Tak'alik Ab'aj (; Mayan pronunciation: [takʼaˈlik aˀ'ɓaχ] ; Spanish: [takaˈlik aˈβax]) is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Guatemala. It was formerly known as Abaj Takalik; its ancient name may have been Kooja. It is one of several Mesoamerican sites with both Olmec and Maya features. The site flourished in the Preclassic and Classic periods, from the 9th century BC through to at least the 10th century AD, and was an important centre of commerce, trading with Kaminaljuyu and Chocolá. Investigations have revealed that it is one of the largest sites with sculptured monuments on the Pacific coastal plain. Olmec-style sculptures include a possible colossal head, petroglyphs and others. The site has one ...Read more

Tak'alik Ab'aj (; Mayan pronunciation: [takʼaˈlik aˀ'ɓaχ] ; Spanish: [takaˈlik aˈβax]) is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Guatemala. It was formerly known as Abaj Takalik; its ancient name may have been Kooja. It is one of several Mesoamerican sites with both Olmec and Maya features. The site flourished in the Preclassic and Classic periods, from the 9th century BC through to at least the 10th century AD, and was an important centre of commerce, trading with Kaminaljuyu and Chocolá. Investigations have revealed that it is one of the largest sites with sculptured monuments on the Pacific coastal plain. Olmec-style sculptures include a possible colossal head, petroglyphs and others. The site has one of the greatest concentrations of Olmec-style sculpture outside of the Gulf of Mexico, and was made a World Heritage Site in 2023 because of its long history of occupation.

Takalik Abaj is representative of the first blossoming of Maya culture that had occurred by about 400 BC. The site includes a Maya royal tomb and examples of Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions that are among the earliest from the Maya region. Excavation is continuing at the site; the monumental architecture and persistent tradition of sculpture in a variety of styles suggest the site was of some importance.

Finds from the site indicate contact with the distant metropolis of Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico and imply that Takalik Abaj was conquered by it or its allies. Takalik Abaj was linked to long-distance Maya trade routes that shifted over time but allowed the city to participate in a trade network that included the Guatemalan highlands and the Pacific coastal plain from Mexico to El Salvador.

Takalik Abaj was a sizeable city with the principal architecture clustered into four main groups spread across nine terraces. While some of these were natural features, others were artificial constructions requiring an enormous investment in labor and materials. The site featured a sophisticated water drainage system and a wealth of sculptured monuments.

The site had a long and continuous settlement history, with the period of principal occupation stretching from the Middle Preclassic down to the Postclassic. The earliest known occupation at Takalik Abaj dates towards the end of the Early Preclassic, ca. 1000 BC. However, it was not until the Middle to Late Preclassic that its first real florescence began with a noted surge in architectural constructions.[1] From this period onwards a continuity of culture and population settlement is in evidence, as represented by the persistence of a local ceramic style (called Ocosito) that remained in use until the Late Classic. The Ocosito style was typically made with red paste and pumice and extended westwards at least as far as Coatepeque, southwards to the Ocosito River and eastwards to the Samalá River. By the Terminal Classic, pottery associated with a highland Kʼicheʼ ceramic style had begun to appear intermixed with Ocosito ceramic complex deposits. Ocosito ceramics were replaced entirely by the Kʼicheʼ ceramic tradition by the Early Postclassic period.[2]

Approximate occupational timescale of Takalik Abaj Period Division Dates Summary Preclassic Early Preclassic 1000–800 BC Diffuse population Middle Preclassic 800–300 BC Olmec Late Preclassic 300 BC – AD 200 Early Maya Classic Early Classic AD 200–600 Teotihuacan-linked conquest Late Classic Late Classic AD 600–900 Local recovery Terminal Classic AD 800–900 Postclassic Early Postclassic AD 900–1200 Kʼicheʼ occupation Late Postclassic AD 1200–1524 Abandonment Note: The period spans used at Takalik Abaj differ slightly from those generally used in the standard chronology applied to the wider Mesoamerican region. Early PreclassicTakalik Abaj was first occupied at the end of the Early Preclassic period.[3] The remains of an Early Preclassic residential area have been found to the west of the Central Group, on the bank of the El Chorro stream. These first houses were built with floors made from river cobbles and reed-thatched roofs supported on timber poles.[4] Pollen analysis has revealed that the first inhabitants entered the area when it was still thick forest, which they began to clear in order to cultivate maize and other plants.[5] Over 150 pieces of obsidian have been recovered from this area, known as El Escondite, mostly originating from the San Martín Jilotepeque and El Chayal sources.[6]

Middle PreclassicTakalik Abaj was reoccupied at the beginning of the Middle Preclassic.[1] This was probably by Mixe–Zoquean inhabitants, as evidenced by the plentiful Olmec-style sculpture at the site dating to this period.[7][8] The construction of public architecture had probably begun by the Middle Preclassic;[9] the earliest structures were made of clay, which was sometimes partially burned in order to harden it.[1] Ceramics from this period belonged to the local Ocosito tradition.[9] This ceramic tradition, although it was local, showed strong affinities with the ceramics of the coastal plain and foothills of the Escuintla region.[8]

