布达拉宫

( Potala Palace )

The Potala Palace is a dzong fortress in Lhasa, capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region in China. It was the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas from 1649 to 1959, has been a museum since then, and a World Heritage Site since 1994.

The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. The 5th Dalai Lama started its construction in 1645 after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa. It may overlie the remains of an earlier fortress called the White or Red Palace on the site, built by Songtsen Gampo in 637.

The building measures 400 metres (1,300 ft) east-west and 350 metres (1,150 ft) north-south, with sloping stone walls averaging 3 metres (9.8 ft) thick, and 5 metres (16 ft) thick at the base, and with copper poured into the foun...Read more

The Potala Palace is a dzong fortress in Lhasa, capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region in China. It was the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas from 1649 to 1959, has been a museum since then, and a World Heritage Site since 1994.

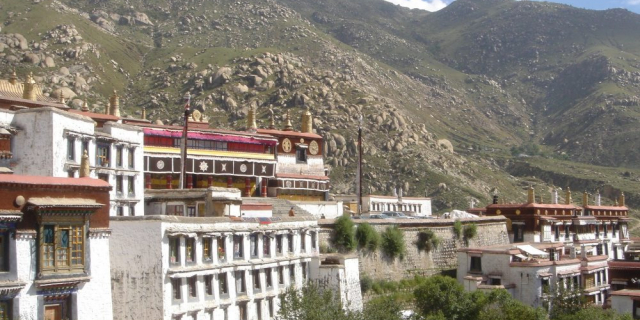

The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. The 5th Dalai Lama started its construction in 1645 after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa. It may overlie the remains of an earlier fortress called the White or Red Palace on the site, built by Songtsen Gampo in 637.

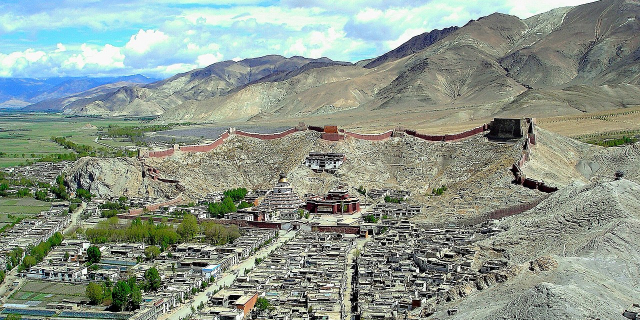

The building measures 400 metres (1,300 ft) east-west and 350 metres (1,150 ft) north-south, with sloping stone walls averaging 3 metres (9.8 ft) thick, and 5 metres (16 ft) thick at the base, and with copper poured into the foundations to help proof it against earthquakes. Thirteen storeys of buildings, containing over 1,000 rooms, 10,000 shrines and about 200,000 statues, soar 117 metres (384 ft) on top of Marpo Ri, the "Red Hill", rising more than 300 metres (980 ft) in total above the valley floor.

Tradition has it that the three main hills of Lhasa represent the "Three Protectors of Tibet". Chokpori, just to the south of the Potala, is the soul-mountain (Wylie: bla ri) of Vajrapani, Pongwari that of Manjusri, and Marpori, the hill on which the Potala stands, represents Avalokiteśvara.

The Sertreng ceremony photographed by Hugh Edward Richardson on 28 April 1949 with the double giant thangka banner on the white front of the palace.Potala Palace

The Sertreng ceremony photographed by Hugh Edward Richardson on 28 April 1949 with the double giant thangka banner on the white front of the palace.Potala Palace

The site on which the Potala Palace rises is built over a palace erected by Songtsen Gampo on the Red Hill.[1] The Potala contains two chapels on its northwest corner that conserve parts of the original building. One is the Phakpa Lhakhang, the other the Chogyel Drupuk, a recessed cavern identified as Songtsen Gampo's meditation cave.[2] Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started the construction of the modern Potala Palace in 1645[3] after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa.[4] The external structure was built in 3 years, while the interior, together with its furnishings, took 45 years to complete.[5] The Dalai Lama and his government moved into the Potrang Karpo ('White Palace') in 1649.[4] Construction lasted until 1694,[6] some twelve years after his death. The Potala was used as a winter palace by the Dalai Lama from that time. The Potrang Marpo ('Red Palace') was added between 1690 and 1694.[6]

The new palace got its name from a hill on Cape Comorin at the southern tip of India—a rocky point sacred to the bodhisattva of compassion, who is known as Avalokitesvara, or Chenrezi. The Tibetans themselves rarely speak of the sacred place as the "Potala", but rather as "Peak Potala" (Tse Potala), or most commonly as "the Peak".[7]

The palace was moderately damaged during the Tibetan uprising against the Chinese in 1959, when Chinese shells were launched into the palace's windows.[8] Before Chamdo Jampa Kalden was shot and taken prisoner by soldiers of the People's Liberation Army, he witnessed "Chinese cannon shells began landing on Norbulingka past midnight on 19 March 1959... The sky lit up as the Chinese shells hit the Chakpori Medical College and the Potala."[9] It also escaped damage during the Cultural Revolution in 1966 through the personal intervention of Zhou Enlai,[10][11] who was then the Premier of the People's Republic of China. According to Tibetan historian Tsering Woeser, the palace, which harboured "over 100,000 volumes of scriptures and historical documents" and "many store rooms for housing precious objects, handicrafts, paintings, wall hangings, statues, and ancient armour", "was almost robbed empty".[12]

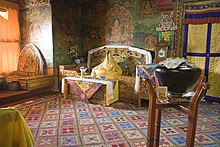

The former quarters of the Dalai Lama. The figure in the throne represents Tenzin Gyatso, the incumbent Dalai Lama

The former quarters of the Dalai Lama. The figure in the throne represents Tenzin Gyatso, the incumbent Dalai LamaThe Potala Palace was inscribed to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1994. In 2000 and 2001, Jokhang Temple and Norbulingka were added to the list as extensions to the sites. Rapid modernisation has been a concern for UNESCO, however, which expressed concern over the building of modern structures immediately around the palace which threaten the palace's unique atmosphere.[13] The Chinese government responded by enacting a rule barring the building of any structure taller than 21 metres in the area. UNESCO was also concerned over the materials used during the restoration of the palace, which commenced in 2002 at a cost of RMB180 million (US$22.5 million), although the palace's director, Qiangba Gesang, has clarified that only traditional materials and craftsmanship were used. The palace has also received restoration works between 1989 and 1994, costing RMB55 million (US$6.875 million).

The number of visitors to the palace was restricted to 1,600 a day, with opening hours reduced to six hours daily to avoid over-crowding from 1 May 2003. The palace was receiving an average of 1,500 a day prior to the introduction of the quota, sometimes peaking to over 5,000 in one day.[14] Visits to the structure's roof were banned after restoration efforts were completed in 2006 to avoid further structural damage.[15] Visitorship quotas were raised to 2,300 daily to accommodate a 30% increase in visitorship since the opening of the Qingzang railway into Lhasa on 1 July 2006, but the quota is often reached by mid-morning.[16] Opening hours were extended during the peak period in the months of July to September, where over 6,000 visitors would descend on the site.[17]

In February 2022, Tibetan pop star Tsewang Norbu set himself on fire in front of the Potala Palace and died. The Foreign Ministry of China has disputed this.[18]

Add new comment