beijing. Associated Press. 4 May 2007. ^ "UN: Situation in Sudan could deteriorate if flooding continues". International Herald Tribune. Paris. Associated Press. 6 August 2007. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. ^ "Sudan Floods: At Least 365,000 Directly Affected, Response Ongoing" (Press release). UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Relief Web. 6 August 2007. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2011. ^ "Omar al-Bashir wins Sudan elections by a landslide". BBC News. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2019. ^ Wadhams, Nick; Gebre, Samuel (6 October 2017). "Trump Moves to Lift Most Sudan Sanctions". Bloomberg Politics. Retrieved 6 October 2017. ^ "Sudan December 2018 riots: Is the regime crumbling?". CMI – Chr. Michelsen Institute. Retrieved 30 June 2019. ^ "Sudan: Protesters Killed, Injured". Human Rights Watch. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019. ^ "Sudan military coup topples Bashir". 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019. ^ "Sudan's Omar al-Bashir vows to stay in power as protests rage | News". Al Jazeera. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019. ^ Arwa Ibrahim (8 January 2019). "Future unclear as Sudan protesters and president at loggerheads | News". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 April 2019. ^ "Sudan's security forces attack long-running sit-in". BBC News. 3 June 2019. ^ ""Chaos and Fire" – An Analysis of Sudan's June 3, 2019 Khartoum Massacre – Sudan". ReliefWeb. ^ AP, Source: Reuters / (7 June 2019). "African Union suspends Sudan over violence against protestors – video". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 June 2019. {{cite news}}: |first= has generic name (help) ^ "'They'll have to kill all of us!'". BBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2019. ^ Cite error: The named reference raisethevoices_4Aug2019_const_dec was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Cite error: The named reference Const_Dec_En_unofficial was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Abdelaziz, Khalid (24 August 2019). "Sudan needs up to $10 billion in aid to rebuild economy, new PM says". The Globe and Mail. ^ "Sudan's PM selects members of first cabinet since Bashir's ouster". Reuters. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019. ^ "Women take prominent place in Sudanese politics as Abdalla Hamdok names cabinet". The National. 4 September 2019. ^ "Sudan Threatens to Use Military Option to Regain Control over Border with Ethiopia". Asharq Al-Awsat. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021. ^ "Coup attempt fails in Sudan – state media". BBC News. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021. ^ Nima Elbagir and Yasir Abdullah (21 September 2021). "Sudan foils coup attempt and 40 officers arrested, senior officials say". CNN. Retrieved 21 September 2021. ^ "Sudan's civilian leaders arrested – reports". www.msn.com. ^ "Sudan Officials Detained, Communication Lines Cut in Apparent Military Coup". Bloomberg.com. 25 October 2021. ^ "Sudan's civilian leaders arrested amid coup reports". BBC News. 25 October 2021. ^ Magdy, Samy. "Gov't officials detained, phones down in possible Sudan coup". ABC News. ^ "Sudan's Hamdok reinstated as PM after political agreement signed". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 21 November 2021. ^ Staff (27 November 2021). "Reinstated Sudanese PM Hamdok dismisses police chiefs". Al Jazeera.com. Retrieved 22 March 2022. ^ "Sudan PM Abdalla Hamdok resigns after deadly protest". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2 January 2022. ^ a b Bachelet, Michelle (7 March 2022). "Oral update on the situation of human rights in the Sudan – Statement by United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights". ReliefWeb/ 49th Session of the UN Human Rights Council. Retrieved 22 March 2022. ^ Associated Press (18 March 2022). "Sudan group says 187 wounded in latest anti-coup protests". ABC News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022. ^ a b c "Fighting continues in Sudan despite humanitarian pause," 16 April 2023, France24, retrieved 16 April 2023 ^ a b c "Clashes erupt in Sudan between army, paramilitary group over government transition," 16 April 2023, ABC News, retrieved 16 April 2023 ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/04/18/sudan-conflict-military-rsf-paramilitary/ ^ https://apnews.com/article/sudan-fighting-military-rsf-eafa3246b1e3004a1a9f2b9af9561362

- Stay safe

Safety in Sudan has many dimensions. On one hand, theft is almost unheard of, you'll never be robbed in the street and people will go to great length to ensure your well-being. On the other hand, Sudan has a long history of conflict, the government is not particularly open or accountable, and under the surface corruption is rife.

Sudan is an Islamic country and consumption of alcohol is illegal.

