Buddhism

Context of Buddhism

Buddhism ( BUU-dih-zəm, US also BOOD-), also known as Buddha Dharma, Bauddha and Dharmavinaya (transl. "doctrines and disciplines"), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in present-day North India as a śramaṇa–movement in the 5th century BCE, and gradually spread throughout much of Asia via the Silk Road. It is the world's fourth-largest religion, with over 520 million followers (Buddhists) who comprise seven percent of the global population.

The Buddha's central teachings emphasize the aim of attaining liberation from attachment or clinging to existence, which is said to be marked by impermanence (anitya), dissatisfaction/s...Read more

Buddhism ( BUU-dih-zəm, US also BOOD-), also known as Buddha Dharma, Bauddha and Dharmavinaya (transl. "doctrines and disciplines"), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in present-day North India as a śramaṇa–movement in the 5th century BCE, and gradually spread throughout much of Asia via the Silk Road. It is the world's fourth-largest religion, with over 520 million followers (Buddhists) who comprise seven percent of the global population.

The Buddha's central teachings emphasize the aim of attaining liberation from attachment or clinging to existence, which is said to be marked by impermanence (anitya), dissatisfaction/suffering (duḥkha), and the absence of lasting essence (anātman). He endorsed the Middle Way, a path of spiritual development that avoids both extreme asceticism and hedonism. A summary of this path is expressed in the Noble Eightfold Path, a cultivation of the mind through observance of meditation and Buddhist ethics. Other widely observed practices include: monasticism; "taking refuge" in the Buddha, the dharma, and the saṅgha; and the cultivation of perfections (pāramitā).

Buddhist schools vary in their interpretation of the paths to liberation (mārga) as well as the relative importance and 'canonicity' assigned to various Buddhist texts, and their specific teachings and practices. Two major extant branches of Buddhism are generally recognized by scholars: Theravāda (lit. 'School of the Elders') and Mahāyāna (lit. 'Great Vehicle'). The Theravada tradition emphasizes the attainment of nirvāṇa (lit. 'extinguishing') as a means of transcending the individual self and ending the cycle of death and rebirth (saṃsāra), while the Mahayana tradition emphasizes the Bodhisattva-ideal, in which one works for the liberation of all beings. The Buddhist canon is vast, with many different textual collections in different languages (such as Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, and Chinese).

The Theravāda branch has a widespread following in Sri Lanka as well as in Southeast Asia, namely Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. The Mahāyāna branch—which includes the traditions of Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren, Tiantai, Tendai, and Shingon—is predominantly practised in Nepal, Bhutan, China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. Additionally, Vajrayāna (lit. 'Indestructible Vehicle'), a body of teachings attributed to Indian adepts, may be viewed as a separate branch or tradition within Mahāyāna. Tibetan Buddhism, which preserves the Vajrayāna teachings of eighth-century India, is practised in the Himalayan states as well as in Mongolia and Russian Kalmykia. Historically, until the early 2nd millennium, Buddhism was widely practised in the Indian subcontinent; it also had a foothold to some extent elsewhere in Asia, namely Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and the Philippines.

More about Buddhism

Read moreRead lessHistorical roots

Read moreRead lessHistorical roots Mahākāśyapa meets an Ājīvika ascetic, one of the common Śramaṇa groups in ancient India

Mahākāśyapa meets an Ājīvika ascetic, one of the common Śramaṇa groups in ancient IndiaHistorically, the roots of Buddhism lie in the religious thought of Iron Age India around the middle of the first millennium BCE.[1] This was a period of great intellectual ferment and socio-cultural change known as the "Second urbanisation", marked by the growth of towns and trade, the composition of the Upanishads and the historical emergence of the Śramaṇa traditions.[2][3][note 1]

New ideas developed both in the Vedic tradition in the form of the Upanishads, and outside of the Vedic tradition through the Śramaṇa movements.[6][7][8] The term Śramaṇa refers to several Indian religious movements parallel to but separate from the historical Vedic religion, including Buddhism, Jainism and others such as Ājīvika.[9]