The Pink Structure (Estructura Rosada in Spanish) was built as a low platform during the first part of the Middle Preclassic, at a time when the city was producing Olmec-style sculpture and La Venta was flourishing on the Gulf coast of Mexico (c.800–700 BC).[10] During the latter part of the Middle Preclassic (c.700–400 BC), the Pink Structure was buried under the first version of the enormous Structure 7.[10] It was at this time that the use of Olmec ceremonial structures was discontinued and Olmec sculpture was destroyed, signalling an intermediate period prior to the beginning of the city's Early Maya phase.[10] The transition between the two phases was a gradual one, without abrupt changes.[11]

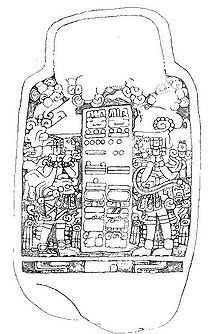

Late Preclassic Stela 5 from Takal'ik Ab'aj. The latest of the two Long Count dates is equivalent to a date in AD 126. The dates are flanked by rulers, probably symbolising the passing of power from one king to the next.[12] Click here for a photo of this stela.

Stela 5 from Takal'ik Ab'aj. The latest of the two Long Count dates is equivalent to a date in AD 126. The dates are flanked by rulers, probably symbolising the passing of power from one king to the next.[12] Click here for a photo of this stela.During the Late Preclassic (300 BC – AD 200) various sites in the Pacific coastal region developed into true cities; Takalik Abaj was one of these, with an area greater than 4 square kilometres (1.5 sq mi).[13] The cessation of Olmec influence upon the Pacific coastal zone occurred at the beginning of the Late Preclassic.[8] At this time Takalik Abaj emerged as an important centre with an apparently local style of art and architecture;[14] the inhabitants began to make boulder sculptures and to erect stelae and associated altars.[15] At this time, between 200 BC and 150 AD, Structure 7 reached its maximum dimensions.[10] Monuments were erected with both political and religious significance, some of which bore Maya-style dates and depictions of rulers.[16] These early Maya monuments are carved with what may be among the earliest Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions and use of the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar.[17] The early dates on Stelae 2 and 5 allow this style of sculpture to be more securely fixed in time within the late 1st century to the early 2nd century AD.[10] The so-called potbelly style of sculpture also appeared at this time.[17] The appearance of Maya sculpture and the cessation of Olmec-style sculpture may represent a Maya intrusion into the area previously occupied by Mixe–Zoquean inhabitants.[7][17] One possibility holds that Maya elites entered the area in order to take control of the cacao trade.[17] However, given the evident continuity in local ceramic styles from the Middle to Late Preclassic, the change in attributes from Olmec to Maya may have been more an ideological than a physical transition.[17] If they had arrived from elsewhere, the finds of Maya stelae and a Maya royal tomb suggest that the Maya were in a dominant position, whether they arrived as traders or conquerors.[18]

There is evidence of increasing contact with Kaminaljuyu, which emerged as a principal centre at this time, linking the Pacific coastal trade routes with the Motagua River route, as well as increased contact with other sites along the Pacific coast.[19] Within this extended trade route, Takalik Abaj and Kaminaljuyu appear to have been the two principal foci.[8] The early Maya style of sculpture spread throughout this network.[20]

During the Late Preclassic structures were built using volcanic stone held together with clay, as in the Middle Preclassic.[1] However, they evolved to include stepped structures with indented corners and stairways dressed with rounded pebbles.[20] At the same time, old Olmec-style sculptures were moved from their original positions and placed in front of the new-style buildings, sometimes reusing sculpture fragments in the stone facing.[10]

Although the Ocosito ceramic tradition continued in use,[20] the Late Preclassic ceramics in Takalik Abaj were strongly related to the Miraflores Ceramic Sphere that included Escuintla, the Valley of Guatemala and western El Salvador.[8] This ceramic tradition consists of fine red wares that are particularly associated with Kaminaljuyu and are found throughout the southeastern Guatemalan highlands and the adjacent Pacific slope.[21]

Early Classic Early Classic cylindrical polychrome vessel from Takalik Abaj

Early Classic cylindrical polychrome vessel from Takalik AbajIn the Early Classic, from around the 2nd century AD, the stela style that developed at Takalik Abaj and was associated with the portrayal of historic figures was adopted across the Maya lowlands, particularly in the Petén Basin.[22] During this period some of the pre-existing monuments were deliberately destroyed.[23]

In this period, the ceramics showed a change with the entry of the highland Solano style,[24] This ceramic tradition is most associated with the Solano site in the southeastern Valley of Guatemala and the most characteristic type is a brick-red ware covered with a bright orange micaceous slip, sometimes painted with pink or purple decoration.[25] This style of ceramics has been associated with the highland Kʼicheʼ Maya.[26] These new ceramics did not replace the pre-existing Ocosito complex but rather became mingled with them.[24]