Armed conflictSudan was at 40-year civil war between the Khartoum based central government and non-Muslim separatist groups from the South, at the time when South Sudan was still part of Sudan. Relations between the two countries after the independence of South Sudan remain fluid and somewhat tense or complicated

The well-publicized conflict in Darfur is still taking place, making traveling to the western parts of Sudan totally inadvisable.

TransportationSudan is one of four countries worldwide that do not comply with international flight safety protocol. The fleet of the state-owned Sudan Airways is mainly composed of 1950s-era Soviet aircraft. Some planes have no navigation, lighting, or are missing critical pieces of landing gear. Sudan is a very dangerous country for internal air travel.

Entering Sudan via personal car is also challenging. Sudan has a highly militarized border with its neighbor Egypt and Westerners run into problems at the border if they wish to cross.

Bus travel is also not without its issues. Some buses are better than others - some are excellent, with icy-cold AC and complementary drinks, others may be less salubrious, e.g. sitting in a hot bus (did we mention no A/C?) with jabbering Egyptian tourists for nearly an entire day.

...Read moreStay safeRead lessSafety in Sudan has many dimensions. On one hand, theft is almost unheard of, you'll never be robbed in the street and people will go to great length to ensure your well-being. On the other hand, Sudan has a long history of conflict, the government is not particularly open or accountable, and under the surface corruption is rife.

Sudan is an Islamic country and consumption of alcohol is illegal.

Armed conflictSudan was at 40-year civil war between the Khartoum based central government and non-Muslim separatist groups from the South, at the time when South Sudan was still part of Sudan. Relations between the two countries after the independence of South Sudan remain fluid and somewhat tense or complicated

The well-publicized conflict in Darfur is still taking place, making traveling to the western parts of Sudan totally inadvisable.

TransportationSudan is one of four countries worldwide that do not comply with international flight safety protocol. The fleet of the state-owned Sudan Airways is mainly composed of 1950s-era Soviet aircraft. Some planes have no navigation, lighting, or are missing critical pieces of landing gear. Sudan is a very dangerous country for internal air travel.

Entering Sudan via personal car is also challenging. Sudan has a highly militarized border with its neighbor Egypt and Westerners run into problems at the border if they wish to cross.

Bus travel is also not without its issues. Some buses are better than others - some are excellent, with icy-cold AC and complementary drinks, others may be less salubrious, e.g. sitting in a hot bus (did we mention no A/C?) with jabbering Egyptian tourists for nearly an entire day.

Personal safetyThere is almost no likelihood of being physically attacked (mugged) for your possessions, but keep an eye on your things in public places, e.g. street cafes. Sometimes thieves operate in pairs: one distracts you while the other makes off with your stuff. There have been cases of pickpocketing in Sudan as well

Women travelersWhile solo women will raise a few eyebrows, travel may be relatively safe (in areas unaffected by civil war) if they dress and act appropriately for an Islamic country. Traditionally, women in Sudan wear loose flowing robes due to restrictive laws against wearing trousers and short or tight skirts; thousands of women are arrested and flogged for indecency every year, and laws can be applied arbitrarily.

In general, it is best for women to travel in groups, and even better, with men.

Police and armyYou will see armed policemen and military personnel everywhere but you will not have any problems with them unless you have infringed some rule, e.g., taking photographs or filming in prohibited areas. Sudanese police are sometimes known to target travelers for bribes .

PhotographySudan has very strict rules about taking pictures. As this is a Muslim-majority country, people place a huge emphasis on personal privacy.

To take pictures in Sudan, you must have a permit from the government.

Photographing or filming military personnel or installations is a quick way to get into trouble.

LGBT travellers WARNING: LGBT activities are seen as severe offences and they are punishable by lengthy prison sentences. The cultural, societal, and legal abhorrence against the LGBT community is well-documented, with more than 17% of Sudanese people saying that homosexuality is socially acceptable. Until 2020, homosexuality was punishable by death. Anti-LGBT sentiments are pervasive, and open display of LGBT behaviour may result in open contempt and/or possible violence.

Government travel advisoriesUnited Kingdom United States

WARNING: LGBT activities are seen as severe offences and they are punishable by lengthy prison sentences. The cultural, societal, and legal abhorrence against the LGBT community is well-documented, with more than 17% of Sudanese people saying that homosexuality is socially acceptable. Until 2020, homosexuality was punishable by death. Anti-LGBT sentiments are pervasive, and open display of LGBT behaviour may result in open contempt and/or possible violence.

Government travel advisoriesUnited Kingdom United States