Several Śramaṇa movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century BCE (pre-Buddha, pre-Mahavira), and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy.[10] According to Martin Wilshire, the Śramaṇa tradition evolved in India over two phases, namely Paccekabuddha and Savaka phases, the former being the tradition of individual ascetic and the latter of disciples, and that Buddhism and Jainism ultimately emerged from these.[11] Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical ascetic groups shared and used several similar ideas,[12] but the Śramaṇa traditions also drew upon already established Brahmanical concepts and philosophical roots, states Wiltshire, to formulate their own doctrines.[10][13] Brahmanical motifs can be found in the oldest Buddhist texts, using them to introduce and explain Buddhist ideas.[14] For example, prior to Buddhist developments, the Brahmanical tradition internalised and variously reinterpreted the three Vedic sacrificial fires as concepts such as Truth, Rite, Tranquility or Restraint.[15] Buddhist texts also refer to the three Vedic sacrificial fires, reinterpreting and explaining them as ethical conduct.[16]

The Śramaṇa religions challenged and broke with the Brahmanic tradition on core assumptions such as Atman (soul, self), Brahman, the nature of afterlife, and they rejected the authority of the Vedas and Upanishads.[17][18][19] Buddhism was one among several Indian religions that did so.[19]

Early buddhist positions in the Theravada tradition had not established any deities, but were epistemologically cautious rather than directly atheist. Later buddhist traditions were more influenced by the critique of deities within Hinduism and therefore more committed to a strongly atheist stance. These developments were historic and epistemological as documented in verses from Śāntideva's Bodhicaryāvatāra, and supplemented by reference to suttas and jātakas from the Pali canon.[20]

Indian Buddhism Ajanta Caves, Cave 10, a first period type chaitya worship hall with stupa but no idols

Ajanta Caves, Cave 10, a first period type chaitya worship hall with stupa but no idolsThe history of Indian Buddhism may be divided into five periods:[21] Early Buddhism (occasionally called pre-sectarian Buddhism), Nikaya Buddhism or Sectarian Buddhism: The period of the early Buddhist schools, Early Mahayana Buddhism, Late Mahayana, and the era of Vajrayana or the "Tantric Age".

Pre-sectarian BuddhismAccording to Lambert Schmithausen Pre-sectarian Buddhism is "the canonical period prior to the development of different schools with their different positions."[22]

The early Buddhist Texts include the four principal Pali Nikāyas [note 2] (and their parallel Agamas found in the Chinese canon) together with the main body of monastic rules, which survive in the various versions of the patimokkha.[23][24][25] However, these texts were revised over time, and it is unclear what constitutes the earliest layer of Buddhist teachings. One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest extant versions of the Theravadin Pāli Canon and other texts.[note 3] The reliability of the early sources, and the possibility to draw out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute.[28] According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[26][note 4]

According to Schmithausen, three positions held by scholars of Buddhism can be distinguished:[34]

"Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials;"[note 5] "Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of earliest Buddhism;"[note 6] "Cautious optimism in this respect."[note 7]The Core teachingsAccording to Mitchell, certain basic teachings appear in many places throughout the early texts, which has led most scholars to conclude that Gautama Buddha must have taught something similar to the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, Nirvana, the three marks of existence, the five aggregates, dependent origination, karma and rebirth.[40]

According to N. Ross Reat, all of these doctrines are shared by the Theravada Pali texts and the Mahasamghika school's Śālistamba Sūtra.[41] A recent study by Bhikkhu Analayo concludes that the Theravada Majjhima Nikaya and Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contain mostly the same major doctrines.[42] Richard Salomon, in his study of the Gandharan texts (which are the earliest manuscripts containing early discourses), has confirmed that their teachings are "consistent with non-Mahayana Buddhism, which survives today in the Theravada school of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, but which in ancient times was represented by eighteen separate schools."[43]

