Florence

Context of Florence

Florence ( FLORR-ənss; Italian: Firenze [fiˈrɛntse] (listen)) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.

Florence was a centre of medieval European trade and finance and one of the wealthiest cities of that era. It is considered by many academics to have been the birthplace of the Renaissance, becoming a major artistic, cultural, commercial, political, economic and financial center. During this time, Florence rose to a position of enormous influence in Italy, Europe, and beyond. Its turbulent political history includes periods of rule by...Read more

Florence ( FLORR-ənss; Italian: Firenze [fiˈrɛntse] (listen)) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.

Florence was a centre of medieval European trade and finance and one of the wealthiest cities of that era. It is considered by many academics to have been the birthplace of the Renaissance, becoming a major artistic, cultural, commercial, political, economic and financial center. During this time, Florence rose to a position of enormous influence in Italy, Europe, and beyond. Its turbulent political history includes periods of rule by the powerful Medici family and numerous religious and republican revolutions. From 1865 to 1871 the city served as the capital of the Kingdom of Italy. The Florentine dialect forms the base of Standard Italian and it became the language of culture throughout Italy due to the prestige of the masterpieces by Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini.

The city attracts millions of tourists each year, and UNESCO declared the Historic Centre of Florence a World Heritage Site in 1982. The city is noted for its culture, Renaissance art and architecture and monuments. The city also contains numerous museums and art galleries, such as the Uffizi Gallery and the Palazzo Pitti, and still exerts an influence in the fields of art, culture and politics. Due to Florence's artistic and architectural heritage, Forbes ranked it as the most beautiful city in the world in 2010.

Florence plays an important role in Italian fashion, and is ranked in the top 15 fashion capitals of the world by Global Language Monitor; furthermore, it is a major national economic centre, as well as a tourist and industrial hub.

More about Florence

- Population 253565

- Area 102

- Read lessTimeline of Florence

Historical affiliationsRoman Republic, 59–27 BC

Roman Empire, 27 BC–AD 285

Western Roman Empire, 285–476

Kingdom of Odoacer, 476–493

Ostrogothic Kingdom, 493–553

Eastern Roman Empire, 553–568

Lombard Kingdom, 570–773

Carolingian Empire, 774–797

Regnum Italiae, 797–1001

March of Tuscany, 1002–1115 Republic of Florence, 1115–1532

Republic of Florence, 1115–1532  Duchy of Florence, 1532–1569

Duchy of Florence, 1532–1569  Grand Duchy of Tuscany, 1569–1801

Grand Duchy of Tuscany, 1569–1801  Kingdom of Etruria, 1801–1807

Kingdom of Etruria, 1801–1807  First French Empire, 1807–1815

First French Empire, 1807–1815  Grand Duchy of Tuscany, 1815–1859

Grand Duchy of Tuscany, 1815–1859  United Provinces of Central Italy, 1859–1860

United Provinces of Central Italy, 1859–1860  Kingdom of Italy, 1861–1943

Kingdom of Italy, 1861–1943  Italian Social Republic, 1943–1945

Italian Social Republic, 1943–1945  Italy, 1946–present

Italy, 1946–present

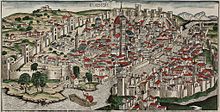

View of Florence by Hartmann Schedel, published in 1493

View of Florence by Hartmann Schedel, published in 1493Florence originated as a Roman city, and later, after a long period as a flourishing trading and banking medieval commune, it was the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance. It was politically, economically, and culturally one of the most important cities in Europe and the world from the 14th to 16th centuries.[1]

The language spoken in the city during the 14th century came to be accepted as the model for what would become the Italian language. Thanks especially to the works of the Tuscans Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, the Florentine dialect, above all the local dialects, was adopted as the basis for a national literary language.[citation needed]

Starting from the late Middle Ages, Florentine money—in the form of the gold florin—financed the development of industry all over Europe, from Britain to Bruges, to Lyon and Hungary. Florentine bankers financed the English kings during the Hundred Years' War. They similarly financed the papacy, including the construction of their provisional capital of Avignon and, after their return to Rome, the reconstruction and Renaissance embellishment of Rome.

