Context of Cyprus

Cyprus ( (listen)), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It is geographically in Western Asia, but its cultural ties and geopolitics are overwhelmingly Southeastern European. Cyprus is the third-largest and third-most populous island in the Mediterranean. It is located north of Egypt, east of Greece, south of Turkey, and west of Lebanon and Syria. Its capital and largest city is Nicosia. The northeast portion of the island is de facto governed by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

The earliest known human activity on the island dates to around the 10th millennium BC. Archaeological remains include the well-preserved ruins from the Hellenistic period such as Salamis and Kourion, and Cyprus is home to some of the oldest water wells in the world. Cyprus ...Read more

Cyprus ( (listen)), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It is geographically in Western Asia, but its cultural ties and geopolitics are overwhelmingly Southeastern European. Cyprus is the third-largest and third-most populous island in the Mediterranean. It is located north of Egypt, east of Greece, south of Turkey, and west of Lebanon and Syria. Its capital and largest city is Nicosia. The northeast portion of the island is de facto governed by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

The earliest known human activity on the island dates to around the 10th millennium BC. Archaeological remains include the well-preserved ruins from the Hellenistic period such as Salamis and Kourion, and Cyprus is home to some of the oldest water wells in the world. Cyprus was settled by Mycenaean Greeks in two waves in the 2nd millennium BC. As a strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, it was subsequently occupied by several major powers, including the empires of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Persians, from whom the island was seized in 333 BC by Alexander the Great. Subsequent rule by Ptolemaic Egypt, the Classical and Eastern Roman Empire, Arab caliphates for a short period, the French Lusignan dynasty and the Venetians was followed by over three centuries of Ottoman rule between 1571 and 1878 (de jure until 1914).

Cyprus was placed under the United Kingdom's administration based on the Cyprus Convention in 1878 and was formally annexed by the UK in 1914. The future of the island became a matter of disagreement between the two prominent ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots, who made up 77% of the population in 1960, and Turkish Cypriots, who made up 18% of the population. From the 19th century onwards, the Greek Cypriot population pursued enosis, union with Greece, which became a Greek national policy in the 1950s. The Turkish Cypriot population initially advocated the continuation of the British rule, then demanded the annexation of the island to Turkey, and in the 1950s, together with Turkey, established a policy of taksim, the partition of Cyprus and the creation of a Turkish polity in the north.

Following nationalist violence in the 1950s, Cyprus was granted independence in 1960. The crisis of 1963–64 brought further intercommunal violence between the two communities, displaced more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots into enclaves: 56–59 and brought the end of Turkish Cypriot representation in the republic. On 15 July 1974, a coup d'état was staged by Greek Cypriot nationalists and elements of the Greek military junta in an attempt at enosis. This action precipitated the Turkish invasion of Cyprus on 20 July, which led to the capture of the present-day territory of Northern Cyprus and the displacement of over 150,000 Greek Cypriots and 50,000 Turkish Cypriots. A separate Turkish Cypriot state in the north was established by unilateral declaration in 1983; the move was widely condemned by the international community, with Turkey alone recognising the new state. These events and the resulting political situation are matters of a continuing dispute.

Cyprus is a major tourist destination in the Mediterranean. With an advanced, high-income economy and a very high Human Development Index, the Republic of Cyprus has been a member of the Commonwealth since 1961 and was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement until it joined the European Union on 1 May 2004. On 1 January 2008, the Republic of Cyprus joined the eurozone.

More about Cyprus

- Currency Euro

- Calling code +357

- Internet domain .cy

- Mains voltage 240V/50Hz

- Democracy index 7.56

- Population 1141166

- Area 9242

- Driving side left

- Prehistoric and Ancient Cyprus

Archaeological site of Khirokitia with early remains of human habitation during the Aceramic Neolithic period (reconstruction)

Archaeological site of Khirokitia with early remains of human habitation during the Aceramic Neolithic period (reconstruction)The earliest confirmed site of human activity on Cyprus is Aetokremnos, situated on the south coast, indicating that hunter-gatherers were active on the island from around 10,000 BC,[1] with settled village communities dating from 8200 BC....Read more

Read lessPrehistoric and Ancient Cyprus Archaeological site of Khirokitia with early remains of human habitation during the Aceramic Neolithic period (reconstruction)

Archaeological site of Khirokitia with early remains of human habitation during the Aceramic Neolithic period (reconstruction)The earliest confirmed site of human activity on Cyprus is Aetokremnos, situated on the south coast, indicating that hunter-gatherers were active on the island from around 10,000 BC,[1] with settled village communities dating from 8200 BC. The arrival of the first humans correlates with the extinction of the 75 cm high Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus and 1 metre tall Cyprus dwarf elephant, the only large mammals native to the island.[2] Water wells discovered by archaeologists in western Cyprus are believed to be among the oldest in the world, dated at 9,000 to 10,500 years old.[3]

Remains of an 8-month-old cat were discovered buried with a human body at a separate Neolithic site in Cyprus.[4] The grave is estimated to be 9,500 years old (7500 BC), predating ancient Egyptian civilisation and pushing back the earliest known feline-human association significantly.[5] The remarkably well-preserved Neolithic village of Khirokitia is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, dating to approximately 6800 BC.[6]

During the Late Bronze Age, the island experienced two waves of Greek settlement.[7] The first wave consisted of Mycenaean Greek traders, who started visiting Cyprus around 1400 BC.[8][9][10] A major wave of Greek settlement is believed to have taken place following the Late Bronze Age collapse of Mycenaean Greece from 1100 to 1050 BC, with the island's predominantly Greek character dating from this period.[10][11] The first recorded name of a Cypriot king is Kushmeshusha, as appears on letters sent to Ugarit in the 13th century BCE.[12] Cyprus occupies an important role in Greek mythology, being the birthplace of Aphrodite and Adonis, and home to King Cinyras, Teucer and Pygmalion.[13] Literary evidence suggests an early Phoenician presence at Kition, which was under Tyrian rule at the beginning of the 10th century BC.[14] Some Phoenician merchants who were believed to come from Tyre colonised the area and expanded the political influence of Kition. After c. 850 BC, the sanctuaries [at the Kathari site] were rebuilt and reused by the Phoenicians.

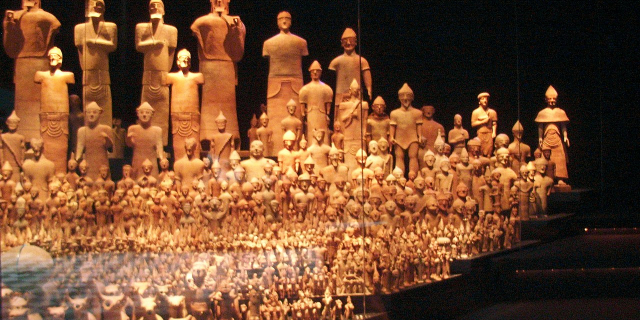

Zeus Keraunios, 500–480 BC, Nicosia museum

Zeus Keraunios, 500–480 BC, Nicosia museumCyprus is at a strategic location in the Middle East.[15][16][17] It was ruled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire for a century starting in 708 BC, before a brief spell under Egyptian rule and eventually Achaemenid rule in 545 BC.[10] The Cypriots, led by Onesilus, king of Salamis, joined their fellow Greeks in the Ionian cities during the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt in 499 BC against the Achaemenids. The revolt was suppressed, but Cyprus managed to maintain a high degree of autonomy and remained inclined towards the Greek world.[10] During the whole period of the Persian rule, there is a continuity in the reign of the Cypriot kings and during their rebellions they were crushed by Persian rulers from Asia Minor, which is an indication that the Cypriots were ruling the island with directly regulated relations with the Great King and there wasn't a Persian satrap.[18] The Kingdoms of Cyprus enjoyed special privileges and a semi-autonomous status, but they were still considered vassal subjects of the Great King.[18]

The island was conquered by Alexander the Great in 333 BC and Cypriot navy helped Alexander during the siege of Tyre (332 BC). Cypriot fleet were also sent to help Amphoterus.[19] In addition, Alexander had two Cypriot generals Stasander and Stasanor both from the Soli and later both became satraps in Alexander's empire. Following Alexander's death, the division of his empire, and the subsequent Wars of the Diadochi, Cyprus became part of the Hellenistic empire of Ptolemaic Egypt. It was during this period that the island was fully Hellenized. In 58 BC Cyprus was acquired by the Roman Republic.[10]

Roman Cyprus Middle Ages The Walls of Nicosia were built by the Venetians to defend the city in case of an Ottoman attack.