However, some scholars argue that critical analysis reveals discrepancies among the various doctrines found in these early texts, which point to alternative possibilities for early Buddhism.[44][45][46] The authenticity of certain teachings and doctrines have been questioned. For example, some scholars think that karma was not central to the teaching of the historical Buddha, while other disagree with this position.[47][48] Likewise, there is scholarly disagreement on whether insight was seen as liberating in early Buddhism or whether it was a later addition to the practice of the four jhānas.[29][49][50] Scholars such as Bronkhorst also think that the four noble truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of "liberating insight".[51] According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term "the middle way".[30] In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.[30]

Ashokan Era and the early schools Sanchi Stupa No. 3, near Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, India

Sanchi Stupa No. 3, near Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh, IndiaAccording to numerous Buddhist scriptures, soon after the parinirvāṇa (from Sanskrit: "highest extinguishment") of Gautama Buddha, the first Buddhist council was held to collectively recite the teachings to ensure that no errors occurred in oral transmission. Many modern scholars question the historicity of this event.[52] However, Richard Gombrich states that the monastic assembly recitations of the Buddha's teaching likely began during Buddha's lifetime, and they served a similar role of codifying the teachings.[53]

The so called Second Buddhist council resulted in the first schism in the Sangha. Modern scholars believe that this was probably caused when a group of reformists called Sthaviras ("elders") sought to modify the Vinaya (monastic rule), and this caused a split with the conservatives who rejected this change, they were called Mahāsāṃghikas.[54][55] While most scholars accept that this happened at some point, there is no agreement on the dating, especially if it dates to before or after the reign of Ashoka.[56]

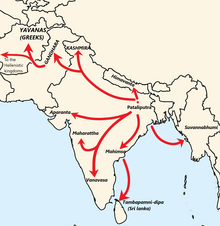

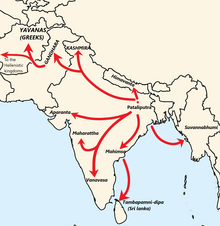

Map of the Buddhist missions during the reign of Ashoka according to the Edicts of Ashoka

Map of the Buddhist missions during the reign of Ashoka according to the Edicts of AshokaBuddhism may have spread only slowly throughout India until the time of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE), who was a public supporter of the religion. The support of Aśoka and his descendants led to the construction of more stūpas (such as at Sanchi and Bharhut), temples (such as the Mahabodhi Temple) and to its spread throughout the Maurya Empire and into neighbouring lands such as Central Asia and to the island of Sri Lanka.

During and after the Mauryan period (322–180 BCE), the Sthavira community gave rise to several schools, one of which was the Theravada school which tended to congregate in the south and another which was the Sarvāstivāda school, which was mainly in north India. Likewise, the Mahāsāṃghika groups also eventually split into different Sanghas. Originally, these schisms were caused by disputes over monastic disciplinary codes of various fraternities, but eventually, by about 100 CE if not earlier, schisms were being caused by doctrinal disagreements too.[57]

Following (or leading up to) the schisms, each Saṅgha started to accumulate their own version of Tripiṭaka (triple basket of texts).[58][59] In their Tripiṭaka, each school included the Suttas of the Buddha, a Vinaya basket (disciplinary code) and some schools also added an Abhidharma basket which were texts on detailed scholastic classification, summary and interpretation of the Suttas.[58][60] The doctrine details in the Abhidharmas of various Buddhist schools differ significantly, and these were composed starting about the third century BCE and through the 1st millennium CE.[61][62][63]

Post-Ashokan expansion Extent of Buddhism and trade routes in the 1st century CE

Extent of Buddhism and trade routes in the 1st century CEAccording to the edicts of Aśoka, the Mauryan emperor sent emissaries to various countries west of India to spread "Dharma", particularly in eastern provinces of the neighbouring Seleucid Empire, and even farther to Hellenistic kingdoms of the Mediterranean. It is a matter of disagreement among scholars whether or not these emissaries were accompanied by Buddhist missionaries.[64]