Florence was home to the Medici, one of European history's most important noble families. Lorenzo de' Medici was considered a political and cultural mastermind of Italy in the late 15th century. Two members of the family were popes in the early 16th century: Leo X and Clement VII. Catherine de Medici married King Henry II of France and, after his death in 1559, reigned as regent in France. Marie de' Medici married Henry IV of France and gave birth to the future King Louis XIII. The Medici reigned as Grand Dukes of Tuscany, starting with Cosimo I de' Medici in 1569 and ending with the death of Gian Gastone de' Medici in 1737.

The Kingdom of Italy, which was established in 1861, moved its capital from Turin to Florence in 1865, although the capital was moved to Rome in 1871.

Roman originsFlorence was established by the Romans in 59 BC as a colony for veteran soldiers and was built in the style of an army camp.[2] Situated along the Via Cassia, the main route between Rome and the north, and within the fertile valley of the Arno, the settlement quickly became an important commercial centre and in AD 285 became the capital of the Tuscia region.

Early Middle Ages The Goth King Totila razes the walls of Florence during the Gothic War: illumination from the Chigi manuscript of Villani's Cronica.

The Goth King Totila razes the walls of Florence during the Gothic War: illumination from the Chigi manuscript of Villani's Cronica.In centuries to come, the city experienced turbulent alternate periods of Ostrogoth and Byzantine rule, during which the city was fought over, helping to cause the population to fall to as low as 1,000 people.[3] Peace returned under Lombard rule in the 6th century and Florence was in turn conquered by Charlemagne in 774 becoming part of the March of Tuscany centred on Lucca. The population began to grow again and commerce prospered.

Second millennium The Basilica di San Miniato al Monte

The Basilica di San Miniato al MonteMargrave Hugo chose Florence as his residency instead of Lucca around 1000 AD. The Golden Age of Florentine art began around this time. In 1100, Florence was a "commune", meaning a city-state. The city's primary resource was the Arno river, providing power and access for the industry (mainly textile industry), and access to the Mediterranean sea for international trade, helping the growth of an industrious merchant community. The Florentine merchant banking skills became recognised in Europe after they brought decisive financial innovation (e.g. bills of exchange,[4] double-entry bookkeeping system) to medieval fairs. This period also saw the eclipse of Florence's formerly powerful rival Pisa.[5] The growing power of the merchant elite culminated in an anti-aristocratic uprising, led by Giano della Bella, resulting in the Ordinances of Justice[6] which entrenched the power of the elite guilds until the end of the Republic.

Middle Ages and Renaissance Rise of the Medici Leonardo da Vinci statue outside the Uffizi Gallery

Leonardo da Vinci statue outside the Uffizi GalleryAt the height of demographic expansion around 1325, the urban population may have been as great as 120,000, and the rural population around the city was probably close to 300,000.[7] The Black Death of 1348 reduced it by over half,[8][9] about 25,000 are said to have been supported by the city's wool industry: in 1345 Florence was the scene of an attempted strike by wool combers (ciompi), who in 1378 rose up in a brief revolt against oligarchic rule in the Revolt of the Ciompi. After their suppression, Florence came under the sway (1382–1434) of the Albizzi family, who became bitter rivals of the Medici.

In the 15th century, Florence was among the largest cities in Europe, with a population of 60,000, and was considered rich and economically successful.[10] Cosimo de' Medici was the first Medici family member to essentially control the city from behind the scenes. Although the city was technically a democracy of sorts, his power came from a vast patronage network along with his alliance to the new immigrants, the gente nuova (new people). The fact that the Medici were bankers to the pope also contributed to their ascendancy. Cosimo was succeeded by his son Piero, who was, soon after, succeeded by Cosimo's grandson, Lorenzo in 1469. Lorenzo was a great patron of the arts, commissioning works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli. Lorenzo was an accomplished poet and musician and brought composers and singers to Florence, including Alexander Agricola, Johannes Ghiselin, and Heinrich Isaac. By contemporary Florentines (and since), he was known as "Lorenzo the Magnificent" (Lorenzo il Magnifico).

Following Lorenzo de' Medici's death in 1492, he was succeeded by his son Piero II. When the French king Charles VIII invaded northern Italy, Piero II chose to resist his army. But when he realised the size of the French army at the gates of Pisa, he had to accept the humiliating conditions of the French king. These made the Florentines rebel, and they expelled Piero II. With his exile in 1494, the first period of Medici rule ended with the restoration of a republican government.