The Walls of Nicosia were built by the Venetians to defend the city in case of an Ottoman attack. Kyrenia Castle was originally built by the Byzantines and enlarged by the Venetians.

Kyrenia Castle was originally built by the Byzantines and enlarged by the Venetians.When the Roman Empire was divided into Eastern and Western parts in 286, Cyprus became part of the East Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire), and would remain so for some 900 years. Under Byzantine rule, the Greek orientation that had been prominent since antiquity developed the strong Hellenistic-Christian character that continues to be a hallmark of the Greek Cypriot community.[20]

Beginning in 649, Cyprus endured several attacks launched by raiders from the Levant, which continued for the next 300 years. Many were quick piratical raids, but others were large-scale attacks in which many Cypriots were slaughtered and great wealth carried off or destroyed.[20] There are no Byzantine churches which survive from this period; thousands of people were killed, and many cities – such as Salamis – were destroyed and never rebuilt.[10] Byzantine rule was restored in 965, when Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas scored decisive victories on land and sea.[10]

In 1156 Raynald of Châtillon and Thoros II of Armenia brutally sacked Cyprus over a period of three weeks, stealing so much plunder and capturing so many of the leading citizens and their families for ransom, that the island took generations to recover. Several Greek priests were mutilated and sent away to Constantinople.[21]

In 1185 Isaac Komnenos, a member of the Byzantine imperial family, took over Cyprus and declared it independent of the Empire. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Richard I of England captured the island from Isaac.[22] He used it as a major supply base that was relatively safe from the Saracens. A year later Richard sold the island to the Knights Templar, who, following a bloody revolt, in turn sold it to Guy of Lusignan. His brother and successor Aimery was recognised as King of Cyprus by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor.[10]

Following the death in 1473 of James II, the last Lusignan king, the Republic of Venice assumed control of the island, while the late king's Venetian widow, Queen Catherine Cornaro, reigned as figurehead. Venice formally annexed the Kingdom of Cyprus in 1489, following the abdication of Catherine.[10] The Venetians fortified Nicosia by building the Walls of Nicosia, and used it as an important commercial hub. Throughout Venetian rule, the Ottoman Empire frequently raided Cyprus. In 1539 the Ottomans destroyed Limassol and so fearing the worst, the Venetians also fortified Famagusta and Kyrenia.[10]

Although the Lusignan French aristocracy remained the dominant social class in Cyprus throughout the medieval period, the former assumption that Greeks were treated only as serfs on the island[10] is no longer considered by academics to be accurate. It is now accepted that the medieval period saw increasing numbers of Greek Cypriots elevated to the upper classes, a growing Greek middle ranks,[23] and the Lusignan royal household even marrying Greeks. This included King John II of Cyprus who married Helena Palaiologina.[24]

Cyprus under the Ottoman Empire Cypri insvla nova descript 1573, Ioannes á Deutecum f[ecit]. Map of Cyprus newly drawn by Johannes van Deutecom, 1573.

Cypri insvla nova descript 1573, Ioannes á Deutecum f[ecit]. Map of Cyprus newly drawn by Johannes van Deutecom, 1573.In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought the island under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance by the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces capturing Cyprus massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants.[25] The previous Latin elite were destroyed and the first significant demographic change since antiquity took place with the formation of a Muslim community.[26] Soldiers who fought in the conquest settled on the island and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought to the island from Anatolia.[27] This new community also included banished Anatolian tribes, "undesirable" persons and members of various "troublesome" Muslim sects, as well as a number of new converts on the island.[28]

Büyük Han, a caravanserai in Nicosia, is an example of the surviving Ottoman architecture in Cyprus.

Büyük Han, a caravanserai in Nicosia, is an example of the surviving Ottoman architecture in Cyprus.The Ottomans abolished the feudal system previously in place and applied the millet system to Cyprus, under which non-Muslim peoples were governed by their own religious authorities. In a reversal from the days of Latin rule, the head of the Church of Cyprus was invested as leader of the Greek Cypriot population and acted as mediator between Christian Greek Cypriots and the Ottoman authorities. This status ensured that the Church of Cyprus was in a position to end the constant encroachments of the Roman Catholic Church.[29] Ottoman rule of Cyprus was at times indifferent, at times oppressive, depending on the temperaments of the sultans and local officials, and the island began over 250 years of economic decline.[30]

The ratio of Muslims to Christians fluctuated throughout the period of Ottoman domination. In 1777–78, 47,000 Muslims constituted a majority over the island's 37,000 Christians.[31] By 1872, the population of the island had risen to 144,000, comprising 44,000 Muslims and 100,000 Christians.[32] The Muslim population included numerous crypto-Christians,[33] including the Linobambaki, a crypto-Catholic community that arose due to religious persecution of the Catholic community by the Ottoman authorities;[33][34] this community would assimilate into the Turkish Cypriot community during British rule.[35]

As soon as the Greek War of Independence broke out in 1821, several Greek Cypriots left for Greece to join the Greek forces. In response, the Ottoman governor of Cyprus arrested and executed 486 prominent Greek Cypriots, including the Archbishop of Cyprus, Kyprianos, and four other bishops.[36] In 1828, modern Greece's first president Ioannis Kapodistrias called for union of Cyprus with Greece, and numerous minor uprisings took place.[37] Reaction to Ottoman misrule led to uprisings by both Greek and Turkish Cypriots, although none were successful. After centuries of neglect by the Ottoman Empire, the poverty of most of the people and the ever-present tax collectors fuelled Greek nationalism, and by the 20th century the idea of enosis, or union, with newly independent Greece was firmly rooted among Greek Cypriots.[30]

Under Ottoman rule, numeracy, school enrolment and literacy rates were all low. They persisted some time after Ottoman rule ended, and then increased rapidly during the twentieth century.[38]

Cyprus under the British Empire Hoisting the British flag at Nicosia

Hoisting the British flag at NicosiaIn the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and the Congress of Berlin, Cyprus was leased to the British Empire which de facto took over its administration in 1878 (though, in terms of sovereignty, Cyprus remained a de jure Ottoman territory until 5 November 1914, together with Egypt and Sudan)[39] in exchange for guarantees that Britain would use the island as a base to protect the Ottoman Empire against possible Russian aggression.[10]

Greek Cypriot demonstrations for Enosis (union with Greece) in 1930

Greek Cypriot demonstrations for Enosis (union with Greece) in 1930The island would serve Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, when the Famagusta harbour was completed, Cyprus was a strategic naval outpost overlooking the Suez Canal, the crucial main route to India which was then Britain's most important overseas possession. Following the outbreak of the First World War and the decision of the Ottoman Empire to join the war on the side of the Central Powers, on 5 November 1914 the British Empire formally annexed Cyprus and declared the Ottoman Khedivate of Egypt and Sudan a Sultanate and British protectorate.[39][10]

In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Greece, ruled by King Constantine I of Greece, on condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British. The offer was declined. In 1923, under the Treaty of Lausanne, the nascent Turkish republic relinquished any claim to Cyprus,[40] and in 1925 it was declared a British crown colony.[10] During the Second World War, many Greek and Turkish Cypriots enlisted in the Cyprus Regiment.