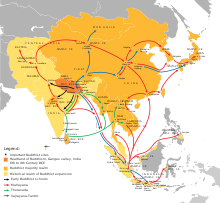

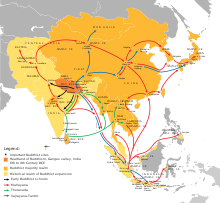

Buddhist expansion throughout Asia

Buddhist expansion throughout AsiaIn central and west Asia, Buddhist influence grew, through Greek-speaking Buddhist monarchs and ancient Asian trade routes, a phenomenon known as Greco-Buddhism. An example of this is evidenced in Chinese and Pali Buddhist records, such as Milindapanha and the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhāra. The Milindapanha describes a conversation between a Buddhist monk and the 2nd-century BCE Greek king Menander, after which Menander abdicates and himself goes into monastic life in the pursuit of nirvana.[65][66] Some scholars have questioned the Milindapanha version, expressing doubts whether Menander was Buddhist or just favourably disposed to Buddhist monks.[67]

The Kushan empire (30–375 CE) came to control the Silk Road trade through Central and South Asia, which brought them to interact with Gandharan Buddhism and the Buddhist institutions of these regions. The Kushans patronised Buddhism throughout their lands, and many Buddhist centers were built or renovated (the Sarvastivada school was particularly favored), especially by Emperor Kanishka (128–151 CE).[68][69] Kushan support helped Buddhism to expand into a world religion through their trade routes.[70] Buddhism spread to Khotan, the Tarim Basin, and China, eventually to other parts of the far east.[69] Some of the earliest written documents of the Buddhist faith are the Gandharan Buddhist texts, dating from about the 1st century CE, and connected to the Dharmaguptaka school.[71][72][73]

The Islamic conquest of the Iranian Plateau in the 7th-century, followed by the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan and the later establishment of the Ghaznavid kingdom with Islam as the state religion in Central Asia between the 10th- and 12th-century led to the decline and disappearance of Buddhism from most of these regions.[74]

Mahāyāna BuddhismA Buddhist triad depicting, left to right, a Kushan, the future buddha Maitreya, Gautama Buddha, the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, and a monk. Second–third century. Guimet MuseumThe origins of Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") Buddhism are not well understood and there are various competing theories about how and where this movement arose. Theories include the idea that it began as various groups venerating certain texts or that it arose as a strict forest ascetic movement.[75]

The first Mahāyāna works were written sometime between the 1st century BCE and the 2nd century CE.[76][75] Much of the early extant evidence for the origins of Mahāyāna comes from early Chinese translations of Mahāyāna texts, mainly those of Lokakṣema. (2nd century CE).[note 8] Some scholars have traditionally considered the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the first versions of the Prajnaparamita series, along with texts concerning Akṣobhya, which were probably composed in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.[78][note 9]

There is no evidence that Mahāyāna ever referred to a separate formal school or sect of Buddhism, with a separate monastic code (Vinaya), but rather that it existed as a certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for bodhisattvas.[80][81] Records written by Chinese monks visiting India indicate that both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks could be found in the same monasteries, with the difference that Mahāyāna monks worshipped figures of Bodhisattvas, while non-Mahayana monks did not.[82]

Site of Nalanda University, a great center of Mahāyāna thought

Site of Nalanda University, a great center of Mahāyāna thoughtMahāyāna initially seems to have remained a small minority movement that was in tension with other Buddhist groups, struggling for wider acceptance.[83] However, during the fifth and sixth centuries CE, there seems to have been a rapid growth of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which is shown by a large increase in epigraphic and manuscript evidence in this period. However, it still remained a minority in comparison to other Buddhist schools.[84]