Savonarola, Machiavelli, and the Medici popes Girolamo Savonarola being burnt at the stake in 1498. The brooding Palazzo Vecchio is at centre right.

Girolamo Savonarola being burnt at the stake in 1498. The brooding Palazzo Vecchio is at centre right.During this period, the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola had become prior of the San Marco monastery in 1490. He was famed for his penitential sermons, lambasting what he viewed as widespread immorality and attachment to material riches. He praised the exile of the Medici as the work of God, punishing them for their decadence. He seized the opportunity to carry through political reforms leading to a more democratic rule. But when Savonarola publicly accused Pope Alexander VI of corruption, he was banned from speaking in public. When he broke this ban, he was excommunicated. The Florentines, tired of his teachings, turned against him and arrested him. He was convicted as a heretic, hanged and burned at the stake on the Piazza della Signoria on 23 May 1498. His ashes were dispersed in the Arno river.[11]

Another Florentine of this period was Niccolò Machiavelli, whose prescriptions for Florence's regeneration under strong leadership have often been seen as a legitimization of political expediency and even malpractice. Machiavelli was a political thinker, renowned for his political handbook The Prince, which is about ruling and exercising power. Commissioned by the Medici, Machiavelli also wrote the Florentine Histories, the history of the city.

In 1512, the Medici retook control of Florence with the help of Spanish and Papal troops.[12] They were led by two cousins, Giovanni and Giulio de' Medici, both of whom would later become Popes of the Catholic Church, (Leo X and Clement VII, respectively). Both were generous patrons of the arts, commissioning works like Michelangelo's Laurentian Library and Medici Chapel in Florence, to name just two.[13][14] Their reigns coincided with political upheaval in Italy, and thus in 1527, Florentines drove out the Medici for a second time and re-established a theocratic republic on 16 May 1527, (Jesus Christ was named King of Florence).[15] The Medici returned to power in Florence in 1530, with the armies of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and the blessings of Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici).

Florence officially became a monarchy in 1531, when Emperor Charles and Pope Clement named Alessandro de Medici as Duke of the Florentine Republic. The Medici's monarchy would last over two centuries. Alessandro's successor, Cosimo I de Medici, was named Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1569; in all Tuscany, only the Republic of Lucca (later a Duchy) and the Principality of Piombino were independent from Florence.

18th and 19th centuries Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor and his family. Leopold was, from 1765 to 1790, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor and his family. Leopold was, from 1765 to 1790, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.The extinction of the Medici dynasty and the accession in 1737 of Francis Stephen, duke of Lorraine and husband of Maria Theresa of Austria, led to Tuscany's temporary inclusion in the territories of the Austrian crown. It became a secundogeniture of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty, who were deposed for the House of Bourbon-Parma in 1801. From 1801 to 1807 Florence was the capital of the Napoleonic client state Kingdom of Etruria. The Bourbon-Parma were deposed in December 1807 when Tuscany was annexed by France. Florence was the prefecture of the French département of Arno from 1808 to the fall of Napoleon in 1814. The Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty was restored on the throne of Tuscany at the Congress of Vienna but finally deposed in 1859. Tuscany became a region of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

Florence replaced Turin as Italy's capital in 1865 and, in an effort to modernise the city, the old market in the Piazza del Mercato Vecchio and many medieval houses were pulled down and replaced by a more formal street plan with newer houses. The Piazza (first renamed Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II, then Piazza della Repubblica, the present name) was significantly widened and a large triumphal arch was constructed at the west end. This development was unpopular and was prevented from continuing by the efforts of several British and American people living in the city.[citation needed] A museum recording the destruction stands nearby today.

The country's second capital city was superseded by Rome six years later, after the withdrawal of the French troops allowed the capture of Rome.