The Greek Cypriot population, meanwhile, had become hopeful that the British administration would lead to enosis. The idea of enosis was historically part of the Megali Idea, a greater political ambition of a Greek state encompassing the territories with Greek inhabitants in the former Ottoman Empire, including Cyprus and Asia Minor with a capital in Constantinople, and was actively pursued by the Cypriot Orthodox Church, which had its members educated in Greece. These religious officials, together with Greek military officers and professionals, some of whom still pursued the Megali Idea, would later found the guerrilla organisation Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston or National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA).[41][42] The Greek Cypriots viewed the island as historically Greek and believed that union with Greece was a natural right.[43] In the 1950s, the pursuit of enosis became a part of the Greek national policy.[44]

A British soldier facing a crowd of Greek Cypriot demonstrators in Nicosia (1956)

A British soldier facing a crowd of Greek Cypriot demonstrators in Nicosia (1956)Initially, the Turkish Cypriots favoured the continuation of the British rule.[45] However, they were alarmed by the Greek Cypriot calls for enosis, as they saw the union of Crete with Greece, which led to the exodus of Cretan Turks, as a precedent to be avoided,[46][47] and they took a pro-partition stance in response to the militant activity of EOKA.[48] The Turkish Cypriots also viewed themselves as a distinct ethnic group of the island and believed in their having a separate right to self-determination from Greek Cypriots.[43] Meanwhile, in the 1950s, Turkish leader Menderes considered Cyprus an "extension of Anatolia", rejected the partition of Cyprus along ethnic lines and favoured the annexation of the whole island to Turkey. Nationalistic slogans centred on the idea that "Cyprus is Turkish" and the ruling party declared Cyprus to be a part of the Turkish homeland that was vital to its security. Upon realising that the fact that the Turkish Cypriot population was only 20% of the islanders made annexation unfeasible, the national policy was changed to favour partition. The slogan "Partition or Death" was frequently used in Turkish Cypriot and Turkish protests starting in the late 1950s and continuing throughout the 1960s. Although after the Zürich and London conferences Turkey seemed to accept the existence of the Cypriot state and to distance itself from its policy of favouring the partition of the island, the goal of the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot leaders remained that of creating an independent Turkish state in the northern part of the island.[49][50]

In January 1950, the Church of Cyprus organised a referendum under the supervision of clerics and with no Turkish Cypriot participation,[51] where 96% of the participating Greek Cypriots voted in favour of enosis,[52][53][54]: 9 The Greeks were 80.2% of the total island' s population at the time (census 1946). Restricted autonomy under a constitution was proposed by the British administration but eventually rejected. In 1955 the EOKA organisation was founded, seeking union with Greece through armed struggle. At the same time the Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT), calling for Taksim, or partition, was established by the Turkish Cypriots as a counterweight.[55] British officials also tolerated the creation of the Turkish underground organisation T.M.T. The Secretary of State for the Colonies in a letter dated 15 July 1958 had advised the Governor of Cyprus not to act against T.M.T despite its illegal actions so as not to harm British relations with the Turkish government.[50]

Independence and inter-communal violence

The first president of Cyprus, Makarios III (left) and the first vice-president of Cyprus, Fazıl Küçük (right).

The first president of Cyprus, Makarios III (left) and the first vice-president of Cyprus, Fazıl Küçük (right).Cyprus was placed under the United Kingdom's administration based on the Cyprus Convention in 1878 and was formally annexed by the UK in 1914. The future of the island became a matter of disagreement between the two prominent ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots, who made up 77% of the population in 1960, and Turkish Cypriots, who made up 18% of the population. From the 19th century onwards, the Greek Cypriot population pursued enosis, union with Greece, which became a Greek national policy in the 1950s.[56][57] The Turkish Cypriot population initially advocated the continuation of the British rule, then demanded the annexation of the island to Turkey, and in the 1950s, together with Turkey, established a policy of taksim, the partition of Cyprus and the creation of a Turkish polity in the north.[58]

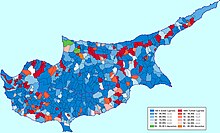

Ethnic map of Cyprus according to the 1960 census

Ethnic map of Cyprus according to the 1960 censusOn 16 August 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the Zürich and London Agreement between the United Kingdom, Greece and Turkey. Cyprus had a total population of 573,566; of whom 442,138 (77.1%) were Greeks, 104,320 (18.2%) Turks, and 27,108 (4.7%) others.[59] The UK retained the two Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, while government posts and public offices were allocated by ethnic quotas, giving the minority Turkish Cypriots a permanent veto, 30% in parliament and administration, and granting the three mother-states guarantor rights.

However, the division of power as foreseen by the constitution soon resulted in legal impasses and discontent on both sides, and nationalist militants started training again, with the military support of Greece and Turkey respectively. The Greek Cypriot leadership believed that the rights given to Turkish Cypriots under the 1960 constitution were too extensive and designed the Akritas plan, which was aimed at reforming the constitution in favour of Greek Cypriots, persuading the international community about the correctness of the changes and violently subjugating Turkish Cypriots in a few days should they not accept the plan.[60] Tensions were heightened when Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios III called for constitutional changes, which were rejected by Turkey[54]: 17–20 and opposed by Turkish Cypriots.[60]

Intercommunal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police. The violence resulted in the death of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots,[61] destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots. The crisis resulted in the end of the Turkish Cypriot involvement in the administration and their claiming that it had lost its legitimacy;[54]: 56–59 the nature of this event is still controversial. In some areas, Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from travelling and entering government buildings, while some Turkish Cypriots willingly withdrew due to the calls of the Turkish Cypriot administration.[62] Turkish Cypriots started living in enclaves. The republic's structure was changed, unilaterally, by Makarios, and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with the deployment of UNFICYP troops.[54]: 56–59

In 1964, Turkey threatened to invade Cyprus[63] in response to the continuing Cypriot intercommunal violence, but this was stopped by a strongly worded telegram from the US President Lyndon B. Johnson on 5 June, warning that the US would not stand beside Turkey in case of a consequential Soviet invasion of Turkish territory.[64] Meanwhile, by 1964, enosis was a Greek policy and would not be abandoned; Makarios and the Greek prime minister Georgios Papandreou agreed that enosis should be the ultimate aim and King Constantine wished Cyprus "a speedy union with the mother country". Greece dispatched 10,000 troops to Cyprus to counter a possible Turkish invasion.[65]

Following nationalist violence in the 1950s, Cyprus was granted independence in 1960.[66] The crisis of 1963–64 brought further intercommunal violence between the two communities, displaced more than 25,000 Turkish Cypriots into enclaves[54]: 56–59 [67] and brought the end of Turkish Cypriot representation in the republic. On 15 July 1974, a coup d'état was staged by Greek Cypriot nationalists[68][69] and elements of the Greek military junta[70] in an attempt at enosis. This action precipitated the Turkish invasion of Cyprus on 20 July,[71] which led to the capture of the present-day territory of Northern Cyprus and the displacement of over 150,000 Greek Cypriots[72][73] and 50,000 Turkish Cypriots.[74] A separate Turkish Cypriot state in the north was established by unilateral declaration in 1983; the move was widely condemned by the international community, with Turkey alone recognising the new state. These events and the resulting political situation are matters of a continuing dispute.