Mahāyāna Buddhist institutions continued to grow in influence during the following centuries, with large monastic university complexes such as Nalanda (established by the 5th-century CE Gupta emperor, Kumaragupta I) and Vikramashila (established under Dharmapala c. 783 to 820) becoming quite powerful and influential. During this period of Late Mahāyāna, four major types of thought developed: Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, Buddha-nature (Tathāgatagarbha), and the epistemological tradition of Dignaga and Dharmakirti.[85] According to Dan Lusthaus, Mādhyamaka and Yogācāra have a great deal in common, and the commonality stems from early Buddhism.[86]

Late Indian Buddhism and Tantra Vajrayana adopted deities such as Bhairava, known as Yamantaka in Tibetan Buddhism.

Vajrayana adopted deities such as Bhairava, known as Yamantaka in Tibetan Buddhism.During the Gupta period (4th–6th centuries) and the empire of Harṣavardana (c. 590–647 CE), Buddhism continued to be influential in India, and large Buddhist learning institutions such as Nalanda and Valabahi Universities were at their peak.[87] Buddhism also flourished under the support of the Pāla Empire (8th–12th centuries). Under the Guptas and Palas, Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana developed and rose to prominence. It promoted new practices such as the use of mantras, dharanis, mudras, mandalas and the visualization of deities and Buddhas and developed a new class of literature, the Buddhist Tantras. This new esoteric form of Buddhism can be traced back to groups of wandering yogi magicians called mahasiddhas.[88][89]

The question of the origins of early Vajrayana has been taken up by various scholars. David Seyfort Ruegg has suggested that Buddhist tantra employed various elements of a "pan-Indian religious substrate" which is not specifically Buddhist, Shaiva or Vaishnava.[90]

According to Indologist Alexis Sanderson, various classes of Vajrayana literature developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism. Sanderson has argued that Buddhist tantras can be shown to have borrowed practices, terms, rituals and more form Shaiva tantras. He argues that Buddhist texts even directly copied various Shaiva tantras, especially the Bhairava Vidyapitha tantras.[91][92] Ronald M. Davidson meanwhile, argues that Sanderson's claims for direct influence from Shaiva Vidyapitha texts are problematic because "the chronology of the Vidyapitha tantras is by no means so well established"[93] and that the Shaiva tradition also appropriated non-Hindu deities, texts and traditions. Thus while "there can be no question that the Buddhist tantras were heavily influenced by Kapalika and other Saiva movements" argues Davidson, "the influence was apparently mutual."[94]

Already during this later era, Buddhism was losing state support in other regions of India, including the lands of the Karkotas, the Pratiharas, the Rashtrakutas, the Pandyas and the Pallavas. This loss of support in favor of Hindu faiths like Vaishnavism and Shaivism, is the beginning of the long and complex period of the Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent.[95] The Islamic invasions and conquest of India (10th to 12th century), further damaged and destroyed many Buddhist institutions, leading to its eventual near disappearance from India by the 1200s.[96]

Spread to East and Southeast AsiaAngkor Thom build by Khmer King Jayavarman VII (c. 1120–1218)The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism to China is most commonly thought to have started in the late 2nd or the 1st century CE, though the literary sources are all open to question.[97][note 10] The first documented translation efforts by foreign Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE, probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin.[99]

The first documented Buddhist texts translated into Chinese are those of the Parthian An Shigao (148–180 CE).[100] The first known Mahāyāna scriptural texts are translations into Chinese by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema in Luoyang, between 178 and 189 CE.[101] From China, Buddhism was introduced into its neighbours Korea (4th century), Japan (6th–7th centuries), and Vietnam (c. 1st–2nd centuries).[102][103]

During the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907), Chinese Esoteric Buddhism was introduced from India and Chan Buddhism (Zen) became a major religion.[104][105] Chan continued to grow in the Song dynasty (960–1279) and it was during this era that it strongly influenced Korean Buddhism and Japanese Buddhism.[106] Pure Land Buddhism also became popular during this period and was often practised together with Chan.[107] It was also during the Song that the entire Chinese canon was printed using over 130,000 wooden printing blocks.[108]