Archaeological investigations have shown that the destruction of monuments and interruption of new construction at the site occurred simultaneously with the arrival of so-called Naranjo style ceramics, which appear to be linked to styles from the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico.[24] The Naranjo ceramic tradition is particularly characteristic of the western Pacific coast of Guatemala between the Suchiate and Nahualate rivers. The most common forms are pitchers and bowls with a surface that has been smoothed with a cloth, leaving parallel marks, and usually coated with a white or yellow wash.[27] At the same time, the use of local Ocosito ceramics waned. This Teotihuacan influence places the destruction of monuments in the second half of the Early Classic.[24] The presence of the conquerors linked to the Naranjo-style ceramics was not of long duration and suggests that the conquerors exerted long-distance control of the site, replacing the local rulers with their own governors while leaving the local population intact.[28]

The conquest of Takalik Abaj broke the ancient trade routes running along the Pacific coast from Mexico to El Salvador, these were replaced by a new route running up the Sierra Madre and into the northwestern Guatemalan highlands.[29]

Late Classic

In the Late Classic the site appears to have recovered from its earlier defeat. Naranjo-style ceramics diminished greatly in quantity and there was a surge in new large-scale construction. Many monuments broken by the conquerors were re-erected at this time.[31]

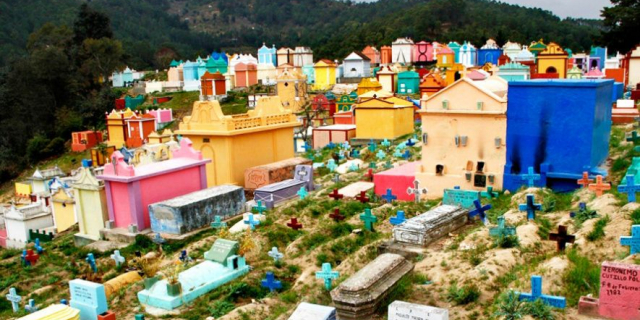

PostclassicAlthough use of the local Ocosito-style ceramics continued, there was a marked intrusion of Kʼicheʼ ceramics from the highlands in the Postclassic period, concentrated particularly in the northern part of the site but extending to cover the whole.[32] The indigenous accounts of the Kʼicheʼ themselves claim that they conquered this region of the Pacific coast, suggesting that the presence of their ceramics is associated with their conquest of Takalik Abaj.[31]

The Kʼicheʼ conquest appears to have taken place around AD 1000, some four centuries earlier than had been supposed using calculations based on the indigenous accounts.[33] After the initial arrival of the Kʼicheʼ activity continued at the site without pause, and the local styles were simply replaced by styles associated with the conquerors.[34] This suggests that the original inhabitants abandoned the city they had occupied for almost two millennia.[35]

Modern historyThe first published account appeared in 1888, written by Gustav Bruhl.[36] The German ethnologist and naturalist Karl Sapper described Stela 1 in 1894 after he saw it beside the road he was travelling.[36] Max Vollmberg, a German artist, drew Stela 1 and noted some other monuments, which attracted the interest of Walter Lehmann.[36]

In 1902 the eruption of the nearby Santiaguito volcano covered the site in a layer of volcanic ash that varies between 40 and 50 centimetres (16 and 20 in) thick.[37]

Walter Lehmann began the study of the sculptures of Takalik Abaj in the 1920s.[7] In January 1942 J. Eric S. Thompson visited the site with Ralph L. Roys and William Webb on behalf of the Carnegie Institution while undertaking a study of the Pacific Coast,[38] publishing his accounts in 1943.[7] Further investigations were undertaken by Suzanna Miles, Lee Parsons and Edwin M. Shook.[7] Miles bestowed the name Abaj Takalik to the site, which appeared in her contributed chapter in volume 2 of the Handbook of Middle American Indians published 1965. Previously it had been known by various names, including San Isidro Piedra Parada and Santa Margarita, after the names of the plantations in which the site lies, and also by the name of Colomba, a village to the north in the department of Quetzaltenango.[36]

Excavations at the site in the 1970s were sponsored by the University of California, Berkeley.[7] They began in 1976 and were undertaken by John A. Graham, Robert F. Heizer and Edwin M. Shook.[36] This first season uncovered 40 new monuments, including Stela 5, to add to the dozen or so already known.[36] Excavations by the University of California at Berkeley continued until 1981 and uncovered even more monuments in that time.[36] From 1987 excavations have been continued by the Guatemalan Instituto de Antropología e Historia (IDAEH) under the direction of Miguel Orrego and Christa Schieber, and new monuments continue to be uncovered.[7][36] The site has been declared a national park.[7]

In 2002 Takalik Abaj was entered on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative Lists, under the heading of "The Mayan-Olmecan Encounter".[39] It was officially designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023 under the name National Archaeological Park Tak’alik Ab’aj.[40] Some of the artifacts found at the site are on display at the National Museum of Guatemalan Art.[41][42]

Add new comment