1974 coup d'état, invasion, and divisionVarosha (Maraş), a suburb of Famagusta, was abandoned when its inhabitants fled in 1974 and remains under Turkish military control.On 15 July 1974, the Greek military junta under Dimitrios Ioannides carried out a coup d'état in Cyprus, to unite the island with Greece.[75][76][77] The coup ousted president Makarios III and replaced him with pro-enosis nationalist Nikos Sampson.[78] In response to the coup,[a] five days later, on 20 July 1974, the Turkish army invaded the island, citing a right to intervene to restore the constitutional order from the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee. This justification has been rejected by the United Nations and the international community.[84]

The Turkish air force began bombing Greek positions in Cyprus, and hundreds of paratroopers were dropped in the area between Nicosia and Kyrenia, where well-armed Turkish Cypriot enclaves had been long-established; while off the Kyrenia coast, Turkish troop ships landed 6,000 men as well as tanks, trucks and armoured vehicles.[85][86]

Three days later, when a ceasefire had been agreed,[87] Turkey had landed 30,000 troops on the island and captured Kyrenia, the corridor linking Kyrenia to Nicosia, and the Turkish Cypriot quarter of Nicosia itself.[87] The junta in Athens, and then the Sampson regime in Cyprus fell from power. In Nicosia, Glafkos Clerides temporarily assumed the presidency.[87] But after the peace negotiations in Geneva, the Turkish government reinforced their Kyrenia bridgehead and started a second invasion on 14 August.[88] The invasion resulted in Morphou, Karpass, Famagusta and the Mesaoria coming under Turkish control.

International pressure led to a ceasefire, and by then 36% of the island had been taken over by the Turks and 180,000 Greek Cypriots had been evicted from their homes in the north.[89] At the same time, around 50,000 Turkish Cypriots were displaced to the north and settled in the properties of the displaced Greek Cypriots. Among a variety of sanctions against Turkey, in mid-1975 the US Congress imposed an arms embargo on Turkey for using US-supplied equipment during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974.[90] There were 1,534 Greek Cypriots[91] and 502 Turkish Cypriots[92] missing as a result of the fighting from 1963 to 1974.

The Republic of Cyprus has de jure sovereignty over the entire island, including its territorial waters and exclusive economic zone, with the exception of the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, which remain under the UK's control according to the London and Zürich Agreements. However, the Republic of Cyprus is de facto partitioned into two main parts: the area under the effective control of the Republic, located in the south and west and comprising about 59% of the island's area, and the north,[93] administered by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, covering about 36% of the island's area. Another nearly 4% of the island's area is covered by the UN buffer zone. The international community considers the northern part of the island to be territory of the Republic of Cyprus occupied by Turkish forces.[b] The occupation is viewed as illegal under international law and amounting to illegal occupation of EU territory since Cyprus became a member of the European Union.[99]

Post-division A map showing the division of Cyprus

A map showing the division of CyprusAfter the restoration of constitutional order and the return of Archbishop Makarios III to Cyprus in December 1974, Turkish troops remained, occupying the northeastern portion of the island. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriot parliament, led by the Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş, proclaimed the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is recognised only by Turkey.[100]

The events of the summer of 1974 dominate the politics on the island, as well as Greco-Turkish relations. Turkish settlers have been settled in the north with the encouragement of the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot states. The Republic of Cyprus considers their presence a violation of the Geneva Convention,[54]: 56–59 whilst many Turkish settlers have since severed their ties to Turkey and their second generation considers Cyprus to be their homeland.[101]

Foreign Ministers of the European Union countries in Limassol during Cyprus Presidency of the EU in 2012

Foreign Ministers of the European Union countries in Limassol during Cyprus Presidency of the EU in 2012The Turkish invasion, the ensuing occupation and the declaration of independence by the TRNC have been condemned by United Nations resolutions, which are reaffirmed by the Security Council every year.[102] Attempts to resolve the Cyprus dispute have continued. In 2004, the Annan Plan, drafted by the UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, was put to a referendum in both Northern Cyprus and the Cypriot Republic. 65% of Turkish Cypriots voted in support of the plan and 74% Greek Cypriots voted against the plan, claiming that it disproportionately favoured the Turkish side.[103] In total, 66.7% of the voters rejected the Annan Plan.

On 1 May 2004 Cyprus joined the European Union, together with nine other countries.[104] Cyprus was accepted into the EU as a whole, although the EU legislation is suspended in Northern Cyprus until a final settlement of the Cyprus problem.

Efforts have been made to enhance freedom of movement between the two sides. In April 2003, Northern Cyprus unilaterally eased border restrictions, permitting Cypriots to cross between the two sides for the first time in 30 years.[105] In March 2008, a wall that had stood for decades at the boundary between the Republic of Cyprus and the UN buffer zone was demolished.[106] The wall had cut across Ledra Street in the heart of Nicosia and was seen as a strong symbol of the island's 32-year division. On 3 April 2008, Ledra Street was reopened in the presence of Greek and Turkish Cypriot officials.[107] North and South relaunched reunification talks in 2015,[108] but these collapsed in 2017.[109]

The European Union issued a warning in February 2019 that Cyprus, an EU member, was selling EU passports to Russian oligarchs, saying it would allow organised crime syndicates to infiltrate the EU.[110] In 2020 leaked documents revealed a wider range of former and current officials from Afghanistan, China, Dubai, Lebanon, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine and Vietnam who bought a Cypriot citizenship prior to a change of the law in July 2019.[111][112] Cyprus and Turkey have been engaged in a dispute over the extent of their exclusive economic zones, ostensibly sparked by oil and gas exploration in the area.[113]