20th century Porte Sante cemetery, burial place of notable figures of Florentine history

Porte Sante cemetery, burial place of notable figures of Florentine historyDuring World War II the city experienced a year-long German occupation (1943–1944) being part of the Italian Social Republic. Hitler declared it an open city on 3 July 1944 as troops of the British 8th Army closed in.[16] In early August, the retreating Germans decided to demolish all the bridges along the Arno linking the district of Oltrarno to the rest of the city, making it difficult for troops of the 8th Army to cross. However, at the last moment Charles Steinhauslin, at the time consul of 26 countries in Florence, convinced the German general in Italy that the Ponte Vecchio was not to be destroyed due to its historical value.[citation needed] Instead, an equally historic area of streets directly to the south of the bridge, including part of the Corridoio Vasariano, was destroyed using mines. Since then the bridges have been restored to their original forms using as many of the remaining materials as possible, but the buildings surrounding the Ponte Vecchio have been rebuilt in a style combining the old with modern design. Shortly before leaving Florence, as they knew that they would soon have to retreat, the Germans executed many freedom fighters and political opponents publicly, in streets and squares including the Piazza Santo Spirito.[citation needed]

1/5 Mahratta Light Infantry, Florence, 28 August 1944

1/5 Mahratta Light Infantry, Florence, 28 August 1944Florence was liberated by New Zealand, South African and British troops on 4 August 1944 alongside partisans from the Tuscan Committee of National Liberation (CTLN). The Allied soldiers who died driving the Germans from Tuscany are buried in cemeteries outside the city (Americans about nine kilometres or 5+1⁄2 miles south of the city, British and Commonwealth soldiers a few kilometres east of the centre on the right bank of the Arno).

At the end of World War II in May 1945, the US Army's Information and Educational Branch was ordered to establish an overseas university campus for demobilised American service men and women in Florence. The first American university for service personnel was established in June 1945 at the School of Aeronautics. Some 7,500 soldier-students were to pass through the university during its four one-month sessions (see G. I. American Universities).[17]

In November 1966, the Arno flooded parts of the centre, damaging many art treasures. Around the city there are tiny placards on the walls noting where the flood waters reached at their highest point.

^ Cite error: The named reference britannica.com was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ "History of Florence". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Retrieved 9 February 2023. ^ Hibbert, Christopher (1994). Florence: The Biography of a City. Penguin Books. p. 4. ISBN 0-14-016644-0. ^ "Cradle of capitalism". The Economist. 16 April 2009. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 16 October 2016. ^ defeated by Genoa in 1284 and subjugated by Florence in 1406 ^ Peters, Edward (1995). "The Shadowy, Violent Perimeter: Dante Enters Florentine Political Life". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society (113): 69–87. JSTOR 40166507. ^ Day, W.R. (3 January 2012). "The population of Florence before the Black Death: survey and synthesis". Journal of Medieval History. 28 (2): 93–129. doi:10.1016/S0304-4181(02)00002-7. S2CID 161168875. ^ "Decameron Web, Boccaccio, Plague". Brown University. ^ Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 184. ISBN 0-900658-15-0. ^ Pallanti, Giuseppe (2006). Mona Lisa Revealed: The True Identity of Leonardo's Model. Florence, Italy: Skira. pp. 17, 23, 24. ISBN 978-88-7624-659-3. ^ "Treccani - la cultura italiana | Treccani, il portale del sapere". ^ "History of Florence". Britannica.com. Retrieved 15 July 2021. ^ "Laurentian Library". michelangelo.net. Retrieved 15 July 2021. ^ Davis-Marks, Isis (2 June 2021). "Italian Art Restorers Used Bacteria to Clean Michelangelo Masterpieces". Smithsonian. Retrieved 15 July 2021. ^ Ryan, Billy (19 August 2020). "The Time When Jesus Was The King Of Florence". ucatholic.com. Retrieved 15 July 2021. ^ "July 3, 1944 newspaper archive". ^ "University Study Center, Florence « The GI University Project". Giuniversity.wordpress.com. 4 July 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- Stay safe

Florence is generally safe and healthy, but beware the inevitable purse-snatchers and pickpockets. They thrive in crowds, particularly around SMN railway station and on the buses, sometimes working with a decoy such as an insistent beggar. If you have a bag with a classy, noiseless zipper, it will be opened.

Also beware at night around tourist spots such as Ponte Vecchio where pickpocketers may approach you pretending to be drunk and friendly, and then snatch your belongings when your guard is down.