During the Indian period of Esoteric Buddhism (from the 8th century onwards), Buddhism spread from India to Tibet and Mongolia. Johannes Bronkhorst states that the esoteric form was attractive because it allowed both a secluded monastic community as well as the social rites and rituals important to laypersons and to kings for the maintenance of a political state during succession and wars to resist invasion.[109] During the Middle Ages, Buddhism slowly declined in India,[110] while it vanished from Persia and Central Asia as Islam became the state religion.[111][112]

The Theravada school arrived in Sri Lanka sometime in the 3rd century BCE. Sri Lanka became a base for its later spread to Southeast Asia after the 5th century CE (Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia and coastal Vietnam).[113][114] Theravada Buddhism was the dominant religion in Burma during the Mon Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287–1552).[115] It also became dominant in the Khmer Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries and in the Thai Sukhothai Kingdom during the reign of Ram Khamhaeng (1237/1247–1298).[116][117]

^ Gethin (2008), p. xv. ^ Abraham Eraly (2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. Penguin Books. pp. 538, 571. ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4. ^ Gombrich (1988), pp. 26–41. ^ a b Queen, Christopher. "Introduction: The Shapes and Sources of Engaged Buddhism". In Queen & King (1996), pp. 17–18. ^ Gombrich (1988), pp. 30–31. ^ Hajime Nakamura (1983). A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 102–104, 264–269, 294–295. ISBN 978-81-208-0651-1.; Quote: "But the Upanishadic ultimate meaning of the Vedas, was, from the viewpoint of the Vedic canon in general, clearly a new idea.."; p. 95: The [oldest] Upanishads in particular were part of the Vedic corpus (...) When these various new ideas were brought together and edited, they were added on to the already existing Vedic..."; p. 294: "When early Jainism came into existence, various ideas mentioned in the extant older Upanishads were current,....". ^ Klaus G. Witz (1998). The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–2, 23. ISBN 978-81-208-1573-5.; Quote: "In the Aranyakas therefore, thought and inner spiritual awareness started to separate subtler, deeper aspects from the context of ritual performance and myth with which they had been united up to then. This process was then carried further and brought to completion in the Upanishads. (...) The knowledge and attainment of the Highest Goal had been there from the Vedic times. But in the Upanishads inner awareness, aided by major intellectual breakthroughs, arrived at a language in which Highest Goal could be dealt with directly, independent of ritual and sacred lore".

Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle (1994). The Origin and Development of Early Indian Contemplative Practices. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 58 with footnote 148, 22–29, 87–103, for Upanishads–Buddhist Sutta discussion see 65–72. ISBN 978-3-447-03479-1. ^ Patrick Olivelle (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–5, 68–71. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7.;