^ Mithen, S. After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20000 BC–5000 BC. Boston: Harvard University Press 2005, p. 97. [1] Archived 10 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ Stuart Swiny, ed. (2001). The Earliest Prehistory of Cyprus: From Colonization to Exploitation (PDF). Boston, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2016. ^ Cite error: The named reference autogenerated2 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Wade, Nicholas (29 June 2007). "Study Traces Cat's Ancestry to Middle East". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2012. ^ Walton, Marsha (9 April 2004). "Ancient burial looks like human and pet cat". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2007. ^ Simmons, A. H. Faunal extinction in an island society: pygmy hippopotamus hunters of Cyprus. New York: Springer 1999, p. 15. [2] Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Thomas, Carol G. and Conant, Craig: The Trojan War, pp. 121–122. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 0-313-32526-X, 9780313325267. ^ Andreas G. Orphanides, "Late Bronze Age Socio-Economic and Political Organization, and the Hellenization of Cyprus", Athens Journal of History, volume 3, number 1, 2017, pp. 7–20 ^ A.D. Lacy. Greek Pottery in the Bronze Age. Taylor & Francis. p. 168. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Library of Congress Country Studies. Cyprus". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009. ^ Thomas, Carol G. The Trojan War. Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group 2005. p. 64. [3] Archived 3 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ Eric H. Cline (22 September 2015). 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7449-1. ^ Stass Paraskos, The Mythology of Cyprus (London: Orage Press, 2016) p.1f ^ Hadjisavvas, Sophocles (2013). The Phoenician Period Necropolis of Kition, Volume I. Shelby White and Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications. p. 1. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2019. ^ Getzel M Cohen (1995). The Hellenistic Settlements in Europe, the Islands and Asia Minor. University of California Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-520-91408-7. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Charles Anthony Stewart (2008). Domes of Heaven: The Domed Basilicas of Cyprus. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-549-75556-2. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Michael Spilling; Jo-ann Spilling (2010). Cyprus. Marshall Cavendish. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7614-4855-6. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ a b ALEXANDER_THE_GREAT_AND_THE_KINGDOMS_OF_CYPRUS_A_RECONSIDERATION ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND THE KINGDOMS OF CYPRUS -- A RECONSIDERATION ^ Arrian, Anabasis, 3.6.3 ^ a b This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Keefe, Eugene K.; Solsten, Eric (1993). "Historical Setting". In Solsten, Eric (ed.). Cyprus: A Country Study (Fourth ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 10–12. ISBN 0-8444-0752-6. ^ Norwich, J. J. (1995) Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. London: Viking, p. 121 ^ Riddle, J.M. A History of the Middle Ages. Lanham, MD, USA: Rowman & Littlefield 2008. p. 326. [4] Archived 15 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ See James G. Schryver, 'Colonialism or Conviviencia in Frankish Cyprus?' in I.W. Zartman (ed.), Understanding Life in the Borderlands: Boundaries in Depth and in Motio (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010) pp. 133–159; see also Evangelia Skoufari "Cyprus during the 16th century: a Frankish kingdom, a Venetian colony, a multicultural society", in Joves pensant la Mediterrània – Mar de diàleg, no. 5 dir. Enric Olivé Serret, Tarragona, Publicacions de la Universitat Rovira y Virgili, Tarragona 2008, pp. 283–295. ^ Benjamin Arbel, David Jacoby, Intercultural Contacts in the Medieval Mediterranean, (London: Taylor and Francis, 1996) p. 45 ^ Eric Solsten, ed. (1991). "Cyprus: A Country Study". Countrystudies.us. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013. ^ Mallinson, William (30 June 2005). Cyprus: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8. ^ Orhonlu, Cengiz (2010), "The Ottoman Turks Settle in Cyprus", in Inalcık, Halil (ed.), The First International Congress of Cypriot Studies: Presentations of the Turkish Delegation, Institute for the Study of Turkish Culture, p. 99 ^ Jennings, Ronald (1993), Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640, New York University Press, p. 232, ISBN 978-0-8147-4181-8 ^ Mallinson, William. "Cyprus a Historical Overview (Chipre Una Visión Historica)" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus website (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2012. ^ a b Cyprus – Ottoman Rule Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Library of Congress ^ Hatay, Mete (2007), Is the Turkish Cypriot population shrinking? (PDF), International Peace Research Institute, p. 19, ISBN 978-82-7288-244-9, archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2015, retrieved 7 May 2015 ^ Osmanli Nufusu 1830–1914 by Kemal Karpat, ISBN 975-333-169-X and Die Völker des Osmanischen by Ritter zur Helle von Samo. ^ a b Ronald Jennings (1 August 1992). Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640. NYU Press. pp. 596–. ISBN 978-0-8147-4318-8. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Captain A. R. Savile (1878). Cyprus. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 130. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Chrysostomos Pericleous (2009). Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan. I.B.Tauris. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-85771-193-9. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2010). Historical dictionary of Cyprus ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Lanham, Md. [u.a.]: Scarecrow Press. pp. xxvii, 124. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. ^ William Mallinson; Bill Mallinson (2005). Cyprus: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8. ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0. ^ a b Cite error: The named reference Lausanne-Egypt-Sudan-Cyprus was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Xypolia, Ilia (2011). "'Cypriot Muslims among Ottomans, Turks and British". Bogazici Journal. 25 (2): 109–120. doi:10.21773/boun.25.2.6. ^ Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–5. ISBN 978-0-19-975716-9. They hoped that the transfer of administration would pave the way for the island to be united with Greece—an aspiration known as 'enosis.' At the time, these calls for enosis were not just limited to Cyprus. Instead, Cyprus was part of a wider political movement ... This overarching political ambition was known as the Megali Idea (Great Idea). ^ Lange, Matthew (2011). Educations in Ethnic Violence: Identity, Educational Bubbles, and Resource Mobilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-139-50544-4. ^ a b Diez, Thomas (2002). The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union. Manchester University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7190-6079-3. ^ Huth, Paul (2009). Standing Your Ground: Territorial Disputes and International Conflict. University of Michigan Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-472-02204-5. From early 1950s onward Greece has favored union with Cyprus through a policy of enosis ^ Papadakis, Yiannis; Peristianis, Nicos; Welz, Gisela (18 July 2006). Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-253-11191-3. ^ Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-230-39207-6. ^ Pericleous, Chrysostomos (2009). Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan. I.B. Tauris. pp. 135–6. ISBN 978-0-85771-193-9. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. Greek Cypriots engaged in a military campaign for enosis, union with Greece. Turkish Cypriots, in response, expressed their desire for taksim, partition of the island. ^ Behlul (Behlul) Ozkan (Ozkan) (26 June 2012). From the Abode of Islam to the Turkish Vatan: The Making of a National Homeland in Turkey. Yale University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-300-18351-1. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. In line with the nationalist rhetoric that "Cyprus is Turkish", Menderes predicated his declaration upon the geographic proximity between Cyprus and Anatolia, thereby defining "Cyprus as an extension of Anatolia". It was striking that Menderes rejected partitioning the island into two ethnic states, a position that would define Turkey's foreign policy regarding Cyprus after 1957 ^ a b G. Bellingeri; T. Kappler (2005). Cipro oggi. Casa editrice il Ponte. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-88-89465-07-3. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. The educational and political mobilisation between 1948–1958, aiming at raising Turkish national consciousness, resulted in the involving Turkey as motherland in the Cyprus Question. From then on, Turkey, would work hand in hand with the Turkish Cypriot leadership and the British government to oppose the Greek Cypriot demand for Enosis and realise the partition of Cyprus, which meanwhile became the national policy. ^ Grob-Fitzgibbon, Benjamin (2011). Imperial Endgame: Britain's Dirty Wars and the End of Empire. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-230-30038-5. ^ Dale C. Tatum (1 January 2002). Who Influenced Whom?: Lessons from the Cold War. University Press of America. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7618-2444-2. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013. ^ Kourvetaris, George A. (1999). Studies on modern Greek society and politics. East European Monographs. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-88033-432-7. ^ a b c d e f Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal aspects of the Cyprus problem: Annan Plan and EU accession. EMartinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-15223-6. ^ Caesar V. Mavratsas. "Politics, Social Memory, and Identity in Greek Cyprus since 1974". cyprus-conflict.net. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2007. ^ Faustmann, Hubert; Ker-Lindsay, James (2008). The Government and Politics of Cyprus. Peter Lang. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-03911-096-4. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780810862982. ^ Trimikliniotis, Nicos (2012). Beyond a Divided Cyprus: A State and Society in Transformation. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-137-10080-1. ^ Eric Solsten, ed. Cyprus: A Country Study Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. ^ a b Eric Solsten, ed. Cyprus: A Country Study Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. ^ Oberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 120: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis." ^ Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–6. ISBN 978-0-19-975716-9. ^ "1964: Guns fall silent in Cyprus". BBC News. 24 April 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009. ^ Jacob M. Landau (1979). Johnson's 1964 letter to Inonu and Greek lobbying of the White House. Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2014). Cyprus and International Peacemaking 1964–1986. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-136-67752-6. ^ Cyprus date of independence Archived 13 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine (click on Historical review) ^ "U.S. Library of Congress – Country Studies – Cyprus – Intercommunal Violence". Countrystudies.us. 21 December 1963. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2009. ^ Mallinson, William (2005). Cyprus: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8. ^ "website". BBC News. 4 October 2002. Archived from the original on 26 July 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2009. ^ Constantine Panos Danopoulos; Dhirendra K. Vajpeyi; Amir Bar-Or (2004). Civil-military Relations, Nation Building, and National Identity: Comparative Perspectives. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-275-97923-2. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Cite error: The named reference Benvenisti2012 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Barbara Rose Johnston, Susan Slyomovics. Waging War, Making Peace: Reparations and Human Rights (2009), American Anthropological Association Reparations Task Force, p. 211 Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Morelli, Vincent. Cyprus: Reunification Proving Elusive (2011), DIANE Publishing, p. 10 Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island (2000), Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 125 Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Papadakis, Yiannis (2003). "Nation, narrative and commemoration: political ritual in divided Cyprus". History and Anthropology. 14 (3): 253–270. doi:10.1080/0275720032000136642. S2CID 143231403. culminating in the 1974 coup aimed at the annexation of Cyprus to Greece ^ Atkin, Nicholas; Biddiss, Michael; Tallett, Frank (23 May 2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-4443-9072-8. ^ Journal of international law and practice, Volume 5. Detroit College of Law at Michigan State University. 1996. p. 204. ^ "Cyprus: Big Troubles over a Small Island". Time. 29 July 1974. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011. ^ Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-139-49617-9. Tensions escalated again in July 1974, following a coup d'état by Greek Cypriots favouring a union of Cyprus with Greece. In response to the coup, Turkey invaded Cyprus. ^ Bryant, Rebecca; Papadakis, Yiannis (2012). Cyprus and the Politics of Memory: History, Community and Conflict. I.B.Tauris. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-78076-107-7. In response to the coup, Turkey launched a military offensive in Cyprus that divided the island along the Green Line, which now splits the entire island. ^ Diez, Thomas (2002). The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union. Manchester University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7190-6079-3. Turkey did, however, act unilaterally in 1974, in response to a military coup in Cyprus instigated by the military junta ruling then in Greece with the apparent objective of annexing the island. ^ Ker-Lindsay, James; Faustmann, Hubert; Mullen, Fiona (2011). An Island in Europe: The EU and the Transformation of Cyprus. I.B. Tauris. p. 3. ISBN 9781848856783. Divided since 1974, when Turkish forces invaded in response to a Greek led coup, many observers felt that taking in the island would either be far too risky or far too problematic. ^ Mirbagheri, Faruk (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. On 20 July 1974, in response to the coup and justifying its action under the Treaty of Guarantee, Turkey landed forces in Kyrenia. ^ Gray, Christine (2008). International Law and the Use of Force. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-19-102162-6. ^ Taki Theodoracopulos (1 January 1978). The Greek Upheaval: Kings, Demagogues, and Bayonets. Caratzas Bros. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-89241-080-4. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Eric Solsten; Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). Cyprus, a country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8444-0752-4. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ a b c Brendan O'Malley; Ian Craig (25 June 2001). The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion. I.B. Tauris. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-0-85773-016-9. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015. ^ Sumantra Bose (30 June 2009). Contested Lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus, and Sri Lanka. Harvard University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-674-02856-2. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015. ^ U.S. Congressional Record, V. 147, Pt. 3, 8 March 2001 to 26 March 2001 [5] Archived 10 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ Turkey and the United States: The Arms Embargo Period. Praeger Publishers (5 August 1986). 1986. ISBN 978-0275921415. ^ "Over 100 missing identified so far". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007. ^ "Missing cause to get cash injection". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007. ^ "According to the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 550 and 541". United Nations. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009. ^ European Consortium for Church-State Research. Conference (2007). Churches and Other Religious Organisations as Legal Persons: Proceedings of the 17th Meeting of the European Consortium for Church and State Research, Höör (Sweden), 17–20 November 2005. Peeters Publishers. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-429-1858-0. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015. There is little data concerning recognition of the 'legal status' of religions in the occupied territories, since any acts of the 'Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus' are not recognized by either the Republic of Cyprus or the international community. ^ Quigley (6 September 2010). The Statehood of Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-139-49124-2. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. The international community found this declaration invalid, on the ground that Turkey had occupied territory belonging to Cyprus and that the putative state was therefore an infringement on Cypriot sovereignty. ^ Nathalie Tocci (January 2004). EU Accession Dynamics and Conflict Resolution: Catalysing Peace Or Consolidating Partition in Cyprus?. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7546-4310-4. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. The occupied territory included 70 percent of the island's economic potential with over 50 percent of the industrial ... In addition, since partition Turkey encouraged mainland immigration to northern Cyprus. ... The international community, excluding Turkey, condemned the unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) as a. ^ Dr Anders Wivel; Robert Steinmetz (28 March 2013). Small States in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4094-9958-9. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. To this day, it remains unrecognised by the international community, except by Turkey ^ Peter Neville (22 March 2013). Historical Dictionary of British Foreign Policy. Scarecrow Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8108-7371-1. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. Ecevit ordered the army to occupy the Turkish area on 20 July 1974. It became the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, but Britain, like the rest of the international community, except Turkey, refused to extend diplomatic recognition to the enclave. British efforts to secure Turkey's removal from its surrogate territory after 1974 failed. ^ James Ker-Lindsay; Hubert Faustmann; Fiona Mullen (15 May 2011). An Island in Europe: The EU and the Transformation of Cyprus. I.B.Tauris. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84885-678-3. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. Classified as illegal under international law, and now due to Cyprus' accession into the European Union is also an illegal occupation of EU territory. ^ Cite error: The named reference CIA2019 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 5. Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 460. ISBN 978-0195334029. ^ "Full list UN Resolutions on Cyprus". Un.int. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012. ^ Palley, Claire (18 May 2005). An International Relations Debacle: The UN Secretary-general's Mission of Good Offices in Cyprus 1999–2004. Hart Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-84113-578-6. ^ Stephanos Constantinides & Joseph Joseph, 'Cyprus and the European Union: Beyond Accession', Études helléniques/Hellenic Studies 11 (2), Autumn 2003 ^ "Emotion as Cyprus border opens". BBC News. 23 April 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016. ^ "Greek Cypriots dismantle barrier". BBC News. 9 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008. ^ Ledra Street crossing opens in Cyprus Archived 15 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press article published on International Herald Tribune Website, 3 April 2008 ^ Hadjicostis, Menelaos (11 May 2015). "UN envoy says Cyprus reunification talks to resume May 15". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015. ^ Smith, Helena (7 July 2017). "Cyprus reunification talks collapse amid angry scenes". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2021. ^ "Cyprus 'golden passports' bring Russians into the EU". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019. ^ "Exclusive: Cyprus sold passports to 'politically exposed persons'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 August 2020. ^ Rakopoulos, Theodoros; Fischer, Leandros (10 November 2020). "In Cyprus, the Golden Passports Scheme Shows Us How Capitalism and Corruption Go Hand in Hand". Jacobin. Retrieved 13 November 2020. ^ "Cyprus: EU 'appeasement' of Turkey in exploration row will go nowhere". Reuters. 17 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Keefe, Eugene K.; Solsten, Eric (1993). "Historical Setting". In Solsten, Eric (ed.). Cyprus: A Country Study (Fourth ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 10–12. ISBN 0-8444-0752-6. ^ Norwich, J. J. (1995) Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. London: Viking, p. 121 ^ Riddle, J.M. A History of the Middle Ages. Lanham, MD, USA: Rowman & Littlefield 2008. p. 326. [4] Archived 15 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ See James G. Schryver, 'Colonialism or Conviviencia in Frankish Cyprus?' in I.W. Zartman (ed.), Understanding Life in the Borderlands: Boundaries in Depth and in Motio (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010) pp. 133–159; see also Evangelia Skoufari "Cyprus during the 16th century: a Frankish kingdom, a Venetian colony, a multicultural society", in Joves pensant la Mediterrània – Mar de diàleg, no. 5 dir. Enric Olivé Serret, Tarragona, Publicacions de la Universitat Rovira y Virgili, Tarragona 2008, pp. 283–295. ^ Benjamin Arbel, David Jacoby, Intercultural Contacts in the Medieval Mediterranean, (London: Taylor and Francis, 1996) p. 45 ^ Eric Solsten, ed. (1991). "Cyprus: A Country Study". Countrystudies.us. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013. ^ Mallinson, William (30 June 2005). Cyprus: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8. ^ Orhonlu, Cengiz (2010), "The Ottoman Turks Settle in Cyprus", in Inalcık, Halil (ed.), The First International Congress of Cypriot Studies: Presentations of the Turkish Delegation, Institute for the Study of Turkish Culture, p. 99 ^ Jennings, Ronald (1993), Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640, New York University Press, p. 232, ISBN 978-0-8147-4181-8 ^ Mallinson, William. "Cyprus a Historical Overview (Chipre Una Visión Historica)" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus website (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2012. ^ a b Cyprus – Ottoman Rule Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Library of Congress ^ Hatay, Mete (2007), Is the Turkish Cypriot population shrinking? (PDF), International Peace Research Institute, p. 19, ISBN 978-82-7288-244-9, archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2015, retrieved 7 May 2015 ^ Osmanli Nufusu 1830–1914 by Kemal Karpat, ISBN 975-333-169-X and Die Völker des Osmanischen by Ritter zur Helle von Samo. ^ a b Ronald Jennings (1 August 1992). Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640. NYU Press. pp. 596–. ISBN 978-0-8147-4318-8. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Captain A. R. Savile (1878). Cyprus. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 130. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Chrysostomos Pericleous (2009). Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan. I.B.Tauris. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-85771-193-9. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2010). Historical dictionary of Cyprus ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Lanham, Md. [u.a.]: Scarecrow Press. pp. xxvii, 124. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. ^ William Mallinson; Bill Mallinson (2005). Cyprus: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8. ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0. ^ a b Cite error: The named reference Lausanne-Egypt-Sudan-Cyprus was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Xypolia, Ilia (2011). "'Cypriot Muslims among Ottomans, Turks and British". Bogazici Journal. 25 (2): 109–120. doi:10.21773/boun.25.2.6. ^ Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–5. ISBN 978-0-19-975716-9. They hoped that the transfer of administration would pave the way for the island to be united with Greece—an aspiration known as 'enosis.' At the time, these calls for enosis were not just limited to Cyprus. Instead, Cyprus was part of a wider political movement ... This overarching political ambition was known as the Megali Idea (Great Idea). ^ Lange, Matthew (2011). Educations in Ethnic Violence: Identity, Educational Bubbles, and Resource Mobilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-139-50544-4. ^ a b Diez, Thomas (2002). The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union. Manchester University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7190-6079-3. ^ Huth, Paul (2009). Standing Your Ground: Territorial Disputes and International Conflict. University of Michigan Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-472-02204-5. From early 1950s onward Greece has favored union with Cyprus through a policy of enosis ^ Papadakis, Yiannis; Peristianis, Nicos; Welz, Gisela (18 July 2006). Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-253-11191-3. ^ Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-230-39207-6. ^ Pericleous, Chrysostomos (2009). Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan. I.B. Tauris. pp. 135–6. ISBN 978-0-85771-193-9. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. Greek Cypriots engaged in a military campaign for enosis, union with Greece. Turkish Cypriots, in response, expressed their desire for taksim, partition of the island. ^ Behlul (Behlul) Ozkan (Ozkan) (26 June 2012). From the Abode of Islam to the Turkish Vatan: The Making of a National Homeland in Turkey. Yale University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-300-18351-1. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. In line with the nationalist rhetoric that "Cyprus is Turkish", Menderes predicated his declaration upon the geographic proximity between Cyprus and Anatolia, thereby defining "Cyprus as an extension of Anatolia". It was striking that Menderes rejected partitioning the island into two ethnic states, a position that would define Turkey's foreign policy regarding Cyprus after 1957 ^ a b G. Bellingeri; T. Kappler (2005). Cipro oggi. Casa editrice il Ponte. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-88-89465-07-3. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. The educational and political mobilisation between 1948–1958, aiming at raising Turkish national consciousness, resulted in the involving Turkey as motherland in the Cyprus Question. From then on, Turkey, would work hand in hand with the Turkish Cypriot leadership and the British government to oppose the Greek Cypriot demand for Enosis and realise the partition of Cyprus, which meanwhile became the national policy. ^ Grob-Fitzgibbon, Benjamin (2011). Imperial Endgame: Britain's Dirty Wars and the End of Empire. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-230-30038-5. ^ Dale C. Tatum (1 January 2002). Who Influenced Whom?: Lessons from the Cold War. University Press of America. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7618-2444-2. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013. ^ Kourvetaris, George A. (1999). Studies on modern Greek society and politics. East European Monographs. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-88033-432-7. ^ a b c d e f Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal aspects of the Cyprus problem: Annan Plan and EU accession. EMartinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-15223-6. ^ Caesar V. Mavratsas. "Politics, Social Memory, and Identity in Greek Cyprus since 1974". cyprus-conflict.net. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2007. ^ Faustmann, Hubert; Ker-Lindsay, James (2008). The Government and Politics of Cyprus. Peter Lang. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-03911-096-4. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780810862982. ^ Trimikliniotis, Nicos (2012). Beyond a Divided Cyprus: A State and Society in Transformation. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-137-10080-1. ^ Eric Solsten, ed. Cyprus: A Country Study Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. ^ a b Eric Solsten, ed. Cyprus: A Country Study Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991. ^ Oberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 120: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis." ^ Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–6. ISBN 978-0-19-975716-9. ^ "1964: Guns fall silent in Cyprus". BBC News. 24 April 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2009. ^ Jacob M. Landau (1979). Johnson's 1964 letter to Inonu and Greek lobbying of the White House. Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations. ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2014). Cyprus and International Peacemaking 1964–1986. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-136-67752-6. ^ Cyprus date of independence Archived 13 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine (click on Historical review) ^ "U.S. Library of Congress – Country Studies – Cyprus – Intercommunal Violence". Countrystudies.us. 21 December 1963. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2009. ^ Mallinson, William (2005). Cyprus: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8. ^ "website". BBC News. 4 October 2002. Archived from the original on 26 July 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2009. ^ Constantine Panos Danopoulos; Dhirendra K. Vajpeyi; Amir Bar-Or (2004). Civil-military Relations, Nation Building, and National Identity: Comparative Perspectives. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-275-97923-2. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Cite error: The named reference Benvenisti2012 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Barbara Rose Johnston, Susan Slyomovics. Waging War, Making Peace: Reparations and Human Rights (2009), American Anthropological Association Reparations Task Force, p. 211 Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Morelli, Vincent. Cyprus: Reunification Proving Elusive (2011), DIANE Publishing, p. 10 Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island (2000), Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 125 Archived 12 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine ^ Papadakis, Yiannis (2003). "Nation, narrative and commemoration: political ritual in divided Cyprus". History and Anthropology. 14 (3): 253–270. doi:10.1080/0275720032000136642. S2CID 143231403. culminating in the 1974 coup aimed at the annexation of Cyprus to Greece ^ Atkin, Nicholas; Biddiss, Michael; Tallett, Frank (23 May 2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-4443-9072-8. ^ Journal of international law and practice, Volume 5. Detroit College of Law at Michigan State University. 1996. p. 204. ^ "Cyprus: Big Troubles over a Small Island". Time. 29 July 1974. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011. ^ Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-139-49617-9. Tensions escalated again in July 1974, following a coup d'état by Greek Cypriots favouring a union of Cyprus with Greece. In response to the coup, Turkey invaded Cyprus. ^ Bryant, Rebecca; Papadakis, Yiannis (2012). Cyprus and the Politics of Memory: History, Community and Conflict. I.B.Tauris. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-78076-107-7. In response to the coup, Turkey launched a military offensive in Cyprus that divided the island along the Green Line, which now splits the entire island. ^ Diez, Thomas (2002). The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union. Manchester University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7190-6079-3. Turkey did, however, act unilaterally in 1974, in response to a military coup in Cyprus instigated by the military junta ruling then in Greece with the apparent objective of annexing the island. ^ Ker-Lindsay, James; Faustmann, Hubert; Mullen, Fiona (2011). An Island in Europe: The EU and the Transformation of Cyprus. I.B. Tauris. p. 3. ISBN 9781848856783. Divided since 1974, when Turkish forces invaded in response to a Greek led coup, many observers felt that taking in the island would either be far too risky or far too problematic. ^ Mirbagheri, Faruk (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8108-6298-2. On 20 July 1974, in response to the coup and justifying its action under the Treaty of Guarantee, Turkey landed forces in Kyrenia. ^ Gray, Christine (2008). International Law and the Use of Force. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-19-102162-6. ^ Taki Theodoracopulos (1 January 1978). The Greek Upheaval: Kings, Demagogues, and Bayonets. Caratzas Bros. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-89241-080-4. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ Eric Solsten; Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). Cyprus, a country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8444-0752-4. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. ^ a b c Brendan O'Malley; Ian Craig (25 June 2001). The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion. I.B. Tauris. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-0-85773-016-9. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015. ^ Sumantra Bose (30 June 2009). Contested Lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus, and Sri Lanka. Harvard University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-674-02856-2. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015. ^ U.S. Congressional Record, V. 147, Pt. 3, 8 March 2001 to 26 March 2001 [5] Archived 10 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine ^ Turkey and the United States: The Arms Embargo Period. Praeger Publishers (5 August 1986). 1986. ISBN 978-0275921415. ^ "Over 100 missing identified so far". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007. ^ "Missing cause to get cash injection". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007. ^ "According to the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 550 and 541". United Nations. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009. ^ European Consortium for Church-State Research. Conference (2007). Churches and Other Religious Organisations as Legal Persons: Proceedings of the 17th Meeting of the European Consortium for Church and State Research, Höör (Sweden), 17–20 November 2005. Peeters Publishers. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-429-1858-0. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015. There is little data concerning recognition of the 'legal status' of religions in the occupied territories, since any acts of the 'Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus' are not recognized by either the Republic of Cyprus or the international community. ^ Quigley (6 September 2010). The Statehood of Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-139-49124-2. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. The international community found this declaration invalid, on the ground that Turkey had occupied territory belonging to Cyprus and that the putative state was therefore an infringement on Cypriot sovereignty. ^ Nathalie Tocci (January 2004). EU Accession Dynamics and Conflict Resolution: Catalysing Peace Or Consolidating Partition in Cyprus?. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7546-4310-4. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. The occupied territory included 70 percent of the island's economic potential with over 50 percent of the industrial ... In addition, since partition Turkey encouraged mainland immigration to northern Cyprus. ... The international community, excluding Turkey, condemned the unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) as a. ^ Dr Anders Wivel; Robert Steinmetz (28 March 2013). Small States in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4094-9958-9. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. To this day, it remains unrecognised by the international community, except by Turkey ^ Peter Neville (22 March 2013). Historical Dictionary of British Foreign Policy. Scarecrow Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8108-7371-1. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. Ecevit ordered the army to occupy the Turkish area on 20 July 1974. It became the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, but Britain, like the rest of the international community, except Turkey, refused to extend diplomatic recognition to the enclave. British efforts to secure Turkey's removal from its surrogate territory after 1974 failed. ^ James Ker-Lindsay; Hubert Faustmann; Fiona Mullen (15 May 2011). An Island in Europe: The EU and the Transformation of Cyprus. I.B.Tauris. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84885-678-3. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015. Classified as illegal under international law, and now due to Cyprus' accession into the European Union is also an illegal occupation of EU territory. ^ Cite error: The named reference CIA2019 was invoked but never defined (see the help page). ^ Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 5. Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 460. ISBN 978-0195334029. ^ "Full list UN Resolutions on Cyprus". Un.int. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012. ^ Palley, Claire (18 May 2005). An International Relations Debacle: The UN Secretary-general's Mission of Good Offices in Cyprus 1999–2004. Hart Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-84113-578-6. ^ Stephanos Constantinides & Joseph Joseph, 'Cyprus and the European Union: Beyond Accession', Études helléniques/Hellenic Studies 11 (2), Autumn 2003 ^ "Emotion as Cyprus border opens". BBC News. 23 April 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016. ^ "Greek Cypriots dismantle barrier". BBC News. 9 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008. ^ Ledra Street crossing opens in Cyprus Archived 15 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press article published on International Herald Tribune Website, 3 April 2008 ^ Hadjicostis, Menelaos (11 May 2015). "UN envoy says Cyprus reunification talks to resume May 15". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015. ^ Smith, Helena (7 July 2017). "Cyprus reunification talks collapse amid angry scenes". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2021. ^ "Cyprus 'golden passports' bring Russians into the EU". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019. ^ "Exclusive: Cyprus sold passports to 'politically exposed persons'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 August 2020. ^ Rakopoulos, Theodoros; Fischer, Leandros (10 November 2020). "In Cyprus, the Golden Passports Scheme Shows Us How Capitalism and Corruption Go Hand in Hand". Jacobin. Retrieved 13 November 2020. ^ "Cyprus: EU 'appeasement' of Turkey in exploration row will go nowhere". Reuters. 17 August 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- Stay safeBar in Ayia Napa during daytime

Cyprus is a remarkably safe country, with very little violent crime. Cars and houses frequently go unlocked. That said however, it is wise to be careful when accepting drinks from strangers, especially in Ayia Napa, since there have been numerous occasions of muggings.

Note also that the numerous Cypriot "cabarets" are not what their name implies but rather brothels associated with organized crime.

The hunting season in Cyprus is from November till February. There are around 59,000 hunters with licences. On Sundays and Wednesdays you have to be careful when going for a walk in the countryside. Note that many hunters don't respect the areas where hunting is forbidden. Cypriot hunters are known to drink alcohol before and during hunting. Keep your dogs and children safe.