Christoph Wulf (2016). Exploring Alterity in a Globalized World. Routledge. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-1-317-33113-1.; Quote: "But he [Bronkhorst] talks about the simultaneous emergence of a Vedic and a non-Vedic asceticism. (...) [On Olivelle] Thus, the challenge for old Vedic views consisted of a new theology, written down in the early Upanishads like the Brhadaranyaka and the Mundaka Upanishad. The new set of ideas contained the...." ^ AL Basham (1951), History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas – a Vanished Indian Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1204-8, pp. 94–103 ^ a b Reginald Ray (1999), Buddhist Saints in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513483-4, pp. 237–240, 247–249 ^ Martin Wiltshire (1990), Ascetic Figures Before and in Early Buddhism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-009896-9, p. 293 ^ Samuel (2010), pp. 123–125. ^ Martin Wiltshire (1990), Ascetic Figures Before and in Early Buddhism, De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-009896-9, pp. 226–227 ^ Shults (2014), p. 126. ^ Shults (2014), p. 127. ^ Shults (2014), pp. 125–129. ^ P. Billimoria (1988), Śabdapramāṇa: Word and Knowledge, Studies of Classical India Volume 10, Springer, ISBN 978-94-010-7810-8, pp. 1–30 ^ Jaini (2001), pp. 47–48. ^ a b Mark Siderits (2007). Buddhism as Philosophy: An Introduction. Ashgate. p. 16 with footnote 3. ISBN 978-0-7546-5369-1. ^ Skilton A (01 October 2013). Buddhism pg. 337-350. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199644650.013.004. Retrieved 10 April 2023. ^ Hirakawa (1993), p. 7. ^ Schmithausen (1987) "Part I: Earliest Buddhism," Panels of the VIIth World Sanskrit Conference Vol. II: Earliest Buddhism and Madhyamaka, ed. David Seyfort Ruegg and Lambert Schmithausen, Leiden: Kern Institute, pp. 1–4. ^ Sujato & Brahmali (2015), p. 39–41. ^ Gethin (2008), p. xviii. ^ Harvey (1998), p. 3. ^ a b Vetter (1988), p. ix. ^ a b Warder (2000). ^ Vetter (1988), pp. xxi–xxxvii. ^ a b Schmithausen (1981). ^ a b c Vetter (1988). ^ Norman (1992). ^ a b Gombrich (1997). ^ Bronkhorst (1993). ^ a b Bronkhorst (1993), p. vii. ^ Warder (2000), inside flap. ^ Bronkhorst (1993), p. viii. ^ Davidson (2003), p. 147. ^ a b Jong (1993), p. 25. ^ Lopez (1995), p. 4. ^ Mitchell (2002), p. 34. ^ Reat, Noble Ross. "The Historical Buddha and his Teachings". In: Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophy. Ed. by Potter, Karl H. Vol. VII: Abhidharma Buddhism to 150 AD. Motilal Banarsidass, 1996, pp. 28, 33, 37, 41, 43, 48. ^ Analayo (2011). A Comparative Study of the Majjhima-nikāya. Dharma Drum Academic Publisher. p. 891. ^ Salomon, Richard (20 January 2020). "How the Gandharan Manuscripts Change Buddhist History". Lion's Roar. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020. ^ Skorupski (1990), p. 5. ^ Bronkhorst (1998), pp. 4, 11. ^ Schopen (2002). ^ Matthews (1986), p. 124. ^ Bronkhorst (1998), p. 14. ^ Bronkhorst (1993), pp. 77–78, Section 8.4.3. ^ Vetter (1988), p. 5, Quote: [T]hey do not teach that one is released by knowing the four noble truths, but by practising the fourth noble truth, the eightfold path, which culminates in right samadhi. ^ Bronkhorst (1993), p. 107. ^ Harvey (2013), pp. 88–90. ^ Williams (2005), pp. 175–176. ^ Harvey (2013), pp. 89–90. ^ Skilton, Andrew. A Concise History of Buddhism. 2004. pp. 49, 64 ^ Sujato, Bhante (2012), Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools, Santipada, ISBN 978-1-921842-08-5 ^ Harvey (1998), pp. 74–75. ^ a b Tipitaka Archived 27 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica (2015) ^ Barbara Crandall (2012). Gender and Religion: The Dark Side of Scripture (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-4411-4871-1. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2016. ^ Harvey (2013), pp. 90–91. ^ Harvey (2013), pp. 90–93. ^ "Abhidhamma Pitaka". Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008. ^ Keown & Prebish (2004), p. 485. ^ Gombrich (2005a), p. 135. ^ Trainor (2004), pp. 103, 119. ^ Jason Neelis (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Brill Academic. pp. 102–106. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2016. ^ Ann Heirman; Stephan Peter Bumbacher (2007). The Spread of Buddhism. Brill Academic. pp. 139–142. ISBN 978-90-04-15830-6. ^ Kurt A. Behrendt, The Buddhist architecture of Gandhara, Handbuch der Orientalistik Brill, 2004, p. 13 ^ a b Heirman, Ann; Bumbacher, Stephan Peter (editors). The Spread of Buddhism, Brill, p. 57 ^ Xinru Liu (2010). The Silk Road in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-533810-2. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2018. ^ Warder2000, p. 278. ^ "The Discovery of 'the Oldest Buddhist Manuscripts'" Review article by Enomoto Fumio. The Eastern Buddhist, Vol NS32 Issue I, 2000, p. 161 ^ Bhikkhu Sujato. "Abstract: Sects & Sectarianism. The Origin of the three existing Vinaya lineages: Theravada, Dharmaguptaka, and Mulasarvastivada". Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2017. ^ Kudara, Kogi (2002). "A Rough Sketch of Central Asian Buddhism". Pacific World: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies. 3 (4): 93–107. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018. ^ a b Drewes, David, Early Indian Mahayana Buddhism I: Recent Scholarship, Religion Compass 4/2 (2010): 55–65, doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00195.x ^ Hirakawa (1993), p. 252. ^ Buswell (2004), p. 492. ^ Hirakawa (1993), pp. 252–253, 263, 268. ^ Warder (2000), p. 335. ^ Nattier (2003), pp. 193–194. ^ Williams (2008), pp. 4–5. ^ Williams (2000), p. 97. ^ Walser, Joseph, Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture, Columbia University Press, 2005, p. 18. ^ Walser, Joseph, Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture, Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 29-34. ^ Hirakawa (1993), pp. 8–9. ^ Lusthaus (2002), pp. 236–237. ^ Warder (2000), p. 442. ^ Ray, Reginald A (2000) Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism. ^ Davidson, Ronald M.,(2002). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, Columbia University Press, p. 228, 234. ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 171. ^ Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, pp. 23, 124, 129-31. ^ Sanderson, Alexis; Vajrayana:, Origin and Function, 1994 ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 204. ^ Davidson, Ronald M. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement, p. 217. ^ Omvedt, Gail (2003). "Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste", p. 172. ^ Collins (2000), pp. 184–185. ^ Zürcher (1972), pp. 22–27. ^ Hill (2009), pp. 30–31. ^ Zürcher (1972), p. 23. ^ Zürcher, Erik. 2007 (1959). The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. 3rd ed. Leiden: Brill. pp. 32–34 ^ Williams (2008), p. 30. ^ Dykstra, Yoshiko Kurata; De Bary, William Theodore (2001). Sources of Japanese tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-231-12138-5. ^ Nguyen Tai Thu. The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. 2008. ^ McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen, The University Press Group Ltd, pp. 13, 18 ^ Orzech, Charles D. (general editor) (2011). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Brill. p. 4 ^ McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen, The University Press Group Ltd, pp. 13, 19–21 ^ Heng-Ching Shih (1987). Yung-Ming's Syncretism of Pure Land and Chan, The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 10 (1), p. 117 ^ Harvey (2013), p. 223. ^ Bronkhorst (2011), pp. 242–246. ^ Andrew Powell (1989). Living Buddhism. University of California Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-520-20410-2. ^ Lars Fogelin (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–11, 218, 229–230. ISBN 978-0-19-994823-9. ^ Sheila Canby (1993). "Depictions of Buddha Sakyamuni in the Jami al-Tavarikh and the Majma al-Tavarikh". Muqarnas. 10: 299–310. doi:10.2307/1523195. JSTOR 1523195. ^ John Guy (2014). Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 9–11, 14–15, 19–20. ISBN 978-1-58839-524-5. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2016. ^ Skilling (1997). ^ Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps – Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6. pp. 64–65 ^ Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1. ^ Gyallay-Pap, Peter. "Notes of the Rebirth of Khmer Buddhism," Radical Conservativism.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=subnote> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=subnote}} template (see the help page).